Only a quarter of foreigners from the most developed countries in the EU who live in Spain are pensioners. The rest belong to the active population, and their educational and occupational levels are higher than those of the Spanish population, and considerably higher than those of the rest of the immigrant population.[1]

Summary

Immigration to Spain from the most developed EU countries has trebled in the last 12 years, and, unlike previously, the vast majority of Britons, French, Germans and citizens of other rich EU countries living in Spain are now working immigrants, rather than ‘resident tourists’. As well as along the coast and on the islands, these EU foreigners now live and work in many other locations in Spain and constitute a population whose educational and occupational level is higher than that of the native population and distinctly higher than that of the rest of immigrants. Their number is unknown because many of them do not register either locally or with the Interior Ministry since, unlike immigrants from outside the EU or the most recent EU members (Rumanians and Bulgarians), they do not have enough incentives to do so. Their presence in Spain is highly positive, but it does force the education system to bolster English teaching so as to prevent their skills at certain professional levels from hampering Spaniards.

EU Immigration in Spain: Impossible to Know How Many

Studies on migration in the EU have traditionally differentiated between EU immigrants and non-EU immigrants and focused on the latter for economic, political and statistical reasons. EU immigrants enjoy more rights than their non-EU counterparts and, broadly speaking, are better qualified and occupy better jobs, while, with rare exceptions, they do not tend to pose problems when it comes to social integration. As for the statistical reasons, freedom of movement and place of residence and work within the EU for EU citizens means that they are not obliged in practice to register with the administration or apply for any kind of permit, which considerably reduces the number of statistical records in their connection.

In Spain, foreigners from EU countries are the oldest group of ‘immigrants’, already residing either permanently or for most of the year in Spain since the 1960sxties. At that time it was a population largely comprising Germans, Britons and French, and focused on the Mediterranean coastline and the islands; most were retired and attracted to Spain by the low property prices and cost of living here.[2] Along with this majority of pensioners, and as the tourist business boomed, European foreigners began to invest in the sector, opening, managing or working in restaurant and hotel businesses, mostly serving the foreign community. The concentration of this community in certain geographical areas and even in entire estates marketed in one particular country (and sometimes in one particular city or district), created a new job market linked to maintaining these homes and providing a range of personal services, and this market was filled mainly by foreigners from the same country. Aside from this immigration to coastal regions, at the end of the Spanish autarchy and with the advent of the first multinational firms in the 60s and 70s, a small number of highly-qualified professionals came to live mainly in Madrid and Barcelona.

Since then, the presence of citizens from the EU-15 has never stopped growing: in the last 10 years it has trebled, but this has gone largely unnoticed amid the much more notorious increase in the North African and Latin American immigrant population first, and that of Eastern Europe later. Accordingly, despite the steady increase, since 1996 immigration from EU-15 countries (in other words, prior to the 2004 enlargement to the east) has gone from accounting from almost half of the foreign population registered in Spain to less than one-fifth at present. By nationality, British citizens comprise the largest group (more than one-third of the total: 36%), followed at a distance by Germans, Portuguese and French. Overall, Britons, French and Germans account for two-thirds of all foreigners born in EU-14.

Table 1. Weighting of EU foreigners over total

| 1996 | 2000 | 2008 | |

| Total foreigners | 542,314 | 923,879 | 5,220,577 |

| Foreigners born in EU-14 (EU-15 less Spain) | 260,507 | 409,446 | 924,101 |

| EU-14 as a % of all foreigners | 48 | 44 | 18 |

| EU-14 growth (1996 = 100) | 100 | 157 | 355 |

Source: Spanish Statistics Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística – INE), Municipal Register and own research.

In fact, it is almost impossible to ascertain the exact number of EU foreigners residing in Spain. To start with, it is unclear what is meant by ‘reside’: most of those Britons, Germans, French and other foreigners spend some time in Spain while also maintaining their residence in their own countries, or travelling back and forth often now that flights are currently quite cheap. In the UK, for instance, it is cheaper to fly from London to Málaga than to travel by train or plane from London to Edinburgh. In legal terms, anyone spending more than three months in the country each year is considered to be a resident and, since 2007, ‘resident’ EU foreigners must register with the Foreigners Census as a prior step for inclusion in the Municipal Register, a requirement designed to improve knowledge of the number of Rumanian and Bulgarian immigrants, whose numbers have soared since their countries’ entry into the EU in January 2007. However, compliance with this regulation is overlooked by many local authorities and also many EU foreigners from countries in central and northern Europe do not register in either the Census or the Register, either because they do not know it is obligatory to do so or because they wish to continue to receive certain benefits in their country of origin which they would lose if they were found no longer to reside there, or for other reasons such as evading taxes, sidestepping the obligation to renew their driving licence every five years in the case of elderly persons or formally ‘importing’ the car they normally use and therefore paying tax on it. According to calculations by various embassies in Spain, more than half of their nationals who normally reside here have not registered with the local authority.

Accordingly, it is now very much more difficult to ascertain the precise number of EU foreigners residing in Spain than it is to pinpoint the number of non-EU foreigners in residence here. If we consider them to be ‘irregular’ residents if they are not registered, the percentage of irregularity is much higher among them than among non-EU foreigners. On 1 January 2008, 924,101 foreigners born in EU-14 countries were registered in Spain, while only 700,557 had residence permits, which implies a 24% irregularity, and this percentage would be much higher if we assume that most of them are not even registered. Among non-EU foreigners the percentage of irregularity was almost the same: 26% on the same date. However, among the group of foreigners born in EU-14 countries, the percentage of irregularity is extremely unequal: almost all Portuguese are registered,[3] whereas more than 40% of Germans and 39% of Britons registered with their local authorities have not registered with the Interior Ministry. In January 2008, there were 165,529 Germans registered with local authorities and just 95,415 had residence permits. A total of 206,000 Britons held residence permits, while 334,000 were registered, meaning that 39% were in an ‘irregular’ situation. And if we compare this figure with the 1 million Britons who the Foreign Office calculates own a home in Spain and spend time here each year, or the 17 million who visit Spain annually, we will conclude that it is impossible, based on current sources, to accurately ascertain the number of residents. The same is true of Germans: while 165,000 are registered with local authorities in Spain, German sources estimate that there are in fact between 500,000 and 800,000 in the country.

