Introduction

The 52nd session of UN Commission on Narcotic Drugs (CND) ended on 20 March 2009 in Vienna. The experts who took part agreed on the future pillars of international drug control policy for the next decade. At the same time, they assessed the results and implementation of the agreements adopted at the 20th United Nations General Assembly Special Session on the drug problem (UNGASS) in 1998. The declaration of 2009 called for a significant reduction in the growing of opium and coca over the next 10 years. The goal was not achieved. Today, drug trafficking is the most lucrative branch of organised crime, and within in it cocaine yields the most profits. In 2007, according to UN estimates, in the Andean region approximately 180,000 hectares of coca were grown, and nearly 1,000 tons of pure cocaine were produced. Nearly 250 tonnes were exported to Europe that year. In 2006, in Spain alone, the authorities seized 50 tonnes of this drug. Twelve million Europeans have consumed cocaine at least once in their lifetime. In 2007, in Europe there were 3.5 million young and adolescent consumers. In Spain, 3% of the population regularly consumes cocaine. This group accounts for about 20% of all those in Europe who use the drug.

There is a new dimension to the cocaine trafficking bound for Europe, and this requires more attention. After a significant rise in recent years, it is now estimated that nearly 50 tonnes of cocaine pass through West Africa each year before reaching European soil; in other words, one fifth of the cocaine that makes its way into Europe. The fragile States of West Africa are not in a position to take on Latin American organised crime gangs, which are much stronger in terms of resources. The establishment of the illegal drug market in those weak States goes hand in hand with a rise in instability, growing levels of corruption, possible financing of non-governmental armed groups and high incidence of cocaine use.

Drug consumption follows the market laws of supply and demand: the higher the price of the drug, the lower the demand, and consumption drops. Cocaine’s price is high even though its production costs are very low. What keeps prices high are penalisation of trafficking in and consumption of drugs and the control of supply. This system poses high risks for those working in this illegal market, who make up for this through charging high prices. At the same time, the control regime involves frequent drug seizures, which makes the product more scarce and that also contributes to raising prices. Therefore, any intervention in the chain of creation of added value must be evaluated in terms of the impact it has on prices. Embracing this logic has imminent implications for drug control policy: all measures to control supply, be they repressive, penal or linked to development policy, must be evaluated in light of the effect they have on the final price of cocaine.

Cocaine’s production and marketing chain follows an exponential price curve: the further the cocaine is from the producing country in the commercial chain, the higher its market price will be. For instance, a kilo of high-purity cocaine has a street value of nearly €80,000 in Spain, and that is a conservative estimate. The same kilo in Colombia is worth about €1,200. However, the coca-growing farmer gets no more than €250 for the coca leaves needed to produce that kilo of the drug. Because of this exponential increase in value, potential situations of a shortage of coca leaves or cocaine in the Andean region would not have visible effects on the final price in Europe or on consumption levels. As far as controlling supply is concerned, it is better to intervene in the chain of creation of cocaine’s added value only when the price of the drug is high enough for the shortage to have an effect on that price –far from the producing countries and close to the final consumer–.

For traffickers, the risk of getting caught increases with the amount of levels of control they must dodge. This increase in risk is reflected in the price of the drug. At the international level, there tends to be intervention at each point in the chain of production, using both penal and legal tools as well as political ones and others based on development: control of chemical precursors, forced eradication of coca crops, alternative development measures and transit control. This Working Paper aims to analyse the intervention measures recently reaffirmed by the CND. Using drug prices as a starting point, we analyse the problem of drug trafficking and assess the efficiency of policies to control supply. But no drug control policy can be based solely on limiting supply. It must also feature measures to reduce demand. However, the goal of this study is to review European foreign policy tools involved in controlling supply, leaving aside domestic policy measures designed to cut demand, the efficiency of which is widely recognised in most countries of the EU.

Coca-growing and cocaine traffic to Europe

(2.1) Coca-growing in the Andean region

The three main coca-growing countries –Bolivia, Peru and Colombia– produced 994 tonnes of pure cocaine[1] in 2007, according to estimates by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). The 181,600 hectares used to grow coca leaves in those countries correspond to a surface area nearly three times the size of the city of Madrid. Total coca crops have been growing non-stop since 2003. In 2007, 27% more crops were planted than in 2003; in Bolivia the increase was 5% and in Peru it was 4%. However, the total area was 20% below the record posted in 2000 (Figure 1). Right now the main coca producer is Colombia, with nearly 100,000 hectares. In Peru, the country that was the main producer until 1997, 50,000 hectares are being used to grow coca and in Bolivia the figure is 30.000.[2] In Ecuador and Venezuela, only small patches of coca-growing land have been detected and they tend not to surpass 100 hectares.[3]

Figure 1. Coca growing in Bolivia, Colombia and Peru, 1997-2007 (hectares)

Even though the amount of land used to grow coca is smaller than the estimate for 2001, cocaine production is higher. This is because growing methods are more efficient, and the processes for extracting the drug and refining cocaine are more powerful. This has allowed for higher production even though Colombian growers, faced with campaigns of massive eradication of coca, are forced to move their crops around constantly, parcel them up or even use land that yields less.[4] Pressure to do away with coca is so great that today in Colombia coca is grown in 23 of the country’s 32 provinces, and in many of these there was not a coca-growing tradition. As in many other regions where organic drugs are grown, in Colombia coca-growing is concentrated in areas of conflict or post-conflict, where sovereignty and the State’s territorial control are limited or non-existent. The Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), recidivist paramilitary groups, new armed groups (or emerging gangs)[5] and an endless number of criminal organisations large and small take part in the production chain. Each actor tries to obtain part of the value added, either by oversight of the crops, through direct control of production or by taking part in the internal or overseas trafficking of cocaine. In Peru, for a long time the coca-growing areas were also the areas where the Shining Path rebel group was active; it is now re-emerging as a narco-guerrilla organisation.[6] As in Peru and Bolivia the law allows the growing of coca up to a certain amount, there is not the same close relationship between armed groups, organised crime and coca farming as exists in Colombia.

Given the semi-legal status of coca-growing in Bolivia and Peru and the lack of massive eradication campaigns, the growing of it in those countries has not proliferated as much as it has in Colombia and is concentrated in certain regions.[7] Legal growing meets the demand for the coca used for traditional purposes –chewing it, making coca-leaf tea, medicinal purposes and rituals– which, unlike in Colombia, are widespread in Bolivia and Peru. In January 2009, the government of Evo Morales literally incorporated the phrase ‘Coca yes, Cocaine no’ into the country’s new constitution.[8] As coca-growing is partially legal in Bolivia and Peru, but the areas used for this are not easy to detect or control, it is practically inevitable that surplus crops are diverted to producing cocaine. Despite legal problems, Morales recently announced he would increase the amount of coca that can be grown legally in his country. Alluding to the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs of 1961, the fundamental charter of international drug control efforts, which bans the growing and consumption of coca leaves, the International Narcotics Control Board (INCB) tends to criticise the government of Bolivia vehemently over this policy.[9] In an impassioned speech on 11 March 2009, President Morales sought to persuade the members of the CND and the international community to remove coca leaves from the list of narcotics declared illegal by the Single Convention and to depenalise it.[10]

The EU, acknowledging the legitimacy of coca growing for medicinal and traditional uses, has been considering for years now the possibility of carrying out a study of legal demand for coca in Bolivia. The idea of such a study is to define how many hectares are needed to meet demand for legitimate purposes, thus avoiding excess production for illegal uses. But no such project has been devised so far, perhaps because the Bolivian government has no interest in its being carried out.

