Also available the Spanish version: El conflicto independentista en Cataluña.

Further information at the web The independence conflict in Catalonia.

Previous dossier: Catalonia’s independence bid: how did we get here? What is the European dimension? What next? (Updated: 19 January 2018).

The territorial pluralism of Spain and the “State of Autonomies”

- The complexity of the centre and the periphery when it comes to territorial matters and identity is a distinctive feature of the Spanish political system. This feature is shared with other plural democracies such as Belgium, Canada and the UK (and, to a lesser extent, Italy and Switzerland).

- Nonetheless, Spain is one of the few states in Europe that has successfully preserved its national integrity. In contrast to the rest of the continent, Spain’s borders have remained unaltered for five centuries and there has not been a single territorial change in the last two centuries (colonial possessions aside).

- The reasons for the paradoxical balance between preserving the country’s integrity, on the one hand, and power and identity struggles between the centre and the periphery, on the other, are bound up with the country’s history and its institutions, interests and dominant political ideas.

- Countries with high levels of ethnic and territorial pluralism are common outside the West. In Europe, however, the paradigm of the nation state has prevailed. The tendency has been for either the assimilation of alternative peripheral identities (not just minorities), along the lines of France, or cleaving them from the existing state and creating a new one. Mixed identities and decentralised power are rare.

- In contrast, this small group of non-homogeneous European states is characterised by their different individual histories, with all the diversity and complexity this entails. In the case of Spain, there are a number of main features:

- Its origin and formation centuries ago was only partly based on identity and was more religious than proto-national.

- Spain successfully projected itself as an empire and subsequently remained relatively isolated from the modern conflicts that shaped the continent.

- The state experienced early and effective construction between the 15th and 18th centuries. The modern national construction came much later in the 19th and 20th centuries and with much more upheaval. Both processes took place under the leadership of Castile, which occupied the central position and the dominant language.

- Nonetheless, the centre never had the strength to impose a process of homogenisation. Throughout this period, it has faced competition from alternative identities in peripheral territories, the most significant being Catalonia and the Basque Country, both positioned near the arteries of European development.

- We should also note that, just as the map of Spain has remained intact for centuries, the contours marking out the strong individual personalities of certain Spanish territories have persisted (in the case of Catalonia, these boundaries have gone unchanged since the second half of the 17th century). This is in contrast to France, Germany and Italy, where the regional configurations have undergone relatively frequent changes.

- Catalonia and the Basque Country were never kingdoms or independent states. The majority of what is now Catalonia was the County of Barcelona in the Early Middle Ages, before becoming part of the Crown (not the Kingdom) of Aragon in 1162 and then part of the Spanish Monarchy from 1479. The mediaeval organs of self-government, which came under a brief spell of French sovereignty in 1641, were abolished in 1714 following the War of Spanish Succession, when Spain ceased to be a composite monarchy and became an absolutist unitary kingdom.

- Despite their initial conservative bias (opposed to Jacobin liberalism), nationalism in the Basque Country and Catalonia subsequently became associated with the fight against the authoritarian and military tendencies that often dominated the centre.

- Catalan nationalism rose to prominence at the start of the 20th century, driven by the dual base of the rural population and a modernising middle class. The region simultaneously experienced two dynamic processes: the cultural renaixença and an industrialisation marked by its privileged geographic location. These occurred in the context of a weak Spanish State but with a large protected internal market, favouring the first major waves of migrations to Catalonia, which led to the current pluralist nature of Catalan society.

- Regional self-rule was closely linked to freedom in the 20th century. The autonomy enjoyed by Catalonia during periods of democracy (1914-23 and 1931-39) was rescinded by the dictatorships of Primo de Rivera (1923-30) and Franco (1939-75). The Franco regime recentralised power and was initially extremely hostile to the Catalan language, despite some tolerance of its use socially from the 1960s, coinciding with strong economic development.

- After the transition to democracy, the Constitution of 1978, which enjoyed overwhelming support throughout Spain and especially in Catalonia, decreed that sovereignty rested in the hands of the Spanish people as a whole, adding that regions and ‘nationalities’ had the right to political autonomy. Two of the seven members of the committee that drafted the Constitution currently in force were Catalans.

Figure 3. Constitutional referendum of 1978

| Electors | Turnout | YES votes | NO votes | Blank/spoilt | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPAIN | 26,632,180 | 67.1% | 87.9% | 7.8% | 4.2% |

| Catalonia | 4,398,173 | 67.9% | 90.5% | 4.6% | 4.9% |

Source: Ministry of the Interior.

