Abstract

This paper aims to summarise and present the main proposals of the Spanish White Book on Tax Reform in the environmental domain, a particularly important chapter, amounting to around 15% of its total content. It attracted significant attention from the public due to its numerous and ambitious proposals, together with their detailed assessment. The White Book might be useful for an international audience, as Spain shares with other advanced countries many environmental problems and challenges associated with the ecological transition and has a very similar regulatory and tax structure. Moreover, the environmental and distributional conclusions of the environmental chapter are particularly relevant at times of energy and climate crises.

Introduction

In April 2021 the Spanish Government commissioned a group of 17 experts, mostly professors of economics and law, to prepare a White Book (WB) on tax reform for the necessary adaptation of the Spanish tax system to the economic reality of the 21st century. To this end, the experts were asked to carry out an analysis of the optimal tax system in a broad sense, evaluating aspects such as the sufficiency, equity and efficiency of the different sources of public revenue. Specific analyses were also requested on environmental taxation, corporate taxation, taxation of the digital economy and emerging activities, and wealth taxation. The Government included the preparation of the WB, which was delivered in early March 2022 (CPELBRT, 2022), within its plan and commitments to receive the significant funding from the EU Recovery and Resilience Facility to mitigate the economic and social impacts associated to COVID.

The WB is fully available online but unfortunately it does not have an English version. Therefore, this working paper aims to summarise and present the main fiscal proposals of the WB in the environmental arena. This is a particularly important chapter in the WB, occupying around 15% of its contents and having received special attention from the media due to its numerous and ambitious proposals together with their detailed assessment. The WB was subscribed jointly by all the members of the committee, who, however, were distributed in teams to deal with the various thematic areas. As one of the experts who participated in the preparation of the environmental chapter, I have attempted to provide a reliable summary of the main contributions in this field, although I am obviously responsible for the selection of contents (given the limited space available) and for certain personal appreciations (mainly in the introduction and conclusions).

Of course, this is not the first white paper to be produced on these matters. In Spain the most recent precedent is the so-called Lagares Report (2014) on the reform of the Spanish tax system, which incorporated detailed reflections in the environmental field. Other Spanish expert commissions on local, regional or energy transition taxation have also proposed changes in this field. However, the environmental chapter of this WB differs from the preceding reports in its greater detail and, above all, in the precise quantification of many of its proposals, in addition, of course, to being included as a Spanish commitment with the European Commission. The work of other international governmental commissions on environmental taxation is more limited. The white paper echoes the recent work of the New Zealand tax reform commission and, of course, the very influential Mirrlees Report (2011). The latter, however, has a more limited degree of detail in its three chapters devoted to these issues (environmental, climate change and transport taxation).

In any case, it is not only the detailed and extensive exploration of the role of environmental taxation in solving Spain’s main environmental challenges that might make this working paper interesting for an international audience. Spain shares with other advanced countries many environmental problems and challenges associated with the ecological transition and has a very similar regulatory and tax structure (highly harmonised in the case of the EU). Therefore, I believe that the conclusions presented here can be highly useful beyond Spain’s borders.

The working paper is organised in five sections, including this introduction. The second section contains the chapter’s foundations and its diagnosis of the Spanish tax system in this domain. What follows is a concise presentation of the principles and guidelines that inform the WB’s environmental proposals. The fourth section details the main proposals and the results of their illustrative assessment in four main areas: electrification, transport, circularity and water. Finally, the last section of this paper presents the main environmental and distributional messages from the WB and highlights its relevance nine months later, in the midst of intense and simultaneous energy and climate crises.

Environmental taxation in theory and practice

Foundations

Environmental taxes are levies that aim to foster changes in the behaviour and stock (equipment) of economic agents (consumers, producers) that can lead to a reduction of emissions and/or the use of material resources, thus achieving lower environmental impacts. For this purpose, it would be necessary for the environmental tax rates and base to be related to the environmental damage or to contribute to achieving pre-established environmental objectives. Since the taxes are designed to address negative externalities of economic activities, it would thus be desirable for their tax rate to be close to the marginal external cost of emissions, consumption or production. However, as environmental policies are usually set on the basis of emission reduction targets in the real world, environmental taxes might also be useful in this setting due to their ability to attain these targets.