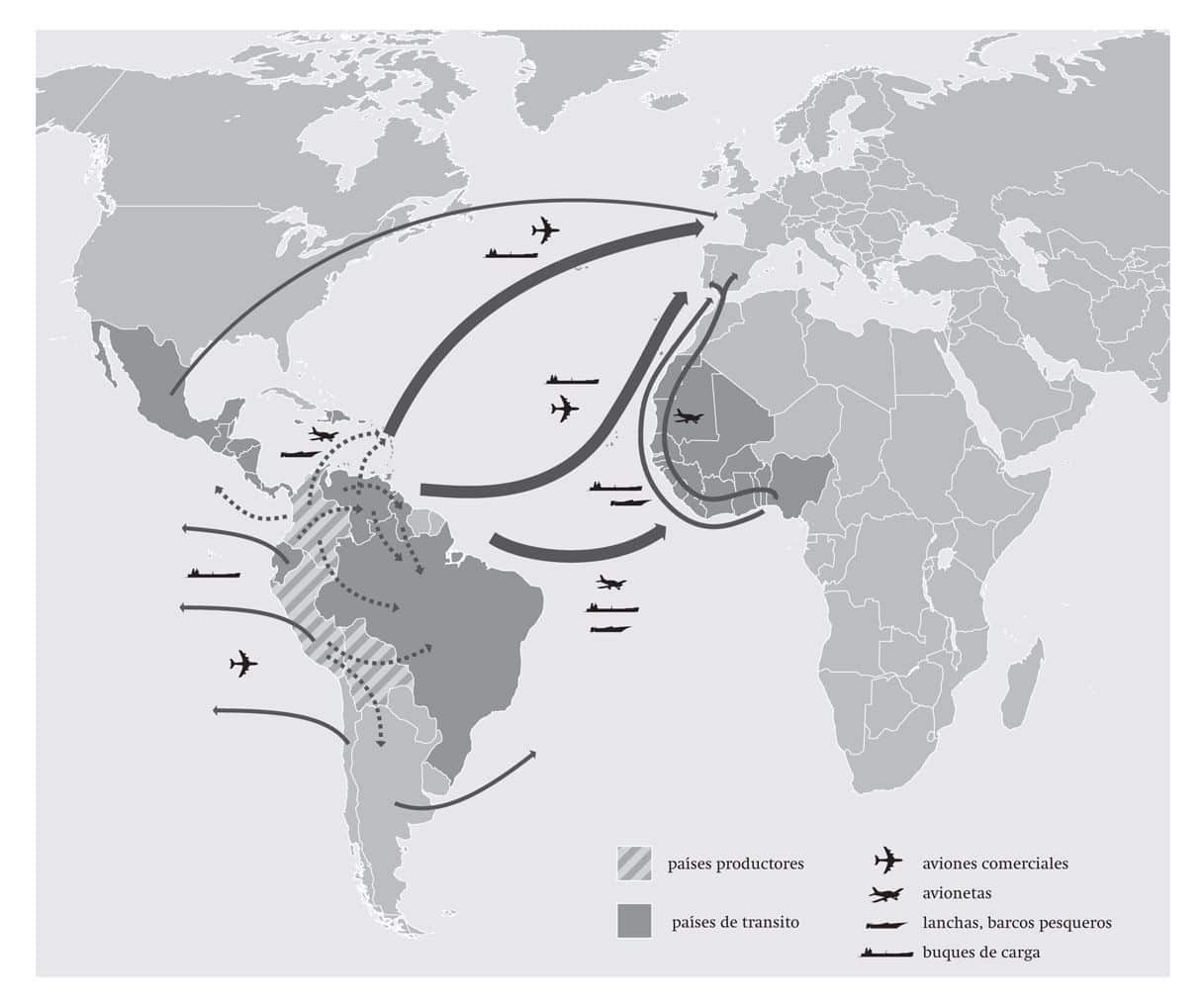

(2.2) Cocaine-trafficking routes

How is cocaine reaching Europe from the Andean region? In 2007, 121 tonnes of cocaine were seized in Europe in a total of 72,700 raids. Aside from air routes, EUROPOL has identified three main maritime paths for sending cocaine to Europe, within which there are many variations and modes of transport. All of them lead to the Iberian Peninsula, or at least pass through it:

- The northern route: Caribbean-Azores-Portugal/Spain.

- The middle route: South America-Cape Verde Islands/Madeira/Canary Islands-Western Europe.

- The African route: South America-West Africa-Portugal/Spain.

In the first two, the northern and middle routes, when the cocaine reaches the Atlantic archipelagos (the Canary Islands or the Azores, for instance) in it usually transferred to fishing vessels or speed boats for shipment to the European continent. Increasingly, the final transit countries for the cocaine before it reaches Europe are Venezuela and Brazil, followed by Argentina, Ecuador, Suriname and the former colonies and overseas territories of France, the UK and the Netherlands. Other countries of the Caribbean, and, more and more, Mexico, are also cited as stopover countries for South American cocaine bound for Europe.[11]

In recent years, Venezuela has become a major staging ground for cocaine trafficking from Colombia. From Venezuela the drug is distributed, supplying the US and European markets. As the government of President Hugo Chávez has refused to undertake greater levels of cooperation with US anti-drug agencies and legal institutions –it does not extradite people to the US– Venezuela has become a relatively safe haven for Colombian traffickers.[12] Compared to Colombia, Venezuela offers big advantages for cocaine traffickers, thanks to corrupt security forces, a highly permeable and practically uncontrollable jungle border spanning more than 2,000 km, and patchy efforts at crime-fighting. Cocaine is shipped from Venezuela in speedboats and ‘semi-submersible’ vessels to the Lesser Antilles and from there to the US and European markets. An ever-growing amount is shipped directly from Venezuela to West Africa.[13]

Brazil shares with the three main coca-producing countries 7,000 km of border in the Amazon basin, which, because of its topography and vegetation, makes effective control of drug trafficking more difficult.[14] Drug-trafficking rings take advantage of the porous nature of the Amazon region and ship cocaine to Brazil along rivers that are traditional routes for contraband. In this way they dodge stricter controls that are in place at ports and airports in the three coca-producing countries.

Map 1. The main routes for Europe-bound cocaine trafficking

The wholesale cocaine trade with Europe is dominated mainly by Colombian organisations that generally work with Spanish distribution networks, although lately they do it more often with Nigerian and Moroccan gangs.[15] Colombian traffickers have shown little interest in the retail trade and street-level dealing. Although in Spain Colombians are frequently identified as drug peddlers, one can assume they have little to do with the wholesale networks operating out of South America.[16]

(2.3) Entry points

The main entry points include Spain, Portugal and the Netherlands, although Germany, Belgium, France and the UK also serve this purpose.[17] EUROPOL distinguishes between two main entry and redistribution points: the north-western and south-western regions. The south-west region, featuring Spain, Portugal and the Atlantic archipelagos, are the main point of arrival for Andean cocaine. The Iberian Peninsula is an ideal entry and redistribution point because of abundant trade links with the cocaine-producing region and transit countries, an historical affinity with former Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking colonies, large and well-established networks of emigrants, closeness to Africa and extensive coastlines. The north-west region, which includes the north of France, Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands and the UK, is the second most important conduit for cocaine arrivals. The factors that lure organised criminals there are highly developed infrastructure, close relations and numerous links with certain transit countries, the largest ports and airports in all of Europe, access to trans-European corridors, and also emigrant colonies.

Other, smaller amounts of cocaine are brought in regularly by ‘mules’[18]travelling on airlines from all the countries of South America to Europe. The US State Department considers all the countries of the region to be transit nations, with the exception of Uruguay.[19] These so-called ‘mules’ swallow cocaine in small packets and transport it inside their digestive tract, or conceal it in their clothes or their luggage. Frequent points of departure for these human couriers are the former colonies and overseas territories of France, the UK and the Netherlands in the Caribbean, and French and British Guyana. Lately, Mexico –generally cited as a staging ground for drug trafficking to the US– is emerging more and more as a point of departure for ‘mules’ bound for Europe.[20] A direct air courier route has also been identified running from Brazil to West Africa. [21] For some time the authorities in the Netherlands reacted to the increase in drug trafficking on planes by imposing a policy of 100% control at Schiphol airport in Amsterdam. That meant that the authorities checked every passenger on flights from countries considered to be high-risk for cocaine trafficking (the Dutch Antilles, Suriname and Venezuela). These inspections, which have since been reduced, landed an average of 175 arrests per month in 2005.