- Although the desire for self-rule was widespread throughout almost all of Spain, political forces in Catalonia (nationalist and federalist) played an especially strong role in the promotion and development of the ‘State of the Autonomies’. The Catalan and Basque Statutes (1979) were the first to be approved in referendums and received strong public backing (88.15% in the case of Catalonia).

- Between 1980 and 1983, the other regions of Spain also created Statutes of Autonomy with significant powers (albeit less than in the Basque Country and Catalonia)..

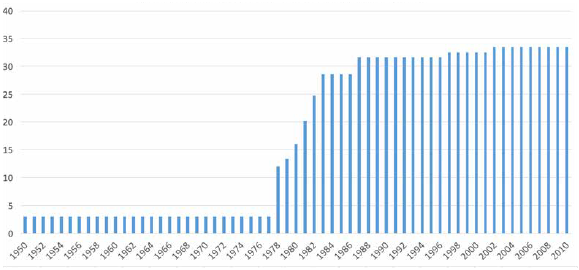

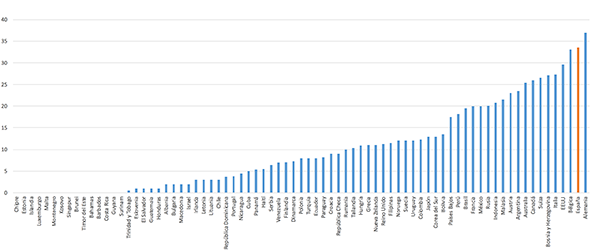

- In contrast to the slow and timid process of regional devolution in the United Kingdom, Italy and, later on, France, the territorial organisation of Spain passed from hyper- centralisation to a de facto federation in just five years. After Belgium, Spain is the European country that has most decentralised its state structure in the last half-century.

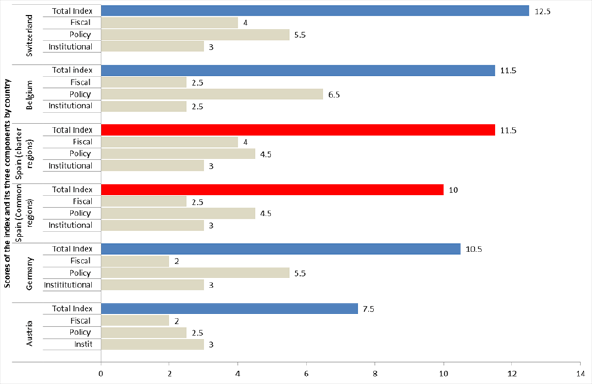

- According to the Regional Authority Index (RAI), Spain’s State of Autonomies currently makes it the second most decentralised state in the world, with only Germany ahead.

- Other regional self-rule indexes (eg, Dardanelli, 2019) even rank the power enjoyed by the Spanish autonomous communities as equal to or greater than German Länder (and only slightly below Swiss cantons, Belgian regions and specific cases like the Faroe Islands in Denmark).

- The powers of the autonomous regions are not only broad from the institutional and legal perspectives (guaranteed by the Constitutional Court) but they effectively translate into a different political system and wide-ranging public spending.

- Nonetheless, certain features of the model of territorial organisation could have limited real autonomy. The central power’s use of funding and basic legislation generates conflicts and might even lead to the erosion of regional powers. The ineffectiveness of the Senate as a territorial chamber also means the high level of self-government is barely reflected in the participation of autonomous communities in state decisions (shared rule).

- Despite the theoretical scarcity of shared rule, Catalonia and the Basque Country have developed an indirect form of power to influence governance of the state through sub- state nationalist parties in the central parliament.

- This indirect mechanism for exercising power, which is highly imperfect because it lies not in institutions but in specific parties, has created grievances with the rest of Spain, strengthening the asymmetry of informal power in certain areas in favour of the Basque Country, Catalonia and, to a lesser extent, other large regions.

- In terms of funding, however, Catalonia’s revenue system is similar to the other autonomous communities that are subject to the standard régimen común arrangement, whereby tax revenue is collected by the Spanish state. Yet while its contribution is roughly proportional to its wealth and funding is in line with its population, certain leaders aspire to the régimen de concierto system, in which revenue is collected by decentralised government and a proportion paid to central government and which applies to the Basque Country and Navarra, also wealthy but which contribute less.