Environmental taxes have several advantages that make them a preferred option for economists specialised in environmental policy, explaining the academic insistence on their use and the interest of many international organisations and think tanks. They are instruments that aim to ‘get the prices right’ by complying with the ‘polluter pays principle’, leading agents to make appropriate decisions. Since there is usually a great heterogeneity among those causing environmental damage, as well as problems of asymmetric information on costs and emission reduction possibilities between regulator and polluters, environmental taxes achieve improvements at a minimum cost because, compared with other policy alternatives, they allow agents to adapt and thus lead them to automatically reveal their costs and possibilities of reducing environmental impacts (Fullerton et al., 2010). In any case, these properties apply only when all those causing the environmental problem face the price signal with the same intensity, which recommends avoiding sectoral exemptions and tax reductions.

Considering the magnitude of the efforts required and the short time frames when dealing with many environmental problems, cost-efficiency makes environmental taxes a crucial alternative for the transition to climate neutrality and the reduction of environmental impacts and natural resource use, while also limiting the potential competitiveness and distributional impacts (in absolute terms). These instruments also facilitate the development and adoption of clean technologies by making them more competitive due to the burdens imposed on dirty alternatives, thus incentivising equipment change both at the individual and business levels, which is imperative for ecological transition.

It is also important to stress the salience that is usually associated with taxation (Rivers & Schaufele, 2015). Unlike other policy alternatives, environmental taxes generally bring about a clearer view of the costs and their distribution by groups of citizens or by sectors, which facilitates the definition of compensatory measures to protect competitiveness or possible negative distributional impacts. Moreover, there is growing academic evidence that the higher the salience of a policy instrument, the stronger the reaction of agents and thus its environmental effectiveness.

The growing concerns regarding the costs of ecological transition demands that special attention be paid to the distributional and competitiveness impacts of environmental taxes, and to compensatory alternatives to mitigate them. Again, environmental taxes have the advantage over other regulatory alternatives in that they generate public revenues that can be used to compensate those affected (Pizer & Sexton, 2019). These compensations might be carried out by modifying the tax structure applied to certain agents (exemptions, etc), or through targeted and limited transfers to certain sectors or socio-economic groups, which would be better as they do not interfere with the desired incentive effects. These transfers can be complemented with subsidies to facilitate a change of polluting equipment, thus reducing distributional and competitiveness impacts of environmental taxes in the medium and long terms.

In any case, environmental taxation is likely to be a necessary but not sufficient instrument for ecological transition, and other environmental policy instruments such as emissions markets, subsidies, conventional regulations or information approaches cannot be ignored. In this context, it is essential to seek synergies between the different regulatory alternatives and avoid negative interactions between them (OECD, 2015). A package of policy instruments that favours clean technological development is particularly crucial: for instance, combining the incentive action of environmental taxes with conventional alternatives such as subsidies to R&D and certain investments.

Additionally, the evaluation of environmental taxes is imperative. This assessment should contemplate several criteria, including their environmental effectiveness (the extent to which they provide incentives to reduce emissions or resource use in the short and long terms), their socio-economic impacts and their revenue-raising capacity and distribution of burden by household group and economic sector (Gago et al., 2021a). In general, the academic literature shows that environmental taxes achieve positive environmental impacts, especially when compared with what would have happened without their introduction, have high cost-effectiveness, generate distributional impacts that strongly depend on the context of application and the existence of compensatory measures, and do not have significant effects on competitiveness. However, they face significant barriers, as they are unpopular measures and subject to lobbying by industry (see Gago et al., 2014).