The route of weakest governance: cocaine trafficking shifts to West Africa

(3.1) The magnitude of the shift

‘West Africa is under attack from Latin American drug traffickers’:[22] Antonio María Costa, secretary general of the UNODC, tends to use strong words to draw attention to the sharp rise in the cocaine business in West Africa. In 2008, a report from the secretary general of the UN called on the Security Council to consider taking sanctions against Guinea-Bissau to force the small coastal country to fight harder against cocaine trafficking in its territory and maritime zones.[23] Since 2005 more evidence has emerged that Colombian and Venezuelan gangs were setting up shop in West Africa as a safe haven, turning the region into a beachhead for shipping cocaine to Europe. There are many reasons that explain why the drug business is taking root in the region. In general, a mix of push and pull factors are at play: growing demand for cocaine in EU countries, tighter controls on traditional direct routes between South America and Europe, a declining cocaine market in the US and excellent conditions for setting up markets and undertaking illegal activities in West Africa.[24] For the UE, the establishment of drug trafficking ante portas posed a major challenge for EU security and public health. If a cocaine emporium is established on Europe’s outskirts, one can expect not only growing demand for cocaine but also the emergence or worsening of a series of secondary factors that can become serious security problems for the EU and its member countries. Whereas until recently the authorities in Africa did not tend to seize even one tonne of cocaine a year, in the period 2005-08 alone they confiscated 48 tonnes in Western Africa. (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Cocaine seizures in central and western Europe and in central and western Africa, 2001-06 (tonnes)

Given the shortfalls in the security forces and rule of law in that region, which is home to some of the world’s poorest countries, the amount of cocaine that is seized is not as representative as in other parts of the globe. One can presume that the real amount of cocaine that is trafficked in the region is a multiple of the volume that is actually seized. The UNODC’s conservative estimate is that every year nearly 50 tonnes of the drug move through West Africa; in other words, one-fifth of the cocaine bound for Europe goes through the region. That is more or less a quarter of the wholesale trade, is worth about US$450 million and ends up in the hands of African middlemen and helpers.[25]

There is some evidence that in particular Ghana, Guinea-Bissau (which has earned a reputation as Africa’s first narco-state), Guinea, Cape Verde and Senegal have become staging grounds for the largest flows of cocaine headed for Europe. However, the true magnitude of drug trafficking in other countries in the region cannot yet be ascertained, because of the lack of verifiable information on illegal activities and high levels of corruption associated with such activities.[26] The region’s geographical location, with countless uninhabited islands, un-monitored coastlines and thick vegetation, offer a wide range of potential trafficking routes. Drug trafficking-related activities have been reported in most countries, although lately it is happening most frequently in Sierra Leone, Benin and Togo.[27] There has been a significant increase recently in investments by South Americans in some countries of West Africa, such as purchases of real estate or fish- or wood-processing plants. One might assume that the acquisition of this property, possibly designed to mask illegal activities, points to the establishment of lasting structures in the region. This would allow for expansion of drug trafficking in the future.[28]

(3.2) Division of labour in transatlantic drug-trafficking

It is not easy to analyse how the division of labour works between South Americans, Europeans and Africans, due to scant reliable information. However, according to international drug control agencies, one can discern two different procedures. In the first of these, African middlemen are paid –similar to the interaction between Colombian drug cartels and Mexican associates in the 1980s and 90s– in small amounts of cocaine for their transport, merchandise-delivery and transfer services. These small amounts of what one might call ‘cocaine currency’ tend to be sent to Europe, either through human couriers travelling on commercial flights or through the mail.[29] Most of the African ‘mules’ arrested in European airports come from Guinea, Nigeria, Mali and Senegal. More than half of the airborne drug traffickers are of Nigerian origin, even on flights that do not originate in Nigeria.[30] Nigerian gangs often control street-level drug dealing in Europe. In France, most of the foreigners arrested for offenses related to drug trafficking are Nigerian. Compared to other ethnic groups, they stand out because of their flexibility and strong ties among members of their ethnic groups. ‘Mules’ are not normally members of criminal gangs, but rather used by organised traffickers as a ‘means of transport’ in the literal sense: they are loaded up at their point of departure and unloaded when they arrive at their destination.

In the second procedure, which involves wholesale trafficking, large cargos of cocaine from South America are transferred on the high seas to fishing vessels or speedboats, which have an African crew generally accompanied by a South American supervisor. They take the drugs to a temporary storage facility on the African continent. There, the cocaine is repackaged and sent to Europe aboard yachts, freighters, again fishing vessels or speed boats, mainly to Galicia and the northern coast of Portugal.[31] The Spanish and Portuguese authorities seized 69% of all the cocaine confiscated in Europe in 2006. Whereas Colombian groups have been all but overtaken by Mexican competitors in trafficking to the US, it is Colombians and also Venezuelans that dominate wholesale cocaine trafficking to Africa. The governments of Brazil and Colombia recently sent police and investigative units to West Africa, hoping for an improvement in cooperation between security and legal authorities in the two regions.[32] A rise in seizures by the Portuguese coast guard seems to suggest the formation of a trafficking route that starts off from Brazil, goes through Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde and ends up in Portugal.[33]

It is possible that ships carrying containers are also used to camouflage cocaine. As part of a series of spot checks during one month in 2007, evidence was gathered from 50 containers carrying wood from South America to West Africa. For two regions with abundant cheap wood, these amounts could generate suspicion and doubt, not just among government security forces –it seems obvious that wood is used as a cheap cover for concealing cocaine–. At the same time, every month thousands of containers are shipped from West Africa to north-western Europe, and many are registered as empty and thus not closely monitored. Aside from maritime traffic, South American drug traffickers use small planes or light aircraft that are re-fitted to endure transatlantic flights that start in Colombia, Brazil, Venezuela or Suriname and end up in illegal airstrips in West Africa.[34] But the spot where the cocaine-laden planes land in West Africa is not always clear, as it is just a moving point for the transfer of the drugs for later maritime shipment. There is some evidence that smaller amounts of cocaine are moved through the interior of coastal states to neighbouring countries, often those which have direct, regular flights to European capitals. There have also been cases, probably rare ones, in which drugs were shipped from the beaches of the Gulf of Guinea over land to Morocco and from there to Europe, following the classic routes for sneaking in marijuana and contraband. For this reason the capital of Mali, Bamako, has been cited as a major transit point for South American cocaine even though the city is 1,000 km from the coast.[35]

(3.3) Weak governance as a lure

Aside from Nigeria, Ghana and Senegal, probably no State in West Africa is capable of confronting successfully and on its own the organised crime gangs that are settling on their territory. One hundred kilos of pure cocaine, dumped on a beach in Guinea-Bissau, would have a market value in Europe that is equivalent to all the development aid that the country receives in a year. Several hundred kilos of cocaine allegedly arrive weekly to Guinea-Bissau.[36] The US$450 million in drug profits that UNODC estimates stay in the hands of African intermediaries each year are equal to all the foreign direct investment made in Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Mali and Senegal in 2005.[37] Barring three countries, all the members of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) are among the least developed countries of the world, according to the United Nations’ ranking. And five of them are the world’s least developed countries.[38]