The Active Population Survey (Encuesta de Población Activa – EPA) for the final quarter of 2007, however, detected a total of just 562,000 foreigners born in EU-14 countries, although the selection of the survey universe might explain the discrepancy with the Municipal Register, since the EPA interviewed only those who state that they had been residing in Spain for at least one year. It is natural to assume that foreigners who have decided not to register either with the local authority or the Interior Ministry might answer no to the first few filter questions of the EPA survey and therefore be excluded from the sample. Furthermore, it is more difficult for the EPA to obtain responses from the most highly educated groups and those in the highest occupational levels –who are less willing to spend their time answering surveys– and this is precisely a distinguishing characteristic of EU foreigners, which might also explain their lower presence in the EPA.

Statistical sources enable us to differentiate between ‘foreigners’ and ‘those born abroad’ and the findings are very different in each case, since many of those born abroad but living in Spain have already obtained Spanish nationality, whereas, to make matters even more confusing, a percentage of those born abroad and now living in Spain are the children of Spanish emigrants of the 60s and 70s who have returned here. This is why this analysis shows only those born abroad, in any EU-15 country except Spain, who do not hold Spanish nationality, since, based on the data compiled by the Immigration Observatory (Observatorio Permanente de la Inmigración – OPI), very few EU foreigners have acquired Spanish nationality. This is because they already enjoy considerable rights and therefore rarely need to.

The variety of sources is such that this work will not attempt to estimate the total number of EU-14 foreigners normally residing in Spain, and it is restricted to analysing the characteristics of those included in statistical sources.

The study is based mainly on the use of the micro-data from the EPA survey of the last quarter of 2007, and, secondly, on the preliminary data from the 2008 Municipal Register, although other statistical sources are used, and are indicated where applicable.

An Active Population

EU foreigners have traditionally been depicted as pensioners in search of the sun living on the islands and mainland coasts, an image which painted a true picture of the reality during the 1970s, 80s and early 90s, but which must now be fine-tuned. At present, although most of them do still live in the traditional areas (South-East and Murcia, Balearics, Canaries and Andalusia), 42% now reside elsewhere in Spain, most notably in Madrid and Barcelona.

Table 2. Breakdown by area of residence

| Autonomous Region | % |

| Andalusia | 14 |

| Balearics | 7 |

| Canaries | 11 |

| South-East (Valencia + Murcia) | 26 |

| Catalonia | 14 |

| Madrid | 11 |

| Rest | 17 |

| Total | 100 |

Source: National Statistics Institute, 2007 Municipal Register.

There is some geographical specialisation by origin. The Germans are concentrated in the Canaries, Balearics and Valencia, whereas the British are easily the most numerous group in the South-East as a whole (46% of all EU-14 foreigners) and Andalusia (42%) and they are almost as numerous as the Germans in the Canary Islands. The French are only the most numerous group in Catalonia, but with a much lower percentage (15%). The greatest specialisation is in Galicia, where the Portuguese account for two-thirds (66%) of all EU-14 foreigners (2007 Municipal Register).

As for age groups, the population of EU-14 foreigners is still older than the native population, and much older than the rest of immigrant populations, who in turn are younger than Spaniards; however, the majority of all of them are in active population age groups. As for the breakdown by gender, overall there are more men than women (53%), especially among immigrants from Portugal and Italy, another sign that they are labour immigrants (see Appendix).

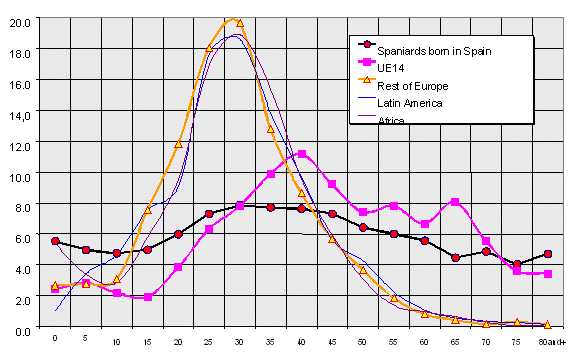

Chart I. Population by origin

This breakdown by age shows that they are no longer ‘coming here to rest’ as the author titled an article in 1995 in reference to EU immigrants,[4] but that, like the rest of immigrants, increasing numbers of Britons, French, Italians, Germans and so on are coming to Spain to work. Pensioners (over 65 years old) are now a minority, accounting for one-fifth of all foreigners from the EU-14 resident in Spain, and the rate of activity among the population in working-age groups (from 16 to 64) is basically similar to that of the Spanish population: 57% of EU-14 foreigners are economically active, versus 59% of the native Spanish population. Among EU foreigners eligible for early retirement, aged between 50 and 65, half of them are active (mainly men), a slightly lower percentage than among native Spaniards in that age group (59%). The inactive population aged between 16 and 64 are mostly ‘housewives’ (64%), students (6%) or early retirees (26%).