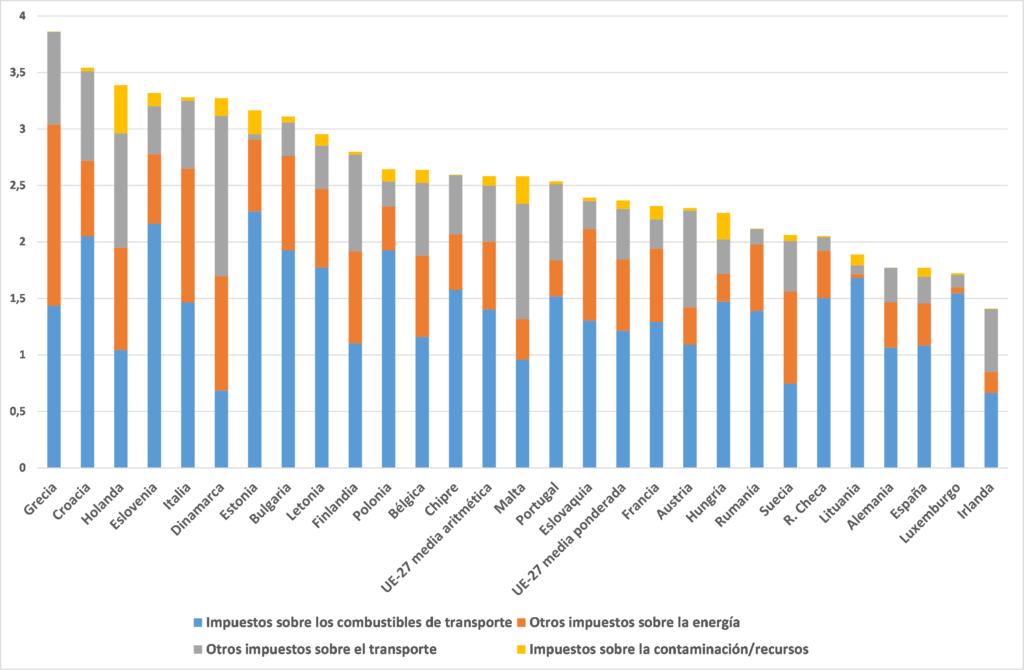

Spain in the international context

Environmental taxation plays a relevant role in tax systems around the globe, with revenues in 2019 accounting for 1.52% of GDP and 5.03% of tax revenue in the OECD (2021), as well as 2.4% of GDP and 5.9% of tax revenue in the EU-27. Energy taxes are the main source of environmental revenues in the EU-27 (78%), especially those levied on transport fuels, while other transport taxes account for 19% of revenues and pollution, while resource taxes account for only 3% (European Commission, 2021b).

The WB pays particular attention to the existing academic evidence for Spain, generally through ex-ante simulations of the effects of different environmental taxes. The sizeable literature generally shows a significant effectiveness in correcting the environmental problem, with limited economic and distributional impacts (Gago et al., 2021b). Furthermore, there is evidence of the social acceptance of these figures (IEF, 2021), although there are divergences between different taxes and, in general, citizens are in favour of proposals with a clear environmental rationale and distributional compensations. However, the Spanish experience with these taxes shows a limited number of applications as well as –in many cases– a deficient choice and tax design, which places the country at the bottom of the EU classification in the use of these taxes (Figure 1). Indeed, many environmental problems, polluting activities or sectors are not covered, and there is a use of tax rates that do not adequately reflect damages or contribute to the attainment of Spanish commitments in the field. Likewise, there is excessive administrative complexity, scant linkage with environmental problems to correct certain tax bases and an unequal and uncoordinated use of environmental taxes at different jurisdictional levels.

Figure 1. Environmental revenue in relation to GDP, 2019

These problems have been repeatedly pointed out by the European Commission and many other international organisations, calling on successive Spanish governments to adopt a more proactive attitude to environmental taxation but with little result so far. Additionally, in recent years various official expert groups have been asked to provide a diagnosis of the situation and to formulate proposals in this area, showing up the lesser development, design deficiencies and scant progress achieved during the last decades. Undoubtedly, this has negatively affected the ability of Spanish public policies to deal with the damages and commitments associated with growing environmental problems and is likely to require more intensive and extensive efforts in the field of environmental taxation.

Principles and guidelines for Spanish environmental tax reform

Given the above-mentioned need to address the quantitative and qualitative problems of environmental taxation in Spain, several principles have guided the work of the expert group to underpin and guide the specific proposals of the WB.

Environmental rationality

Environmental taxes should be understood as the necessary response to the high and increasing vulnerabilities and impacts seen in Spain. Indeed, Spain is one of the advanced countries most affected by climate change, which has important implications due to the dependence of many economic activities on environmental conditions and natural resources (Eckstein et al., 2020). Local pollution is also a persistent problem and the source of major human health problems in most urban areas, while Spanish biodiversity is threatened by human-induced disruptions.

This is the main context for deciding which environmental taxes to prioritise and the intensity of their application. Figure 2 shows some of the environmental targets to which Spain has legally committed itself, generally as a consequence of EU policies and strategies, to allowing a roadmap to be drawn up showing the priorities and timing of the necessary reforms. In particular, it highlights the need for action on greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, especially in the so-called diffuse sectors (not subject to the EU emissions trading system or ETS), and on other relevant pollutants that are generated by transport and agriculture. There are also significant discrepancies between the commitments adopted and the current situation in solid waste, while in water there is a clear inability to recover the costs associated to its use.