The fragile or failed States of West Africa conduct in a very limited fashion the functions of governance in the areas of security, social policy and legitimacy/rule of law.[39] Their exercise of the monopoly on legitimate use of force against organised crime and in controlling the country’s territory is deficient at best. As an example illustrating the consequences of the decay of a State and its governance functions in the area of security, it is often noted that these days Guinea-Bissau has no jail on its territory. In West Africa, cocaine trafficking rings find ideal conditions. It is a perfect geographical prolongation of the coca-producing countries; weak state structures are the norm, with limited territorial control and legal systems with limited scope. Both regions offer certain ‘comparative advantages’[40] for criminal elements, which encourages the establishment of trans-national black markets and easy creation of illegal added-value. Due to growing pressure from government anti-drug agencies along traditional smuggling routes, West Africa attracts people involved in the cocaine trade because of the favourable operating conditions it offers. The result of this is a rise in organised crime activities in the region. As the drug trade takes root, consumption of drugs also increases. This has been observed in many transit countries, where higher demand is fuelled by more abundant supply. This happens in Central America and Brazil, but also in Guinea-Bissau. In many cases the rise in consumption stems from the distribution of ‘cocaine currency’.[41] Besides this, along with drug trafficking what is also expanding is a series of secondary effects such as corruption, violence, money laundering, and trafficking in light and small weapons. The most visible example of this effect has been observed in Mexico, where the conflict with and among drug cartels claimed more than 6,000 lives in 2008, according to official figures.[42]

In the drug trade, violence plays the same role that trade legislation and arbitration bodies perform in markets that are legal. The absence of these institutions in illegal sectors leads to pockets of self-regulation by criminals in the illegal market. According to some estimates, more than 80% of drug-related violent acts stem from the resolution of economic conflicts or criminal elements competing for leadership. Contrary to what one might presume, only a small percentage of drug-related violence stems from people being high on drugs or crimes involving people seeking money to buy them.[43] In West Africa, all it takes is a moderate bribe to neutralise the already weak control that authorities have on their territory, or the police. There have been rumours of bribes being paid to Cabinet members and senior military officials with money from drug trafficking in some countries of the region, and it comes as no surprise that this has been linked mainly to Guinea-Bissau.[44] The establishment of trans-national black markets is accentuating the region’s development problems and encouraging a tendency toward illegal activities within these societies.[45]

Aside from simple bribes paid with money from drug trafficking, there are security concerns that go beyond corruption. The UNODC and security forces in several European countries worry about links developing between cocaine traffickers and certain political movements or insurgent groups. The fear is that such groups could take in large amounts of money with drug trafficking. There is ample evidence that drug money was used in coups which were carried out or attempted in August and December of 2008 in Guinea-Bissau and Guinea. The cocaine trade has also been linked to growing political violence in Guinea-Bissau in 2009, including the assassinations of President Vieira and the commander-in-chief of the armed forces in March, and of several ex-ministers and a presidential candidate in June.[46] The fear is that drug money could be used to finance more corps, prop up pliant politicians or prolong armed conflicts that have been simmering for years in some countries of West Africa. Along the Sahel belt, an area of limited if not totally absent governability, there is concern over possible collaboration between Tuareg rebels, the North African branch of al-Qaeda and drug traffickers. Were a cocaine-trafficking conduit running from West Africa toward Libya and Egypt to be established along traditional routes for smuggling marijuana, terrorists operating in the region could reap huge profits. This is a recurring worry for the US Government.[47]

The rise in cocaine consumption in Europe: controlling supply as opposed to reducing demand

(4.1) The rise in cocaine consumption in Europe

The first anti-drug strategy that the EU adopted for the period 2000-04 was aimed mainly at achieving a ‘considerable reduction’ in consumption and availability of drugs in Europe.[48] This goal has not been met. Consumption of narcotics increased in almost every category of drugs, including cocaine.[49] It is estimated that 12 million Europeans have tried cocaine at least once in their life; in 2007 alone, an estimated 3.5 million adolescents and young adults used the drug.[50] Altogether, nearly 4.5 million Europeans sniff cocaine regularly. According to some estimates, 250 tonnes of cocaine are smuggled to Europe from South America each year. While cocaine consumption among US adults has dropped by 50% compared to 20 years ago, consumption in Europe has been on the rise since the mid-1990s.[51] Although the US remains the largest market for cocaine, with an annual import volume of around 450 tonnes, Europe is catching up quickly: whereas the amount of cocaine seized in the US has been on the decline since 1990, at the same time there has been a significant rise in seizures in Europe and West Africa. This is a clear indication of the growing volume of cocaine making its way into Europe. In the EU, cocaine-related crimes rose 62% between 2000 and 2005. Meanwhile, the increase in Europe is not distributed evenly among EU countries. In Spain, 16,799 cocaine-related crimes were recorded in 2000; but the number soared to 46,200 in 2006.[52] In Spain, Italy and France, cocaine consumption has trebled in recent years and in the UK it has quadrupled. Britain accounts for 26% of Europe’s cocaine consumers, followed by Spain with 24% and Italy with 22%. With 3% of the adult population consuming cocaine in 2008, Spain leads the countries of the EU. At the same time, consumption has grown significantly in Spain and Britain among adolescents: 6% of Spanish adolescents aged 15 and 16 have consumed cocaine at least once in their life.[53]

(4.2) Controlling supply: Management of prices

In the war on narcotics there are two fundamental strategies: (1) controlling the supply of drugs; (2) reducing demand. Tools for controlling supply can be applied in each phase of the production and commercial chain involving cocaine, from the growing of the raw material, coca leaves, to sale of the drug to the final consumer. These strategies include:

- Controlling chemical pre-cursors.

- Eradicating coca crops.

- Alternative development measures (AD).

- Enforcement measures along transit routes and at borders.

- Prosecution in producing, transit and consumer nations.

Elasticity of demand for narcotics. Tools for limiting supply seek to have an impact on prices as a lever for cutting consumption. The implementation of tools for controlling supply is based on the idea that prosecution of drug offenses, eradication of coca crops, seizure of chemical pre-cursors and cocaine or its base products(coca leaves, coca paste or cocaine base) make the drug harder to obtain and thus raise its price. At the same time, when the price rises, both at the wholesale and street-dealing level, demand for cocaine supposedly falls. In order for demand and consumption to be manipulated through price, consumers must react to price changes by adapting their consumption habits: reducing it when prices go up, and increasing it when they go down. In economics this mechanism is defined as elasticity of demand. It was once believed that narcotics, especially alkaloids, had very rigid elasticity that was close to zero. In other words, consumers would put up with price increases and pay any price to obtain drugs, because of high levels of addiction. But now most experts believe that drugs’ elasticity of demand is relatively high, and that consumption patterns do react to changes in price.[54] In the case of cocaine, the demand elasticity is said to be between -0.5 and -1. That means that if the price of the drug goes up 10%, demand will go down between 5% and 10%.[55] An alternative mechanism is cross elasticity of demand: a rise in the price of one drug causes more consumption of another drug as an alternative. But with drugs it is hard to ascertain the relationship between different kinds.[56] Because of simultaneous and frequent use of different drugs –a habit that is common among addicts– one does not know for sure if some drugs are substitutes or complements.[57] Given the uncertainty surrounding drug consumption, control measures should not be limited to one class of drug, but rather address all similar narcotics in order to avoid potential substitution mechanisms, ensuring that price levels remain comparably high.

On one hand, the high price of drugs reflects the risks taken by those participating in the drug trade, such as being prosecuted by law enforcement authorities or falling victim to the violence that is endemic in illegal markets. At the same time, drugs and their precursors that are lost in seizures and checkpoints keep prices high or even push them higher still, a phenomenon that can be seen of late in Mexico. Cocaine and heroine are products that come from the earth, with low production, growing and refining costs in countries with very low wages and abundant land for sowing crops. Under normal circumstances, the price of a dose of cocaine or heroin would have the same commercial value as a tablet of aspirin.[58] The risks stemming from the illegality of drugs and the costs that result from losses in frequent seizures are responsible for their high prices. In that sense, drugs are no different from other banned substances.[59] This is one of the main arguments of those who oppose legalisation, calls for which reappear with a certain regularity:[60] in fact, it is assumed that legalisation of drugs would trigger a fall in their commercial value, as prices would be freed from the risks and costs of illegality. If a drug is cheaper, consumption of it would go up quickly, assuming that drugs’ elasticity of demand is as acute as it is said to be.[61]

Drug consumption continues to be based on the logic of prices, and that is what supply-control mechanisms are based on. Intervention in the commercial chain of a drug is justified when it affects its final price. The real effect depends on the value that is added to the drug by the threat of criminal prosecution or seizures, which works as a royalty tax on illicit goods. The following calculation serves as an example of this logic.