Table 3. Ages and ratio of activity among EU-14 foreigners

| Total (%) | |

| 0 to 15 years | 5 |

| 16 to 64 years | 74 |

| Active (16-64) | 57 |

| Inactive (16-64) | 43 |

| 50 to 64 years | 22 |

| Active (50-64) | 50 |

| Inactive (50-64) | 50 |

| 65 or older | 21 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

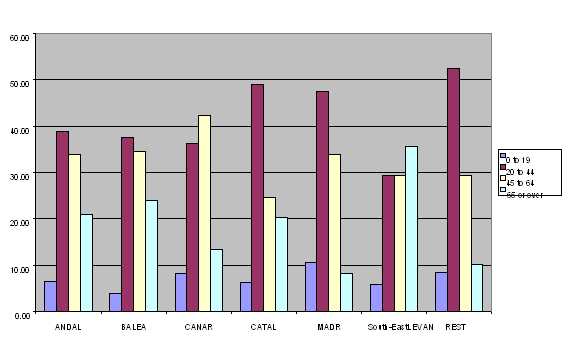

By region, only in the South-East does the percentage of inactive EU immigrants (64%) exceed that of active EU immigrants, while Madrid, because of the concentration there of multinational companies, holds the record of activity among EU immigrants. In short, only in the South-East does the profile of retiree or early retiree hold true as the majority, and in all other regions, most notably in Madrid, Catalonia and ‘the rest’, those working outnumber those who do not work.

Chart 2. Age groups by region

Table 4. Ratio of activity by region (population aged between 16 and 64)

| (%) | Andalusia | Balearics | Canaries | Catalonia | Madrid | South-East | Rest | Total |

| Working | 45 | 52 | 54 | 61 | 70 | 28 | 60 | 50 |

| Unemployed | 10 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 5 | 6 |

| Inactive | 45 | 44 | 44 | 34 | 27 | 64 | 35 | 45 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

As befitting their ages, EU-14 immigrants are a less active population than those from outside the EU or those from Eastern Europe –mainly from Rumania–. The difference is in line with that existing between the native population (Spaniards born in Spain) and non-EU or Eastern European immigrants.

Table 5. Ratio of activity by origin: Population in active age group

| (%) | EU-14 | Natives | Rest of Europe | Africa | Latin America |

| Working | 50 | 52 | 68 | 56 | 73 |

| Unemployed | 7 | 6 | 13 | 15 | 11 |

| Inactive | 43 | 42 | 19 | 29 | 16 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

A Population with a High Level of Education and Wide Range of Occupations

EU immigrants have a higher average level of education that the Spanish population and much higher than the rest of immigrants, which enables them to access higher-level jobs. Among EU-14 immigrants, the EPA’s findings reveal that just under one-third of them (31%) have university qualifications, versus one-fifth (22%) of the overall Spanish population (INE, Indicadores Sociales). The education level of EU immigrants is especially high in Madrid, where university graduates account for 53% of the total, followed by Catalonia, where the percentage is 40%, and it is unusually low in Galicia, where EU immigrants with only primary standard education are the majority, probably because of the greater presence there of low-skilled Portuguese immigrants.

This difference in education levels is much greater if we restrict the analysis to the central age group of the active population, from 20 to 44. Here there is a huge difference in education levels between immigrants from the EU-14 and those from the rest of the world: the former more than double the percentage of graduates from elsewhere in Europe and Latin America and outnumber the proportion of African graduates almost eight-fold.

Table 6. Educational level by origin: persons aged 20 to 44

| (%) | Natives | EU-14 | Rest of Europe | Latin America | Africa |

| Primary or less | 10.8 | 11.9 | 13.1 | 19.4 | 53.9 |

| Initial secondary | 28.6 | 16.0 | 14.1 | 19.4 | 16.7 |

| Professional secondary | 34.8 | 32.8 | 55.5 | 46.2 | 24.0 |

| University | 25.8 | 39.3 | 17.3 | 15.0 | 5.4 |

Source: EPA, media 2007; research by Luis Garrido.

At present, a number of European directives regulate recognition in other EU countries of regulated professional qualifications, some of which are ‘harmonised’ (medicine and architecture), which implies that qualifications obtained in a member state are automatically recognised in any other. But Spain has not yet transposed the latest directive (2005/36EC) and faces continuous complaints from the European Court for the obstacles which professional collegiate bodies from certain spheres place on the activity of professionals from other EU countries. There is a contradiction between the Spanish rules which oblige the members of certain professions to join collegiate bodies and the ‘free provision of services’ hailed under European rules. In the case of ‘unregulated’ professions, like IT specialists, it is not necessary to have obtained recognition and foreigners have no difficulties of this kind. However, it is quite a different story when it comes to equating academic qualifications from any other member state, a requirement which anyone wishing to teach or research in the Spanish public sector must meet. In that case, the process for certification of the qualification in accordance with its specific category (‘homologación a título concreto de catálogo)’ is slow, takes at least six months and in many cases requires people to sit examinations, which obviously makes European researchers more reluctant to move to Spain. Apparently, the so-called ‘Bologna Process’ should serve to standardise European university studies and make it easier for professionals to switch countries, but in fact, ever since Spain refused to make a catalogue of higher qualifications (previously known as licenciaturas or degrees) and allowed each university to design its own qualifications framework with no obligation to bring them into line with the rest of Spanish universities, not only has the process of equating qualifications not made any headway, but it has actually been severely impaired. At all events, the Science and Innovation Ministry (which now controls universities) has yet to clarify how the implementation of the new qualifications framework will affect the process of professional recognition and academic certification for graduates from other EU countries.

The increased number of economically-active EU immigrants has brought with it a broadening of their field of activity, which is no longer limited to the hotel and restaurant industry –although this is still the prevailing sector, alongside commerce–, accounting for 26% of those occupied, and followed by various administrative activities (18%, including real estate activities), construction (13%) and health and education (13%). Overall, the various industrial activities (except construction) account for 13%, services 71% and just 3% work in agriculture.