Low Spanish environmental taxes will lead to higher-than-necessary costs to address the growing environmental problems faced by the country, which is particularly worrying in the case of ambitious environmental objectives to be achieved in a short time span. An intensification of environmental taxation is therefore desirable as part of an integrated and comprehensive approach, breaking with the current trend.

Figure 2. Spain’s environmental commitments

| Environmental problem / Reference year | Target | Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Greenhouse Gas Emissions (GHG) / 1990 | -23% in 2030 | +8.5% (2019) |

| 1b. GHG emissions diffuse sectors/2005 | -26% in 2030 (-37.7% in 2030, Fit for 55) | -15.1% (2019) |

| 2. Emissions of Nitrogen Oxides (NOx) / 2005 | -41% between 2020-29 -62% from 2030 | -50.3% (2019) |

| 3. Emissions of Volatile Organic Compounds other than Methane (NMVOC) / 2005 | -22% between 2020-29 -39% from 2030 | -23.3% (2019) |

| 4. Ammonia (NH3) Emissions / 2005 | -3% between 2020-29 -16% from 2030 | -2.8% (2019) |

| 5. Particulate Matter 2.5 (PM2,5) Emissions / 2005 | -15% between 2020-29 -50% from 2030 | -8.6% (2019) |

| 6. Energy efficiency (Mtoe) | Primary energy: 122.6 (2020); 98.5 (2030) Final Energy: 87.23 (2020); 73.60 (2030) | Primary energy: 120.75 (2019) Final energy: 86,30 (2019) |

| 7. Weight of waste produced / 2010 | -10% in 2020 -15% by 2030 | -8.1%* (2018) -6.9%** (2018) |

| 8. Household and similar wastes destined for preparation for reuse and recycling | 50% by 2020 | 35%*** (2018) |

| 9. Non-hazardous construction wastes destined for preparation for reuse and recycling | 70% in 2020 | 47%**** (2018) |

| 10. Recovery of the costs of water-related services | 100% | 67,9% |

Sources: CPELBRF (2022) from MITECO, Inventario Nacional de Emisiones a la Atmósfera; INE, Estadísticas sobre Recogida y Tratamiento de Residuos; MITECO, Memoria Anual de Generación y Gestión de Residuos; European Commission, Commission Assessment for Spain’s NECP; Eurostat, Energy Efficiency; and MITECO, Síntesis de los Planes Hidrológicos Españoles. WFD Second Cycle (2015-2021).

Coordination and complementarity within the regulatory context

Particular attention needs to be paid to the regulatory context to ensure the effectiveness and proportionality of the proposals in practice. In this respect, the EU has set ambitious targets in its 2050 decarbonisation strategy, in addition to considerable legislation in the environmental field that must be transposed by member states, so that tax proposals should consider and start from this context in order to determine their characteristics and ambition, also avoiding possible negative interactions with other environmental policy instruments.

Realistic proposals should therefore consider EU energy-climate packages, which have been establishing objectives in various policy areas and instruments since the beginning of the 21st century. In particular, the Energy Taxation Directive (ETD) is highly relevant, since the energy-environmental taxation of EU countries is harmonised in scope of application, in its essential elements and in general design. The proposal for a new ETD (European Commission, 2021a), presented in July 2021 as part of the Fit for 55 package, focuses on the energy component to promote energy efficiency, leaving GHG pricing to a future emissions trading market for transport and buildings. In addition, it incorporates a considerable reduction of the favourable tax treatments of the current directive and explicitly considers distributional impacts and their compensation.

Likewise, the existence of environmental problems of a territorial nature justifies the tax role of sub-national administrations in this area, although the existence of a high degree of heterogeneity in the introduction, design and application of these taxes by Spanish regions (Comunidades Autónomas, CCAA) may jeopardise compliance with environmental objectives, as well as introduce undesirable socio-economic distortions. In this context, the WB considers it necessary to ensure greater coordination and cooperation between administrations to guarantee an appropriate and effective use of environmental taxes.