How the price of cocaine is set. For the amount of coca leaves needed to produce a kilo of cocaine, an Andean grower receives about €250.[62] That kilo has a commercial value of nearly €1,200 for a middleman in the producer country. That same kilo, while in transit, has a wholesale price of between €12,000 and €15,000.[63] This kilo of relatively pure cocaine, later mixed with additives, sells on the streets of Madrid for €80,000, depending on the purity and the number of doses. Figure 3 illustrates the multiplication of value throughout the production chain. Rather conservative estimates are that fluctuations in the prices of coca leaves in producer countries would have no effect on the final price of the drug.

Figure 3. Multiplication of cocaine’s value in the commercial chain

The value of the raw material, that of the coca leaves, is too low and accounts for a tiny, almost invisible part of the wholesale price or the final price.[64] In the hypothetical case in which the price of the leaves needed to make a kilo of cocaine were to multiply by 10 and reach €2,500,[65] a gram of pure cocaine sold on the street would cost only €2.5 more. Keeping in mind that in Spain in 2006 cocaine had an average purity of 50%, multiplying the price of coca leaves by 10 would mean added cost for the final consumer of just over €1 per gram.[66] Considering that the average price in Spain is between €50-60 per gram, one euro more –the dealer probably would not even charge it – would have no influence on a person’s decision on whether to consume.

The risk of displacement. Efforts to control the supply of drugs always run the risk of being negated by the ‘balloon’ effect: when you squeeze a balloon hard, the air inside moves and bulges out somewhere else. The balloon metaphor is a vivid illustration of a problem that simply shifts somewhere else, rather than disappearing when it is resolved. In the war on drugs, we frequently observe displacement effects in the eradication of crops, alternative development programmes –illicit crops being replaced by others which are legal– and controls on transit routes. An increase in government surveillance of a region or a transit route, generally just over the short term, causes a drop in supply and raises prices, or leads to more additives in the final product. If there is a margin for finding alternatives, thanks to weak or limited governance structures, in a short span of time the aforementioned balloon effect occurs. This is true for growing and refining, as well as transport routes. If a product is illegal, then limited governance, especially in the realm of security, offers comparative advantages to its sellers.[67]

Many countries have the right weather and geographical conditions for growing coca leaves and opium. However, just four of them (Afghanistan, Bolivia, Colombia and Peru) account for 90% of all coca and opium crops.[68] There are also few countries that attract massive flows of drug trafficking. Therefore, it should be a central goal of international drug enforcement agencies to raise the costs of illegal activities in those countries.

4.3. Managing consumption directly: reducing demand

Drug-producing countries tend to stress that consuming nations are equally responsible in the international war on drug trafficking. ‘Without demand, there is no supply’ is their ceterum censeo in multilateral anti-drug forums. As opposed to controlling supply, the idea is that it is up to consuming nations to reduce demand as their share of the job in the battle against narcotics. Strategies for cutting demand do not address the price of illegal drugs, which is a tool for controlling supply, but rather go directly to managing consumption. These measures, which have proven to be successful in some countries of the EU, are based on prevention, therapy and harm-reduction. The goal is to warn potential consumers of the dangers of using drugs, treat addicts in a reactive fashion and reduce harm associated with drug addiction, such as being infected with AIDS and the worst kinds of hepatitis. These tools, long applied in Europe, include public awareness campaigns, arrangements for drug consumption under medical supervision, supplying addicts with clean syringes and a wide variety of therapeutic approaches. But they also feature penalisation of consumption and criminal prosecution for it, which, along with the social stigma associated with drug use, has a strong dissuasive and preventive effect. At the same time, the incarceration of consumers and small-time dealers, who are often drug addicts themselves, are ways to control demand. It is hard for addicts to consume drugs in jail. Statistically speaking, incarceration of drug consumers reduces demand for narcotics.[69]

As international anti-drug policy encompasses a wide range of foreign and domestic policy, many governments have a hard time establishing the right balance between controlling supply and reducing demand. Tools for controlling demand are intensely debated because they seek to administer consumption but not repress it. In almost all international conventions and statements on the world’s drug problems we find a balanced approach between policies to control supply and demand. That means producing and consuming countries should be obliged to work together to fight the problem. The European Council reconfirmed this concept of shared responsibility in its European Drug Strategy (2005-12) as a foundation of EU anti-drug policy.[70]

At the same time, producing and transit countries have been forced to acknowledge the need to adopt and implement policies for cutting demand, as they have been hit by growing levels of consumption. Some statistical analyses of the drug market in the US show that tools for controlling demand are more efficient than those aimed at controlling supply.[71] However, the anti-drug efforts of many governments concentrate on mechanisms for cutting supply. The CND, in a reflection of the position of many its member countries, considers supply-side tools to be fundamental in the international effort against drugs. They confirmed this in the political declaration and plan of action adopted at the 52nd session.[72] European states failed in their effort to seek a fundamental change in international anti-drug policy.[73] They did not manage to impose an approach more focused on public health, harm-reduction and controlling demand. The hoped-for change was not achieved despite strong international support for Europe’s positions, such as the manifest from the Commission on Drugs and Democracy, made up of the former Presidents of Brazil, Colombia and Mexico (Fernando Henrique Cardoso, César Gaviria and Ernesto Zedillo). It declared the war on drugs to be a failure, and called for a revision of policies based on repression and instead an approach based on public health.[74]

Political options I: controlling supply in drug-producing countries

How should one design an efficient international supply-control policy that would be a conceptually appropriate companion to domestic policies for reducing demand? What political options do the EU and its member states have for effectively controlling the supply of cocaine and its final price, and consumption within the EU? Here will analyse three supply-control tools for drug-producing countries, looking at their efficiency in relation to costs and how they function: (1) crop eradication; (2) alternative development; and (3) controlling chemical precursors.

5.1. Option I: crop eradication

Aerial fumigation and manual eradication in the Andean region. Over the past three decades, US governments have pursued coca crop eradication programmes as an adequate measure in the international battle against narcotics. The State Department says crops are the weakest link in the cocaine production chain because of their high visibility.[75] Since the 1980s, US governments have either supported eradication programmes in Latin America or carried them out themselves. Many times US representatives have called for cooperation from their European colleagues. European refusal to get directly involved in eradication efforts has irritated the US on more than one occasion.[76] The EU and its member states have an ambivalent position on eradication. The EU drug strategy does not rule out eradication altogether, and says it is important when associated with alternative development programmes. But the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), based in Lisbon, questions whether eradication is effective.[77]

How does eradication work? Under its Andean Counterdrug Initiative, the US State Department provides financing and technical support for supply-control programmes in seven Latin American countries. The basic pillar of the initiative is Plan Colombia, initially developed by President Andrés Pastrana in 1999. At first it proposed an overall approach addressing the war-torn country’s peace process and the drug problem. During the two presidential terms of George W. Bush, the US Government provided more than US$6 billion to the Colombian government under Plan Colombia. Recently, and unexpectedly, the Obama Administration confirmed the US commitment to the Plan Colombia and contributed nearly US$500 million from the budget for the new fiscal year.[78] Even though Plan Colombia was initially an all-encompassing initiative, most of the resources have gone to military purposes such as strengthening and training the Colombian army, buying new equipment and weaponry, and waging campaigns of mass eradication of coca crops. In Colombia, coca and opium poppy plants are either uprooted manually or fumigated from planes with the herbicide glyphosate. In the latter case, US contractors work with the Colombian national police. In 2007 alone, nearly 160,000 hectares were eradicated, according to the UN. According to the US Justice Department, 2007 was the sixth straight record year for eradication.[79]

Because of probable environmental damage from aerial fumigation and improved territorial control by Colombian security forces, manual eradication of coca crops is used more and more. In 2008, for the first time more crops were eradicated manually than from the air.[80] In the 1990s the US had financed manual eradication programmes in Bolivia and Perú.[81] The so-called Plan Dignidad, launched under the Presidency of Hugo Banzer in 1997 with US assistance, temporarily achieved a huge reduction in illegal crops in Chaparé, one of Bolivia’s main coca-growing regions. But the success was short-lived, and the coca-growing industry simply moved to other areas, mainly to Yungas.[82] In Bolivia, the coca-growers are very well organised and tend to put up fierce resistance to campaigns of forced eradication –which have been implemented even by President Evo Morales, who was a coca grower himself– to reduce crops used to make cocaine.