Compared to natives, EU-14 immigrants work less in agriculture and industry and more in construction, commerce and hotels and catering, as well as in financial, real estate and general administrative positions. The prevalence of commerce and hotels and catering is widespread in all regions, except Galicia, but it is especially marked in the Balearics and Canaries, where these two activities account for more than 40% of those occupied (43% and 42%, respectively), in other words, well above the 26% average and in line with the economic specialization on the islands. In Galicia, the breakdown of activities among EU immigrants is distinctly different from that of other regions and almost inverted. There, EU immigrants, who are mainly Portuguese (66%, according to the 2007 Municipal Register), have a similar profile to non-EU immigrants, and their presence is evenly distributed among the various industrial and services segments.

Table 7. Activity by origin

| (%) | EU-14 | Natives |

| Agriculture and fishing | 3 | 4 |

| Mining, food and textile | 4 | 6 |

| Other industries | 4 | 6 |

| Machinery manufacture | 5 | 5 |

| Construction, water, gas and electricity | 13 | 12 |

| Commerce and hotels and catering | 26 | 22 |

| Transport and finance | 6 | 6 |

| Real estate, IT, research, public administration | 18 | 13 |

| Education and health | 13 | 20 |

| Other | 8 | 6 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

Among these activities, their occupational position is notably higher than the average among natives: they double the percentage of natives among management personnel and exceed it among technical experts and senior and mid-level professionals, as befits their higher level of education and, often, their deployment in Spain as senior employees of multinationals. At the other end of the spectrum, there are fewer engaged in unskilled work, and this difference is much bigger when compared with non-EU immigrants.

Table 8. Occupation by origin

| (%) | EU-14 | Natives |

| Armed Forces | 0 | 0.5 |

| Management of companies and public administrations | 16.5 | 8.2 |

| Scientific experts and professionals and intellectuals | 17.8 | 13.9 |

| Supporting technical experts and professionals | 15.9 | 13.2 |

| Administrative employees | 6.6 | 10.2 |

| Restaurant, personal and protection services personnel, and sales personnel | 12.4 | 14.6 |

| Skilled workers in agriculture and fishing | 1.3 | 2.7 |

| Craftsmen and skilled personnel in manufacturing industries, construction and mining | 14.3 | 15.5 |

| Operators of installations and machinery, and assembly workers | 6.2 | 9.9 |

| Unskilled workers | 8.8 | 11.4 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

If we take as detailed as possible a look at the EPA data, we will obtain a more accurate view of how the occupation of EU-14 immigrants differs from the rest, both from natives (Spaniards born in Spain) and from other immigrants. This comparison clearly shows that EU labour immigration is different from all others, including that of the rest of Europe, which currently mainly comprises Eastern European countries. The clearest differences appear in the sectors that have typically acted as the entrance platform for illegal immigration in Spain: construction, household help and agriculture. Due to both their higher skill level and their entitlement to work and residence permits, EU-14 immigrants are underrepresented in these occupations (19%) which nevertheless account for 54% of immigrants from the rest of Europe and 44% of those from the rest of the world. In contrast, EU-14 immigrants double the number of natives working in education (many of them are probably language teachers) and also exceed their number in IT activities, both of which are fields in which immigrants from the rest of Europe and the world tend not to enter.

Table 9. Main activities by origin

| (%) | Natives | EU-14 | Rest of Europe | Non-European |

| Construction | 12.0 | 14.6 | 29.4 | 23.9 |

| Hotels and catering | 5.8 | 14.3 | 13.4 | 15.5 |

| Household help | 1.7 | 1.7 | 16.4 | 14.6 |

| Retail trade and repairs | 10.2 | 8.1 | 3.2 | 8.6 |

| Other services to businesses | 8.2 | 8.3 | 4.2 | 6.5 |

| Agriculture and stockbreeding | 3.2 | 1.6 | 8.0 | 5.5 |

| Public administration | 6.7 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Education | 5.8 | 10.1 | 0.2 | 0.6 |

| Health | 6.6 | 3.2 | 0.9 | 2.1 |

| Transport and telecommunications | 3.1 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 1.3 |

| Financial services | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| IT | 1.5 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 0.2 |

| Vehicle sales and repairs | 2.2 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 1.1 |

| Wholesale trade | 4.0 | 2.3 | 3.4 | 2.9 |

Source: EPA, media 2007; research by Luis Garrido.

As for their contractual relationship, EU immigrants outnumber Spaniards among the self-employed (both liberal professionals and technical services personnel) and entrepreneurs, and there are fewer in the public sector, while most, like Spaniards, are private sector salary-earners.

Table 10. Employment situation by origin

| (%) | EU-14 | Natives |

| Entrepreneur with employees | 8 | 6 |

| Self-employed | 24 | 11 |

| Public sector salary-earner | 3 | 16 |

| Private sector salary-earner | 64 | 65 |

| Other | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 100 | 100 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

By area, there is a clear difference between, on the one hand, the South-East coast and the islands, where entrepreneurs and self-employed account for a large percentage of those occupied (more than 40% in the Canaries and Balearics) and the rest, where salary-earners dominate. As regards contract type, EU-14 immigrants enjoy somewhat less employment stability than Spaniards (due mainly to their scant representation in the civil service), but much more than the rest of immigrants. 68% have indefinite contracts, versus 73% of natives, 42% of other Europeans (basically Rumanian), 43% of Africans and 50% of Latin Americans. This higher level of stability can be explained, as well as by their higher level of preparation, by the fact that EU-14 immigrants tend to have lived longer in Spain than other immigrants. 53% have been in Spain for more than eight years and 70% for more than six years.