Effectiveness

This is a crucial principle, as environmental taxes should have environmental and design conditions that justify their introduction within fiscal and environmental protection policies. Thus, the WB proposals generally respond to the following premises: (a) extension of tax coverage to sectors and activities that generate negative environmental impacts and reduction of favourable tax treatments; (b) priority search for changes in behaviour and investments in clean technologies; (c) focus on areas with numerous heterogeneous agents to take advantage of the comparative advantages of taxes in terms of minimising costs; (d) adequate integration in the environmental regulatory framework; (e) promotion of synergies and reduced negative interactions with other policy instruments; (f) adequate jurisdictional allocation and coordination; and (g)contribution to the development and deployment of technologies that facilitate ecological transition.

Distributional considerations

Environmental taxes will have significant socio-economic impacts for many households and firms in any credible ecological transition, so many of the proposals explicitly consider their distributional and competitiveness impacts and propose mechanisms for their compensation. These offsets will be particularly desirable when taxes affect essential goods and services and when they represent an important part of household budgets. In any case, the fundamental objective of such taxes is to reduce environmental degradation, and their introduction should not be limited by possible regressive effects.

In this context, the WB generally chooses a gradual approach so that impacts are minimised and companies and households causing environmental problems are able to adapt at affordable costs. In addition, it is essential that distributional or competitiveness offsets do not affect the incentives for environmental improvement introduced by taxes. Compensations should not be generalised, but rather focus on those most affected and vulnerable. Moreover, they should preferably be channelled through direct cash transfers, personal income tax offsets or specific bonuses associated with certain consumption, as well as subsidies for equipment replacement and for the development and deployment of clean technologies.

Priority areas for action

Following the spirit of tax reform (vs tax design) followed in the WB and the above considerations, the environmental tax proposals are classified in four general areas:

- Sustainable electrification: electricity should play a key role in the transition to a low-carbon economy because, unlike other sectors, it has mature renewable energy alternatives. Therefore, environmental taxation should contribute to electrification, without forgetting the necessary energy efficiency signals and the importance of taxing the eventual environmental damages associated to electricity generation.

- Mobility compatible with ecological transition: the transport sector is the main cause of Spanish GHG emissions and of recurrent local pollution problems in many cities, so it is necessary to intensify and extend environmental taxation levied on vehicles and fuels, favouring less-polluting transport modes and encouraging the development and adoption of clean technologies.

- Increasing circularity: this is a cross-cutting concept that seeks to optimise the use of resources, although it is usually identified with proper waste management. Spain needs to make faster progress in this area, through a more decisive use of environmental taxation, in line with the new EU strategies.

- Incorporating environmental costs associated with water use: a key resource for many economic activities in Spain, water is suffering from increasing scarcity due to both the effects of climate change and excessive and inefficient use. Environmental taxation should therefore help to ensure that the price of water reflects all environmental costs and its increasing scarcity.

The proposals of the WB are comprehensively evaluated following the criteria indicated in section (2.1), particularly on their environmental effectiveness, revenue capabilities and distributional impacts. To this end, when appropriate data and models are available, ad hoc simulations are carried out; otherwise, the academic evidence available on comparable instruments for Spain or neighbouring countries is extrapolated. In any case, more detailed empirical explorations are required before their introduction in the real world. Likewise, the WB recommends carrying out ex-post evaluations of the eventually implemented proposals to foster improvements in their design and application. Simulations are generally carried out using 2019 data, using price elasticities from the literature to calculate the revenue and emissions effects of the various proposals. The distributional impacts of the reforms on households are determined using data from the Household Budget Survey (INE, 2021b), using total household expenditure as the income variable. With the new prices derived from the tax changes, the impacts are calculated from the price elasticities considered, adjusting the results with factors obtained from the Living Conditions Survey (INE, 2021a).

Simulations are generally carried out using 2019 data, using price elasticities from the literature to calculate the revenue and emissions effects of the various proposals. The distributional impacts of the reforms on households are determined using data from the Household Budget Survey (INE, 2021b), using total household expenditure as the income variable. With the new prices derived from the tax changes, the impacts are calculated from the price elasticities considered, adjusting the results with factors obtained from the Living Conditions Survey (INE, 2021a).

Proposals for the reform of environmental taxation in Spain

As indicated, the WB’s environmental tax proposals are grouped in four general sections that incorporate a general reflection on the usefulness of taxes to deal with the specific environmental problem, a description of existing taxes in the area in Spain and a summary of the available empirical literature. This procedure provides a basis for the proposals and their evaluation, as shown in the following subsections.