Precarious results. The growing amount of crops eradicated in Colombia only appears to be a success. Many of the effects of eradication can be neutralised with more efficient growing and refining methods, by replanting or by shifting crops to areas that are less accessible and visible. These evasive strategies are reflected at the price level: even though prices of coca leaves in the three producer countries are above the average seen in the 1990s, the commercial value of cocaine in Europe and the US has been falling since the 1980s. This casts serious doubts on the effects of eradication. If eradication campaigns helped limit the availability of cocaine for consumers, they would be seen in a different light. However, in illegal markets in Europe and the US cocaine has always been available to consumers.[83] The argument that each coca leaf harvest that is destroyed means less cocaine for consumers is simplistic and inaccurate: coca-growing and its refining into cocaine are governed by the laws of supply and demand. Their production is in determined by demand. A given amount of coca leaf or cocaine that is destroyed or seized is replaced, with no effect on the market. Major variations in the commercial value of coca leaves would not have a significant effect on the final price of cocaine or on the habits of consumers, as we showed earlier. From a commercial and price-level standpoint, eradication of crops does not achieve the desired result, so long as there is a margin for the balloon effect. As there are abundant areas in the Andes region with limited governance, neither the price nor consumption levels of cocaine are influenced by eradication programs, no matter how strict they are.

Aerial fumigation and displacement of crops has negative side effects. The potentially harmful effects of glyphosate on persons, flora and fauna have been the subject of intense debate.[84] The displacement of crops to increasingly far-flung and previously untouched regions is hurting sensitive ecosystems. Deforestation and the use of fertilisers and other chemicals destroy the tropical jungle and threaten biodiversity.[85]

In October 2008, the Government Accountability Office, the investigative branch of the US Congress, released an evaluation of Plan Colombiathat concluded that the eradication campaigns had had only modest results. The improvement in the security situation received a positive assessment, as did progress in reducing opium crops, although these are less visible than those of coca leaves. However, the report said the central goal of Plan Colombia –reducing the growing of coca leaves and production of cocaine by one-half between 2000 and 2006– had not been achieved. In fact, the GAO said that in 2006 the volume of coca grown surpassed that of 2000 by 15% and that cocaine production had risen 6% since the launch of Plan Colombia.[86] In the same period, cocaine trafficking to the US rose even though since 2000 and with help from the US more than 1 million hectares of illicit crops were eradicated.[87] The scarcity of cocaine in the US market between 2007 and 2009, the dramatic rise in the price of the drug and its lower grade of purity in the same stretch of time apparently stem from the situation in Mexico[88] and not from eradication drives in producer countries, as argued by government officials. This reading of the data is the most logical one, as cocaine production during this same period remained steady at nearly 1,000 tonnes a year. So the complications in the US market were the result of logistical and supply problems, not a drop in production. The GAO report shows that, as impressive as the numbers might be, the eradication programmes undertaken as part of Plan Colombia had no effect on production levels, final prices or consumption habits. The argument that were it not for the eradication the production of narcotics would have multiplied, cannot be verified because of theex post and hypothetical nature of that assertion. The commercial logic driving the drug trade casts doubt on the idea that cocaine production can soar regardless of what the level of demand is.

5.2. Option 2: alternative development

The paradigm of alternative development. The goal of alternative development programmes is to turn areas where illicit crops are grown into plantations for legitimate agricultural goods and to integrate them into the formal economy, allowing farmers to earn their livelihood legally. The EMCDDA says the EU and its member states are financing 37 alternative development projects in South America to the tune of more than €140 million.[89] At the same time, the EU supports producer countries in their efforts to market alternative crops through preferential trade agreements. The EU has also signed preferential treatment agreements with the Andean countries and those of Central America, which can export nearly 90% of their goods duty-free to the EU. For the EU and most of its member states, alternative development programmes are the central pillar of their international anti-drug policy. However, European governments are not the only ones that implement alternative development projects or programmes as a way to control drug supplies. Since the 1970s the US has supported many such programmes in Latin America. Between 2000 and 2005 alone, USAID administered US$1.6 billion in alternative development projects.[90] Just as the Colombian government is doing with its “Familia Guardabosques”[91] programme, which combines AD and crop eradication, the US government is using AD projects as an incentive for farmers to stop growing coca, opium poppies or marijuana.[92] Here, we see the main difference between these initiatives and European DA programmes, which do not have strings attached.

In the past a series of problems has arisen when alternative development projects are implemented.[93]

- Areas where illicit crops are grown are marginal and lack infrastructure, so it is hard for alternative crops to reach formal markets, both at the national and international levels.

- Crops are simply shifted to another area, rather than undergo substitution (this is the so-called balloon effect).

- Coordination is difficult between eradication of illicit crops and the availability of alternative development measures.

- Resistance from armed non-government groups and the precarious security situation in many areas where illicit crops are raised.

- A lack of legal security and clearly defined deeds to property, which makes long-term investment risky.

- The comparative disadvantages of alternative products compared to coca leaves and cocaine.[94]

In order to overcome or avoid these difficulties, these days aid agencies from the countries of the OECD offer all-encompassing alternative development programmes that go beyond simply replacing illicit crops.[95] In addition to this, measures are taken to improve infrastructure in crop-growing areas and open access to formal markets, support community development, institute training programmes for children and adults, establish legal security for peasants, encourage peaceful resolution of conflicts, etc. This broader focus seeks to overcome the problems inherent in alternative development programs and create a series of incentives that makes it more appealing and more secure over the long term for farmers to give up growing illegal crops. Other preventive measures aim to discourage migration to areas where such crops are raised. These measures attempt to encourage local development in regions where people might be tempted to move to areas where drug-destined crops are grown.[96]

The difficulty of defining goals. Alternative development projects tend to be assessed in terms of the results they achieve in replacing illegal crops with legal ones and whether this substitution is sustainable or not; for this reason, the evaluation does not centre on resolving the difficulties we discussed earlier. The fundamental question is not whether the day-to-day problems that might arise by implementing an alternative development project are resolved. Rather, it is whether alternative development tools are adequate for achieving the main goal of controlling the supply of drugs, their price and availability and, therefore, consumption of them. The question is not usually posed by donor governments nor the ones receiving aid, even though alternative development, at least among member states of the EU, is seen as the backbone of international anti-drug policy. Each measure for controlling supply should be analysed in terms of a drug’s price and availability for final consumers. It is noteworthy that this question is not debated in the corresponding alternative development forums. As we already stated, even major rises in the commercial value of coca leaves in producer countries will not have a visible effect on the final price of cocaine in the last link of its commercial chain.