Very few EU-14 immigrants were collecting unemployment benefit: 2% in the moment to which refers the source (4th quarter of 2007), a slightly smaller percentage than natives (3%), which in turn was exceeded only by the percentage among African immigrants (4%). The percentage of active population looking for work was 14% among EU-14 immigrants, somewhat higher than among natives (12%), but considerably lower than among Africans (22%), Eastern Europeans (19%) and Latin Americans (19%), further evidencing their higher occupational success rate.

Integrated Immigration?

Most elderly Britons and Germans, either pensioners or early-retirees, live in housing developments that have become ‘ethnic enclaves’. When these developments were promoted they were marketed almost solely in the UK or Germany and they attracted thousands of ‘residential tourists’ who chose to buy a home here, move here for all or most of the year and live off their pension which some years ago was more than enough to live comfortably in Spain. Services were established in these developments, like bars, restaurants, shops and small clinics, and gardeners, plumbers and electricians, generally fellow Germans or Britons, thereby found a way to live and work in Spain. The result is that ‘ghettos’ formed where immigrants or ‘residential tourists’ were able to reproduce their original lifestyle under the sun with no need to learn Spanish or any other of Spain’s official languages.[5]

The problems of this model have emerged as this population aged enough to require government help. Spanish economic growth in the last 20 years has translated into an increase in prices, and pensions which were sufficient in the 1980s are no longer enough to make ends meet in Spain. In the case of Britons, this is compounded by sterling’s recent decline against the euro. Furthermore, many elderly people, particularly elderly women, encounter serious problems of loneliness: they have no family in Spain and after many years living here they have lost contact with their families and friends in their country of origin, where, for the most part, they no longer have a home, since they sold up to settle in Spain. In a society such as Spain, where care for the elderly falls mainly to their families, they have no help and when they need to go to the doctor they find they cannot speak the language. The widow’s pension which, for example in the case of Germans, is 60% of a retirement pension, is often too small and many widows are experiencing relative poverty. If they were living in Germany they would receive up to €2,000 to finance a home, but living in Spain the maximum amount they may receive from the German state is €600. Accordingly, this aging population is asking the German state for more help, most notably the construction in Spain of subsidised homes for the elderly.

Municipal governments in coastal and island areas are increasingly aware of these issues, which affect many of their residents, and they are implementing initiatives to make life easier for the elderly and thus prevent them from leaving and also to prevent the publicity given to their plight in their countries of origin from discouraging others from coming. Within the typically tight limits of municipal purses, local governments (at least some of them) are developing programmes, for example, to increase mobility among the elderly by providing free public transport or funding translators at doctors’ surgeries.

The ‘enclave’ model as a way of life for wealthy-country EU immigrants residing in Spain has already been exceeded in number by the new immigration consisting of young individuals who come to work in a more appealing environment, and especially a sunnier one, than their own countries can offer them. As we have indicated, although many of them have found work or set up businesses in these enclaves, many others live and work in a Spanish environment and in inland areas. In the last few years there has been a major change in the way Spanish culture is seen in France, Germany and the UK, to name but three of the main sources of immigrants: in France Spanish has overtaken German as the second foreign language (obviously after English) and in the UK Spanish is now the first foreign language. Living in Spain is now attractive not just because of the sun, but also because of the food, the sociability, the schedule, and, as one British source consulted said, the less ‘strict’ rules and even the ‘lower levels of immigration’! These economically active immigrants are interested in learning the language and they encourage their children to learn it, they tend to marry Spaniards (although their exogamy is impossible to compare with that of other foreigners based on the currently available data)[6] and, overall, they are completely integrated in Spanish society.

A significant indicator of social integration is political involvement which, in this case, yields poor results. EU foreigners are entitled to actively and passively participate in the municipal elections of any member country in which they reside, since the European Parliament approved Directive 94/80, one of whose purposes was to help build a shared collective identity among all Europeans. In Spain, the Directive was transposed late, in 1997, and EU residents were first able to exercise their right to vote and stand for office in municipal elections in 1999, on two conditions, as well as the minimum age limit: they had to be registered with their local authority and they had to have a residence permit or have requested one. These requirements exclude the significant percentage of ‘irregular’ EU immigrants. Furthermore, unlike Spaniards, EU foreigners had to previously state their intention to vote, which only 21% of those registered did. In the 2003 municipal elections, those already registered did not have to repeat the process, but the total percentage registered scarcely varied nevertheless. As Mónica Méndez points out,[7] in coastal municipalities with large concentrations of EU foreign population, more of them registered (36%), but this is still a small percentage compared with the electoral turnout among Spaniards (64%). Although there are signs that this turnout may have increased, judging by various newspaper reports on the role of foreigners in the municipal elections of 2007, the data compiled by the Interior Ministry are not yet available for consultation.

Low electoral turnout among EU immigrants can be explained by several factors, some linked to the inability to speak the language among ‘resident tourists’ and the ensuing lack of cultural integration. Even when they do speak the language, if the local political parties do not explicitly target them, foreigners are not likely to identify with any of the options and they, therefore, tend to abstain. Furthermore, the requirement of prior registration to vote is a discriminatory measure which pushes down voter turnout. At all events, the local newspaper reports in 2007 appear to suggest that there has been an increase in political interest among foreigners in municipalities with a large presence of foreigners entitled to vote and the incorporation of foreign candidates, which has in turn boosted the number of local councillors from EU countries.