Sustainable electrification

As pointed out, the availability and growing deployment of mature renewable technologies in the electricity sector makes this sector key to the ecological transition, particularly in decarbonisation. To enable the transition to a low-carbon economy, the electrification of other sectors in which the development of renewable energies is limited, such as transport, will be essential. Environmental taxation should favour this process by differentiating energy sources according to their environmental profile, promoting technological development and investments that enable widespread electrification. To achieve this, the environmental taxes levied on electricity in its different phases (generation, distribution and consumption) should be reformed to align them with three fundamental objectives for the ecological transition: electrification (replacing fossil fuels with renewable electricity); promoting energy efficiency; and reducing the negative environmental impacts associated with electricity generation.

A major environmental impact of the Spanish electricity sector derives from its GHG emissions, although they are already subject to the EU ETS so there is no scope for additional pricing policies. Additional environmental impacts are associated to the emissions of other atmospheric pollutants, to the effects of electricity generation facilities on ecosystems, and to the management of radioactive waste and decommissioning of nuclear capacity. Environmental taxation can play a role in reducing environmental impacts, where the conditions for its appropriate application exist, and should particularly promote higher energy efficiency, thus helping reduce the overall environmental impacts associated with electricity generation.

At present, the Spanish government levies different taxes on electricity generation, including the tax on the value of electricity production (IVPEE), which is levied on the production and incorporation of electricity into the system, taxes on the production and storage of radioactive waste, and the tax on the use of inland waters for electricity production, which is levied on the value of the hydroelectric energy produced. There are also several regional taxes on electricity generation and distribution (taxes on installations, water reservoirs, atmospheric emissions, wind energy and electricity generation). Taxes on electricity consumption include the (harmonised) excise tax on electricity (IEE) and VAT at the general rate.[1] As a result of these figures, the tax burden on electricity in Spain has traditionally been higher than the EU average for households, but lower for industry (Eurostat, 2021a).

In this context, the specific proposals to favour the ecological transition in the electricity sector would be the suppression of the IVPEE, the modification of the IEE, the introduction of measures to improve the design and effectiveness of regional taxes in this area and the coverage of all costs associated with nuclear power plants.