This is true both for eradication and alternative development projects; in the end, both methods share the same logic. Therefore, the central goal of controlling international supplies of drugs –making them more expensive– cannot be achieved through alternative development projects. Even supposing that crops were effectively transformed, they would only be displaced, not replaced, beyond what happens at the local level. This is very similar to the consequences of massive eradication. For this reason, the GAO could not state that the more than US$500 million invested in alternative development projects as part of Plan Colombia since 2000 had had observable effects on crops. Rather, it is likely that crop displacement reduced the potential success of local DA projects to zero.[97] A true substitution of illicit crops beyond the local level could be attained if the alternative crops drew a price higher than that of coca, if there were sufficient infrastructure to market them and if farmers had more legal and financial security. However, the middlemen in the cocaine business –the ones who buy the raw material from the coca growers– can pay more, offsetting the possible commercial advantages of the alternative products. Taking into account the wide margins present in the cocaine trade, there will be no shortage of resources, and even less so because of the possibility of price rises being passed on to the next stages in the production and commercial chain.

From a political standpoint, alternative development projects are more attractive for Europe than crop eradication or other more repressive measures. They have a reputation as being more humane and socially-oriented, while crop eradication methods strip farmers of their livelihood and harm the environment, and perhaps even people. However, neither method has been shown to be an efficient tool in controlling drug supplies. Alternative development projects make sense when they break the feedback relationship between development and drug trafficking. They also make sense when they do away with war economies that fuel combatants in endemic internal conflicts in several producer countries.[98] In this way one can contribute in a sustainable way to solving structural problems, which in turn have made it easier for drug trafficking and related businesses to take root. Furthermore, one can consider the important contribution that alternative development makes to supporting the establishment of structures of good governance. This can be encouraged by an integrated approach, the one we described earlier, which over the long term could curb the displacement and extension of crops used to make drugs. Alternative development projects make no sense if the goal is to control the supply of drugs or intervene in the drug-consumption habits of people in Europe or the US.[99] So, alternative development should not be considered a pillar or stand-alone contribution to Europe’s international drug control efforts. Prolonging this belief would encourage false expectations, freeze resources that can be used more efficiently elsewhere and hinder a re-working of the approach. DA programmes can no longer be evaluated in terms of their performance in reducing crops used to make of illegal drugs, which is a goal which they cannot fulfil. What can be assessed is the extent to which DA tools alleviate the structural problems that contributed to the drug economy taking root in certain areas.

The alternative approach must go hand in hand with systematic control of the international transit system. Only by interrupting the commercial chain of cocaine or other drugs can one achieve a sustainable transformation of areas where illicit crops are grown into ones with legal alternatives. Farmers who grow coca leaves would stop growing them, or opium poppies, for the same reason that it is so difficult to grow alternative crops: without access to global markets, there is no way to sell them and thus no crops.

(5.3) Option 3: controlling chemical precursors

Chemical precursors are crucial for producing cocaine and many other narcotics. They are needed to convert organic material into a drug, refine it and purify it. Controlling trade in these substances is an important tool in controlling supply, as these precursors are a weak link in drug production. Controlling chemical precursors is not limited just to producing countries; it also seeks to restrict their availability, and for this reason there is debate over the usefulness of this as a tool in controlling supply in or near the producer countries. The United Nations Convention against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, of 1998 (also known as the Vienna Convention), regulates trade in precursors and it is implemented by the INCB. There are now 23 listed chemicals which can only be bought and sold in a restricted fashion. Most of these substances have more than one use and tend to be obtained through legal trade channels.

In its strictest dimension, the control of chemicals agents used to made cocaine is limited to potassium permanganate (KMnO4). It is key to making cocaine but also has a wide range of legal industrial uses. This chemical is the only cocaine precursor that is listed on schedule 1 of the annex to the Vienna Convention of 1998, which imposes stricter international rules on trade in this substance. To enhance the control process, the EU has signed special accords with all the Andean countries, except Venezuela, on trade in chemical precursors.[100] These agreements facilitate the certification of the end recipient in precursor export deal originating in Europe. However, the amount of KMnO4 required to refine and purify cocaine are relatively small compared to that of other chemical substances needed for this process, such as sulphuric acid, sodium carbonate and acetone. In 2007 and 2008, 26 countries reported legal exports of KMnO4, with volume totalling 2,400 tonnes.[101] Despite the EU’s strict regime of control and certification of end users, it cannot be ruled out that small amounts of precursors were diverted for illegal purposes. In 2006 the Colombian authorities alone seized nearly 100 tonnes of KMnO4 and destroyed 15 illegal laboratories used to produce it. This shows that no all precursors are of foreign origin.[102] It seems practically impossible to shut down all conduits through which this chemical reaches labs where cocaine is made. Imports of larger amounts of precursors for industrial purposes by some countries (Argentina, Brazil and Chile) that border on cocaine-producing nations are legitimate. But this sets up a mechanism for small amounts of multiple-use chemicals to be diverted. The strict control regime that exists within the EU has limited reach in producer countries and their neighbours. Although the control mechanisms need constant verification and updating to curb this illegal diversion, options for intensifying control on these chemicals seem to be fewer than with other tools.

Political options II: international control of supply in transit countries and areas

As we have shown earlier, as far as having an impact on the setting of the final price of cocaine, neither eradication campaigns nor alternative development projects are effective tools for controlling supply. The options for intensifying control of chemical precursors seem to have been exhausted. Since systematic control of supply in the Andean region began 30 years ago, volumes of coca crops and availability of cocaine for the world’s consumers have remained practically unchanged. Furthermore, the price of cocaine has fallen steadily, reaching very low levels. If one considers the rather modest results achieved so far by policies to control supply in producer countries, how effective has this control been in transit countries and areas? Depending on how close they are to producer and final-destination countries, we can distinguish several tools of control, which we will analyse here.

(6.1) Transit control near producer countries

Along with crop eradication, the governments of the producer countries and the US try to interfere with drug trafficking within the region and in nearby transit countries. One well-known example of these policies was the interdiction of air traffic in Peruvian territory near its north-eastern limits, a practice carried out by the Lima government in the 1980s and 90s in close collaboration with US forces. The interdiction regime was imposed to eliminate drug-related flights between the countries that grew coca leaves –then just Bolivia and Peru– and Colombia, the main cocaine-producing nation. Intense air traffic in light planes supplied Colombian laboratories with cocaine base from Bolivia and Peru. In the 1980s there was not yet much coca being grown in Colombia, but cocaine refining labs were concentrated there. The enforcement of interdiction –the idea was to intercept forcibly non-identified planes– reduced illegal traffic considerably along this route. But Colombian drug traffickers reacted by establishing alternative routes, for instance through Brazil, where the current regime of strict air traffic control did not yet exist. What is more, and this was even more serious, the Colombian cartels started to encourage coca-growing in their own country. While coca production in Bolivia and Peru declined because of the closure of the commercial chain and simultaneous eradication campaigns, it rose significantly in Colombia. The total surface area of illicit crops in the three countries remained virtually unchanged between 1992 and 2002. Within them, crops were just moved from one place to another.[103] Not just the US got involved in controlling regional transit, but also the EU, and some of its member states sought greater control over transit in the Caribbean. Between 1997 and 2001, the EU worked with the US and Canada under the Barbados Action Plan. Under this initiative, the small countries of the Caribbean and the secretariat of CARICOM received support and training to improve their systems for controlling their land and maritime borders and broaden cooperation by the security agencies.[104]

The control regime in Latin America has proven to be very efficient, as seen in the numbers: 56% of drug seizures around the world in 2006 took place in South and Central America. The Colombian authorities alone accounted for a quarter of the confiscations. More than half of the cocaine seized in 2006, almost 400 tonnes, was confiscated in an early phase of the commercial chain. First of all, in this early stage the commercial price of the drug is still very low. Secondly, early seizures can be replaced easily, given the proximity of places where coca is grown and refined. Thirdly, the loss of drugs that are seized cannot only be offset by cocaine that is in storage, but also with cocaine that is in transit: it is simply cut with higher percentages of additives in later phases. Therefore, control of transit in or near producer countries, as efficient as it may seem in light of the high numbers of seizures, has only a limited effect on the final price and availability of cocaine for consumers.[105]

(6.2) Transit control near the final consumer

The effectiveness of seizures near the consumer. However, seizures that take place late in the commercial chain, closer to the consumer than to the producer, have a higher probability of being effective and affecting the final price of the drug. Near urban markets in European countries or the US, the price of the drug is higher: 10 tonnes of cocaine seized in the port of Santa Marta, Colombia, have nearly the same commercial value of one ton that is seized the territorial waters of Ghana.[106] Border control agencies and monitoring of maritime routes are what make the price of illegal goods rise, such as drugs. Production and logistical costs account for only a tiny part of the final price. It is obvious that transit control measures only make sense if they are carried out near the final consumer; in the case of the EU, very close to the common external border.[107] Only there will an effect on price and possibly the availability of the drug be noticed. The impact on drug trafficking networks is greater when the drug is seized in the later phases of the commercial chain. In this case it is harder to replace confiscated drugs because the original source is so far away. Furthermore, there tend to be losses at earlier control points, as well. So the damage is greater for the traffickers, who will probably pass on the cost of these losses to the final consumer.