The fact that EU immigrants have normally abstained in municipal elections, as well as for cultural reasons, also has to do with the absence of major local conflicts which affect their daily lives. In this connection, there have been two substantial changes which have led to an increase in political participation in coastal areas: application of the Coastal Development Act (Ley de Costas) and approval of the Planning Act of Valencia (Ley Urbanística de la Comunidad Valenciana). The Coastal Development Act dates back to 1988 but its effective enactment was driven trough parliament in the last session and the result is that some 200,000 homes built within 100 metres of the seashore along the entire Spanish coast have been declared illegal. Of these homes, according to figures calculated by the association of people affected by the law (Plataforma Nacional de Afectados por la Ley de Costas), some 15% (around 30,000) belong to foreigners, mainly Germans and Britons, and the law states that all of these homes have become ‘public property’ subject to a 30-year concession to their current owners, which may be extended for another 30 years. In other words, the owners of these homes, some of whom are still paying for them, have suddenly found that they are no longer legally homeowners although they are allowed to continue using them, except in some rare cases where, for landscape- or environment-related reasons, the building is actually torn down, and compensation paid to the owners. Most of these homes were built legally when the mandatory distance from the sea shore was 20 metres, and not 100 metres as it is now, and if they were built after 1988, developers often secured a municipal licence from local authorities despite the planned buildings being inside the restricted perimeter. Application of this law is no doubt necessary to prevent ongoing destruction of Spain’s coastal landscape, but among its side effects is the negative impact on the capital of homeowners, most of whom bought their properties in good faith and had no knowledge that the Law made their buildings illegal.

Both the application of this already old Coastal Development Act and the more recent Planning Act for Valencia (2004, amended in 2006), which has been the target of hundreds of complaints and protests to the European Commission and Parliament,[8] have triggered unheard-of political involvement among EU foreigners in Spanish coastal areas: the formation of associations such as the very active Abusos Urbanísticos No (‘No to Planning Abuse’), protests at their respective embassies, interventions at European level and even the formation of local political parties, like Ciudadanos Europeos (in Mojácar, Almería). This has all likely had a positive impact on the political integration of EU immigrants who have been obliged to familiarise themselves with the ins and outs of the Spanish political, legal and administrative systems, although, as we have mentioned, we do not yet know the global effects of this on the turnout at the last municipal elections.

Furthermore, the crises triggered by the Coastal Development Act and the Valencia Planning Act sullied Spain’s idyllic image in the UK and Germany, and the situation has been further compounded in the last year by the property market crisis and its negative effects either on the prospects of homes appreciating in value or directly on the decline in value of those most recently purchased. In particular, the UK media published a great number of negative articles about house purchases on the Spanish coast and the failure of the sunny dream.

Conclusions

Although it has gone unnoticed in comparison with the rapid rise in non-EU and Eastern European immigration in the last few years, EU immigration from the most developed countries in the EU has almost quadrupled since 1996. Unlike previous decades, at present most immigrants from countries which already belonged to the EU prior to its eastward enlargement in 2004 came to Spain to work rather than spend their retirement enjoying the weather and low prices. They are still broadly older than the Spanish population, but most are still in active ages, with just one-fifth older than 65, and their occupation rate is similar to that of the natives. Geographically, they are dispersed throughout the entire country, although many of them are still concentrated in the mainland Mediterranean coastal areas and the Canary and Balearic Islands, where the existence of large communities of Britons and Germans has created a specific job market for their fellow citizens. With the well-known exception of the Portuguese, these are immigrants of high educational standards, higher than that of the natives, which enables them to access more highly qualified jobs and a greater degree of employment stability. These differences are obviously much greater when this immigration is compared not with native Spaniards but with the rest of immigrants arriving in Spain.

Intra-European employment migration (EU-14) towards Spain comes from countries which, again with the exception of Portugal, which has been in an economic recession so far this decade, post lower or similar unemployment rates to those of Spain and have standards of living and State welfare services on average superior to those in Spain. In this case, therefore, push factors appear to count for little, and what we see are pull factors which are not included in the scope of standard analyses of the causes of immigration: Germans, French, Britons and Dutch who come to live and work in Spain do so in search of better quality of life, a concept in which climate plays an important but not exclusive role.[9] They evidence the diversification of migratory movements throughout the world, which are no longer only from developing to developed countries, nor from north to south, but increasingly move between developed countries, and indeed between southern countries and developing countries in Africa, Latin America and Asia. This north-south intra-European immigration, against the flow of past decades, is the result of more equality between standards of living in the north and south EU, enabling extra-economic factors (weather, culture, sociability, family ties and language) to take on more central roles. Furthermore, this internal labour mobility within the EU has had a beneficial effect on the construction of a common European identity which shores up the EU’s political project.

From Spain’s perspective, the fact that ‘quality of life’ is an appealing factor is certainly an advantage when it comes to securing the arrival of skilled immigration which helps Spain to the detriment of its European partners. The role of foreign researchers, for example, is increasingly significant in universities and research centres in Spain, as evidenced by their websites, which implies a substantial contribution to boosting productivity in the Spanish economy. And this will be even more noticeable if the plans announced by the new Science and Innovation Ministry to attract foreign researchers succeed. In this connection, EU immigration from the more developed countries has the opposite effect to immigration from elsewhere in the world, whose lower-than-the-Spanish-average skill levels (comparing the same age groups) and whose occupation in the most labour-intensive sectors, has produced a statistical downturn in Spanish productivity. Furthermore, the increasing arrival of EU graduates to the Spanish labour market must necessarily have an impact on our education system, in particular language teaching:[10] in an information economy and society that is increasingly globalised, British, German, Dutch, Swedish and other graduates have a considerable advantage over Spaniards because of their knowledge of English, which today is a basic selection criterion in many industries, from hotels and catering to research centres. If Spaniards’ knowledge of English does not improve substantially, the competition by these highly skilled immigrants from other EU countries may pose a serious threat to many.

In view of these characteristics of European migration, it seems vital to improve the basic instruments for administrative registration so as to accurately ascertain the number of EU immigrants in Spain. The description of the characteristics of this population presented here is deduced from the findings of the Active Population Survey (Encuesta de Población Activa – EPA) and 2007 Municipal Register (Padrón Municipal), but these sources do not tell us exactly how many EU immigrants reside in Spain. We cannot even make an estimate, because of the considerable diversity of data from statistical sources and, above all, because, as qualified experts have repeatedly reported, this population is underrepresented in the Municipal Register. We can be reasonably sure that the EPA figure (562,000 people) is the minimum, but the real figure is likely to be much higher, perhaps double.