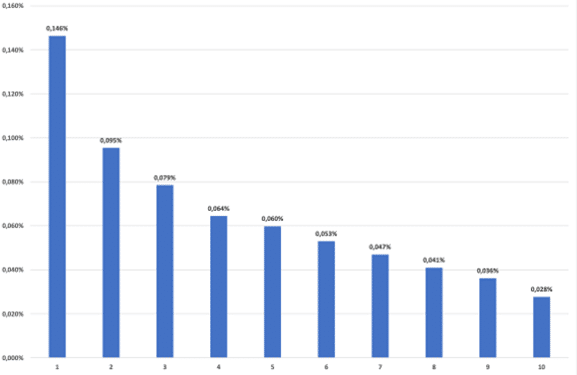

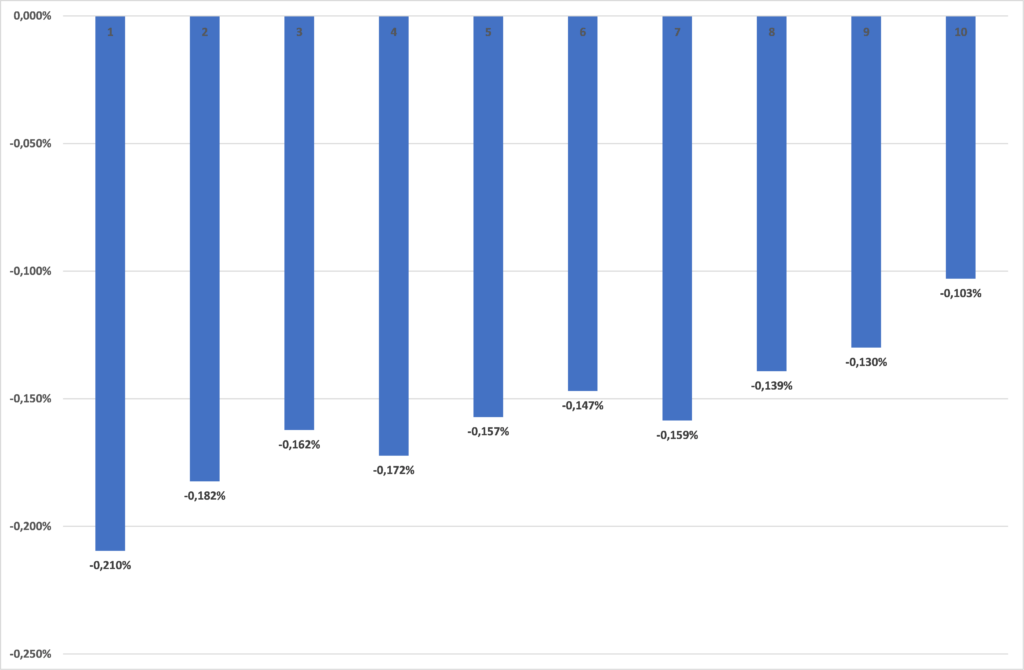

The IVPEE was introduced with the aim of reducing the pervasive electricity sector deficits and it does not promote technological change in electricity generation (as it does not discriminate between technologies according to their environmental impacts), and it hinders electrification by increasing relative electricity prices. Thus, its only environmental benefits derive from its positive effects on energy efficiency, which could also be achieved with the IEE. Using electricity consumption data from CNMC (2020), as well as electricity price data from Eurostat (2021a) and the electricity price elasticity estimated for Spain by Labandeira et al. (2016), Figure 3 shows that the proposal should lead to a significant reduction in electricity prices and an increase in emissions, as well as a significant revenue loss, but its distributional impacts on households would be progressive (Figure 4). It would thus contribute to achieving greater electrification and without distributional trade-offs or competitiveness losses.

Figure 3. Impacts on prices, consumption and revenue of the suppression of IVPEE

| Price (%) | Consumption and CO2 emissions (%) |

Variation in revenues, € mn

(% on revenues from IVPEE, IEE and VAT) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVPEE | IEE | VAT | Total | |||

| Residential electricity | -2.46 | 0.50 | -372.31 | -15.27 | -65.91 | -453.48 |

Non-residential |

-3.74 | 0.76 | -468.88 | -19.29 | – | -488.17 |

Non-residential |

-3.74 | 0.76 | -286.86 | -1.77 | – | -288.63 |

| Total | – | 0.68 | -1,128.04 | -36.32 | -65.91 | -1,230.28 |

For its part, the IEE was introduced in 1998 with the initial purpose of obtaining the necessary revenue to finance subsidies to coal mining, which explains why its tax level is well above the minimum set by the ETD. Given the need to apply comparatively lower tax rates on electricity compared to other energy products to promote electrification, it would be appropriate to reduce its tax rate to the minimum set by the new directive, as well as to establish as the taxable base the amount consumed (instead of the VAT tax base currently used) to incentivise energy efficiency and savings in a more direct way. The simulation of the effects of this measure shows similar, although slightly higher, results to those reported from the suppression of the IVPEE. Thus, the combination of both proposals would allow for a significant reduction in the price of electricity, encouraging electrification, with a progressive impact on households, although incentives for energy efficiency would be weakened, environmental impacts would slightly increase and there would be a high revenue cost for the public sector.

Figure 4. Distributional impact of the IVPEE suppression by equivalent income deciles

With respect to regional taxes affecting electricity, taxes on certain atmospheric emissions have had limited impacts due to the low tax rates implemented, as well as to the significant reduction of emissions in the sector in recent decades. In any case, the WB recommends exploring coordination devices such as that implemented by the Government of Canada (2020) on carbon pricing, which if applied in this area would lead to minimum tax levels enforced by the central government and allocation of extra-tax revenues to regions. Regional taxes levied on certain electricity generation and distribution facilities generally do not provide incentives to reduce the environmental impacts of these facilities and have had limited visibility due to their low tax rates, as well as being an obstacle to the necessary electrification process, so it would be recommendable to suppress them. In any case, it might be advisable to reform the taxes applied to hydroelectric plants to minimise the impacts associated with their operation, also incorporating the scarcity of water resources in their design.

Regarding nuclear energy, the WB recommends a reflection on the current tax and non-tax instruments that are levied on nuclear energy generation. The pursued objective would be to guarantee full coverage of the costs associated with the operation and dismantling of its facilities, as well as a proper and sustainable management of nuclear waste.