An empirical example of this logic was the doubling of the price of cocaine between January 2007 and September 2008 in the US and the temporary scarcity of cocaine in some major US cities, along with an increase in additives detected in regular checks of cocaine.[108] These developments coincided with the intense police and military campaign that the government of Mexican President Felipe Calderón had been waging against drug cartels since 2007, along with an escalation of the war between the cartels themselves.[109] The fight among and against the cartels interrupts the commercial chain most frequently close to US consumers. The Mérida Initiative (2008-10), with funding of US$1.4 billion to fight drug trafficking in Mexico and Central America,[110] is supposed to have a similar effect on cocaine availability and price in the US, Mexico and Central America. The Obama Administration’s strategy of boosting control of its southern border with a greater police and military presence, re-equipping Mexican security forces and controlling the flow of small arms to Mexico will enhance the effects of the Mexican Government’s drive against drug trafficking. It is likely that over the medium term the price of cocaine will remain high, as supplies are disrupted fairly often. But this will depend on the Mexican cartels’ ability to shift their activities to Central America, a trend that is already emerging and a source of great concern for the region’s small and vulnerable States.[111]

How Europe controls transit. The European Drugs Strategy(2005-12) and the second EU Drugs Action Plan (2009-12) highlight support for controlling supply in transit countries and near the EU’s common external border as tools for its anti-drug policy. The EU is also considering using funds from its Instrument for Stability, which are budgeted for the period 2009-11, in projects to fight against trafficking in cocaine and heroin.[112] It is a stated goal of the European Commission to interrupt, in concentric circles, the flow of drug trafficking toward Europe.[113] As a method for controlling supply, this strategy makes sense, and it will be effective if it is implemented in a systematic way. So long as there are territories for traffickers to evade control –often territories in countries with very fragile structures of governance– organised crime gangs can seek alternative routes and avoid seizures and criminal prosecution. From a European perspective, the rule that should govern transit control should be the following: the smaller the radius of the circle of enhanced monitoring, the easier it will be to control a maximum number of possible transit routes. Given the empirical fact that the price of drugs tends to rise gradually when they get closer to the external borders of Europe, it seems a good idea to establish a rather small control circle around the EU.

So far the most important operational measure within the EU has been the creation of the Maritime Analysis and Operation Centre-Narcotics, based in Lisbon. It features active participation from seven EU member states, including Spain.[114] EUROPOL, the European Commission and some member states have observer status in this organisation. The centre has an operational mandate, and coordinates tasks of monitoring and enforcing maritime areas and air space over European waters. This job of keeping watch over the Atlantic is made necessary by the rise in cocaine trafficking to Europe in recent years and the growing importance of West Africa as a staging ground for trafficking into Europe. In its first year of operations, this anti-drug agency coordinated the seizure of nearly 30 tonnes of cocaine. In September 2008, the French government focused on the Mediterranean by founding the Centre de Coordination pour la Lutte Anti-Drogue en Mediteranée, based in Toulon. EUROPOL’s COLA project coordinates the efforts of anti-drug agencies of member states and contributes to improving transit control along the EU’s external frontiers.[115]

Organised criminals’ ability to evade. Europe’s tools for controlling narcotics are adequate, but it is not clear that they are based on a consistent strategy to block drug trafficking to Europe in a systematic way. Seizures that are just occasional –as opposed to systematic– only contribute to causing drug lords to move their current trafficking routes, and not to cutting them off or decreasing their number over the mid- and long term. Drug trafficking rings learn quickly, and are flexible enough to adjust their strategies in response to those of government authorities. Traffickers’ most common way to rebuff increased government efforts is simply to move geographically.[116] They have sufficient resources, means and networks to shift to alternative routes, with different means of transport and new middlemen.[117] The rise in the commercial value of cocaine in the US, which is highly volatile and does not tend to last more than just a few months, shows the ability of drug rings to adapt to the temporary strategies of government authorities.[118]

With the fall off the Cali and Medellin cartels in Colombia in the 1990s, the hierarchical, pyramid-style structure in drug trafficking is now more the exception than the rule, although it seems this model has re-emerged in Mexico in a big way. The common structure in transatlantic drug trafficking is similar to horizontal networks, with smaller groups that interact autonomously and lack a vertical command structure. Each group tends to handle transactions in one or two of the links in the drug’s production and commercial chain.[119] It is believed that, at most, current drug lords run a coordinating body, as is thought to be the case with the Norte del Valle cartel in Colombia. These organisational structures are more like a holding company than the legendary figure of an all-powerful overseer. The advantage of this for organised criminals is that these decentralised structures cannot be wiped out with one definitive blow, as happened with Medellin cartel after the death of Pablo Escobar. The individual components of these organisations tend to interact without actually knowing their counterparts or possible bosses. The organisations can easily replace lower-level links, quickly filling holes left by arrests or violence waged by other groups.[120]

The constant interaction between law enforcement agencies and organised crime is similar to an arms race. The costs for both sides rise constantly, while neither can take advantage of their largest investments, which are swiftly neutralised. Unlike legal trade, trafficking in illicit goods does not tend to get more efficient over the long term. Rather, it becomes less economical and more costly.[121] Conventional means of transport must yield to more complex ones, and direct transport routes are replaced by more circuitous ones. Covering greater distances and crossing new borders raises costs for traffickers, but this is still cheaper than losing product and human resources. An arms race ends when the resources of one of the adversaries are depleted and it can no longer neutralise the enemy’s investments. This is not what is expected for the member states of the OECD, nor for drug trafficking networks, which tend to have abundant resources. However, many of the fragile states of West Africa which are affected by cocaine trafficking are very close to such a situation, if they have not already reached it.

The end of Europe’s passivity

For a long time, the EU and its member states have limited their activities in the effort to control the supply of drugs mainly to political dialogue and implementing alternative development programmes. Since the US cooperated with drug-producing and transit countries in Latin America, it was easy for Europe to let the Americans take the lead. As most cocaine-smuggling routes were the traditional ones –before the new African path to Europe was established– there were not many reasons either for the Europeans to react autonomously. These days, the African route, the growing consumption of cocaine in Europe and the amount of cocaine flooding the continent are forcing European countries to reconsider EU drug policy. Over the mid-term, the EU will have to make a greater effort of its own to control not just demand for but also the supply of cocaine. Countries such as Spain, the UK and Italy, which are suffering from a veritable epidemic of cocaine, will have to exert pressure within the EU for a repositioning of drug control policy. The US has done very little on drugs in West Africa. The resources that the US had budgeted for this area are insignificant compared with the money aimed at Latin America, is limited to just a few countries and tends to be linked to the fight against Islamic terrorism. But at the same time, in West Africa a safe haven has been set up for drug trafficking, relatively close to the European continent. How will the EU and its member states react effectively to this challenge?

7.1. Controlling transit in a strict sense