The current lack of knowledge in this connection, which derives from the inaccuracies of the population registers, has several significant negative effects, including its impact on the veracity of the Government Accounts, used to make a number of key decisions. For example, we cannot calculate the per capita income of a region or the productivity of the country as a whole without knowing the real size of the population. This first effect nationwide is important but vague. The second effect is specific and affects local and regional governments which are obliged to provide services to populations whose exact size they do not know. In smaller municipalities, this obstacle is easy to overcome, but this is not true in larger towns which are underfinanced because of the decision by many foreigners not to register. In the case of the autonomous regions, the lack of data brings problems in planning resources, in particular health resources, and difficulties in showing the Spanish central government and the EU governments of origin which part of the health budget corresponds to them. Health expenditure has become one of the main items of public spending in Mediterranean areas in which tourism and immigration of ‘resident tourists’ concentrate (especially in Valencia) and the mechanisms which should allow autonomous regional governments to recover these expenses are simply not working. For all these reasons, it is worth making a concerted effort to coordinate between central information compilation bodies (most notably the Statistics Institute – Instituto Nacional de Estadística) and local administrations to encourage this unknown number of immigrants to register.

Furthermore, the conclusions of this study point to the need to devote more attention to labour immigration from wealthy EU countries, which is now somewhat sidelined from the research in view of the increasing growth of immigration from Eastern Europe or the rest of the world.

Carmen González Enríquez

Director of the International Migrations Programme and Senior Analyst for Demography, Population and International Migrations, Elcano Royal Institute

Appendix

Table 1. Foreigners from EU-14 residing in Spain by country of birth, January 2008

| Total | Men | Women | |

| UK | 334,318 | 170,136 | 164,182 |

| Germany | 165,529 | 83,250 | 82,279 |

| Portugal | 113,093 | 72,590 | 40,503 |

| France | 94,063 | 47,507 | 46,556 |

| Italy | 76,088 | 48,063 | 28,025 |

| Netherlands | 42,583 | 22,378 | 20,205 |

| Belgium | 31,312 | 16,071 | 15,241 |

| Sweden | 18,624 | 8,502 | 10,122 |

| Ireland | 14,085 | 7,418 | 6,667 |

| Denmark | 11,090 | 5,683 | 5,407 |

| Austria | 5,407 | 4,175 | 4,270 |

| Greece | 3,354 | 2,173 | 1,181 |

| Luxemburg | 1,181 | 22,378 | 303 |

| Total | 924,101 | 493,214 | 430,887 |

Source: National Statistics Institute, 2007 Municipal Register.

Table 2. Educational level among EU-14 immigrants by area of residence

| (%) | Andalusia | Balearics | Canaries | Catalonia | Madrid | South-East | Rest | Total |

| Primary | 34 | 21 | 26 | 22 | 12 | 34 | 54 | 31 |

| Secondary | 29 | 45 | 49 | 33 | 25 | 42 | 23 | 35 |

| University | 32 | 31 | 21 | 40 | 53 | 20 | 17 | 29 |

| N/A | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 5 |

| Total | – | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

Table 3. Professional status among EU-14 immigrants by area of residence

| (%) | Andalusia | Balearics | Canaries | Catalonia | Madrid | South-East | Rest | Total |

| Employer | 10 | 21 | 14 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 8 |

| Self-employed | 25 | 25 | 32 | 30 | 11 | 30 | 15 | 24 |

| Family help | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public salary-earner | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 4 |

| Private salary-earner | 65 | 48 | 51 | 62 | 79 | 60 | 74 | 64 |

| Other | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

Table 4. Occupation breakdown among EU-14 immigrants by area of residence

| (%) | Andalusia | Balearics | Canaries | Catalonia | Madrid | South-East | Rest | Total |

| Business management | 12 | 24 | 26 | 25 | 12 | 15 | 6 | 16 |

| Technical experts and professionals | 11 | 4 | 11 | 16 | 38 | 19 | 19 | 18 |

| Aux. professionals & technicians | 34 | 24 | 3 | 16 | 16 | 17 | 6 | 16 |

| Administrative employees | 9 | 15 | 11 | 10 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Services employees | 7 | 10 | 17 | 7 | 20 | 18 | 9 | 12 |

| Skilled workers in agriculture/fishing | 0 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Craftsmen and skilled workers | 10 | 11 | 15 | 9 | 8 | 12 | 31 | 14 |

| Machinery workers and installers | 9 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 9 | 10 | 6 |

| Unskilled workers | 8 | 9 | 13 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 17 | 9 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

Table 5. Age groups (five year bands) by origin

| (%) | EU-14 | Natives | Rest of Europe | Africans | Latin Americans | Other |

| 0-4 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 13 |

| 5-9 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| 10-15 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 |

| 16-19 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 2 | 8 | 4 |

| 20-24 | 2 | 6 | 11 | 9 | 8 | 5 |

| 25-24 | 6 | 8 | 17 | 13 | 15 | 8 |

| 30-34 | 10 | 8 | 20 | 20 | 19 | 12 |

| 35-39 | 8 | 8 | 15 | 18 | 14 | 11 |

| 40-44 | 14 | 8 | 8 | 12 | 10 | 15 |

| 45-49 | 9 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 7 |

| 50-54 | 8 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| 55-59 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| 60-64 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| 65 or more | 21 | 16 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

Table 6. Educational level by origin

| (%) | EU-14 | Natives | Rest of Europe | Africa | Latin America | Other | Total |

| Primary | 31 | 49 | 32 | 67 | 41 | 31 | 48 |

| Secondary | 35 | 21 | 45 | 20 | 36 | 25 | 22 |

| University | 29 | 14 | 15 | 6 | 12 | 19 | 14 |

| N/A | 5 | 16 | 8 | 6 | 11 | 24 | 16 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

Table 7. Employment status among active population by origin

| (%) | EU-14 | Natives | Rest of Europe | Africa | Latin America | Other | Total |

| Employed | 90 | 91 | 85 | 82 | 88 | 93 | 91 |

| Looking for work | 10 | 9 | 15 | 18 | 12 | 7 | 9 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

Table 8. Professional status by origin

| (%) | EU-14 | Natives | Rest of Europe | Africa | Latin America | Other | Total |

| Employer | 8 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Self-employed | 24 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 15 | 11 |

| Cooperative | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Family help | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Public salary-earner | 4 | 17 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 14 |

| Private salary-earner | 64 | 65 | 90 | 86 | 91 | 67 | 68 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

Table 9. Occupation sector by origin

| (%) | EU-14 | Natives | Rest of Europe | Africa | Latin America | Other | Total |

| Agriculture and fishing | 3 | 4 | 10 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 4 |

| Mining, food and textile | 4 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| Other industries | 4 | 6 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 |

| Machinery manufacture | 5 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| Construction, water, gas and electricity | 13 | 12 | 30 | 21 | 26 | 10 | 13 |

| Commerce and hotels and catering | 26 | 22 | 24 | 28 | 23 | 33 | 23 |

| Transport and finance | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 6 |

| Real estate, IT, research, public administration | 18 | 13 | 6 | 9 | 5 | 13 | 13 |

| Education and health | 13 | 20 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 18 |

| Other | 8 | 6 | 7 | 21 | 18 | 8 | 8 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

Table 10. Occupation by origin

| (%) | EU-14 | Natives | Rest of Europe | Africa | Latin America | Other | Total |

| Armed Forces | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Management of companies and public administrations | 16 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 12 | 8 |

| Scientific experts and professionals and intellectuals | 18 | 14 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 14 | 12 |

| Supporting technical experts and professionals | 16 | 13 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 13 | 12 |

| Administrative employees | 7 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 9 |

| Restaurant, personal and protection services personnel, and sales personnel | 12 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 22 | 24 | 15 |

| Skilled workers in agriculture and fishing | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Craftsmen and skilled personnel in manufacturing industries, construction and mining | 14 | 15 | 29 | 29 | 20 | 12 | 16 |

| Operators of installations and machinery, and assembly workers | 6 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 9 |

| Unskilled workers | 9 | 11 | 34 | 35 | 38 | 13 | 15 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source: EPA 4Q07 and own research.

[1]I am grateful for the help in preparing this Working Paper to the embassies in Spain of a number of European countries, to a number of qualified foreign experts, to Spanish technical experts from the Education Ministry and regional governments, as well as coastal municipal governments, and to José de la Paz and Juan Ignacio Martínez Pastor.I am particularly grateful to Luis Garrido, who, with his indefatigable enthusiasm and generosity, did so much more than simply comment on the text, and who drew up several of the tables included herein.

[2] See, for example, Teresa Gómez (1989),‘Europeos en España. Principales características de los flujos de inmigrantes procedentes de la CEE’,Revista de Economía y Sociología del Trabajo, no. 4-5, pp. 113-123.

[3] This is probably because Portuguese immigration is almost entirely work-based and they have to register with the Interior Ministry before they can register with the Social Security.

[4] Diego López de Vera (1995),‘La inmigración en España a finales del Siglo XX. Los que vienen a trabajar y los que vienen a descansar’,Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológica, nr 71-72, p. 225-245.

[5] For more information on European pensioners residing in Spain, see the works by Vicente Rodríguez, especially Vicente Rodríguez Rodríguez, María Ángeles Casado Díaz& Andreas Huber (2005),La migración de europeos retirados en España,CSIC (UPC), Madrid.

[6] The data compiled for this year’s National Immigration Survey (Encuesta Nacional de Inmigración – 2008) conducted by the Statistics Institute (Instituto Nacional de Estadística – INE) will allow this comparison.

[7] Mónica Méndez (2004),‘Derecho de voto y ciudadanía. Un análisis de la movilización de los residentes europeos en las elecciones de 1999 y 2003’, a working paper presented at the 4thCongress on Immigration in Spain, in Gerona, available on CD-Rom.

[8] This law (Ley Reguladora de la Actividad Urbanística de la Comunidad Valenciana), of 2004, allowed the administration and private developers of Immediate Action Plans (Planes de Actuación Inmediata – PAI) to force the owners of properties to accept these plans, in many cases forfeiting much of their land so as to enable the construction of new homes, roadways or common areas for the new developments. Many owners of chalets with a medium-sized plot of land were part-expropriated and soon found themselves surrounded by brand new houses. The law was denounced before all political authorities in Valencia and Spain and before the European Parliament and Commission. Pressure from the latter two bodies forced the Valencia regional government to change the law, which became known as the Planning Act (Ley Urbanística, 2006), but the protests continued and the Commission eventually denounced the Spanish state before the Court of Justice. The Valencia regional government is now in the process of reforming the new law.

[9] See Raúl Lardiés Bosque & Marisol Castro Romero (2002), ‘Inmigración extranjera en Cataluña:las nuevas motivaciones de los ciudadanos europeos para el desplazamiento y la atracción del turismo’,Scripta Nova, nr 119, August.

[10] The responsibility for ensuring that Spaniards learn English should not fall solely to the education system: public television should follow the example of other European countries which systematically broadcast films and series in English with subtitles.