Mobility compatible with the ecological transition

The transport sector generates significant negative externalities that should be corrected by public intervention. These include GHG emissions and local pollution, but also the costs of congestion, accidents, noise or infrastructure, which together account for around 5% of GDP in developed countries (van Essen et al., 2019). To control these externalities, there are numerous regulatory options, but taxation can play a key role by incentivising behavioural changes and investments in clean technologies. Moreover, the existence of heterogeneous actors and multiple tax alternatives provides a suitable context for environmental taxation in this case. That is why environmental tax reforms should be aimed at incorporating the externalities associated with transport, facilitating compliance with environmental objectives at minimum cost, where modal shift should play a key role through incentivisation of less polluting alternatives.

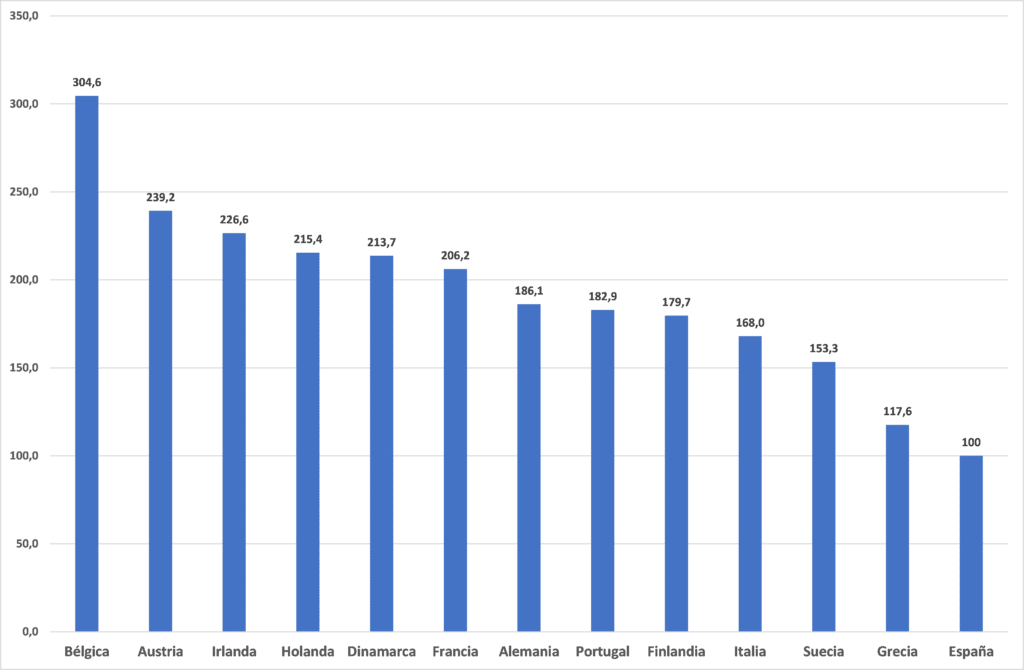

Spanish taxation on transport includes: the EU-harmonised excise tax on hydrocarbons (IEH), which is levied on motor fuels in addition to other fossil fuels such as natural gas; the tax on certain means of transport (IEDMT), which is levied on the first registration of vehicles in Spain; and the municipal tax on vehicles (IVTM), which is levied annually on the ownership of mechanical traction vehicles. In addition, Catalonia levies taxes on CO2 emissions from motor vehicles and on nitrogen emissions from aviation. In any case, Spanish taxes on motor fuels are well below the weighted EU-27 average, while taxation on vehicle purchase and ownership was also relatively low. As Figure 3 shows, once again this places Spain at the bottom of the EU ranking in terms of the total tax burden on vehicles. Moreover, the average revenue per vehicle has been significantly reduced since the mid-2000s, so that the current situation is neither justifiable nor sustainable, taking into account the importance of both the externalities associated with transport and the public revenues from this sector, and requires short-term action on existing taxes, as well as a comprehensive reform in the medium term, introducing taxes on actual vehicle use (Gago et al., 2019).

Figure 5. Average revenue per vehicle in EU countries, 2019 (Spain = 100)

Source: CPELBRT (2022).

In this context, the WB’s proposals to promote the ecological transition in the transport sector include: the reform of taxation on aviation, maritime and agricultural fuels; the introduction of a tax on airline tickets; the equalisation of taxes on motor fuels (diesel and gasoline); a general increase in taxation on hydrocarbons (motor fuels and natural gas); the reform of the IEDMT to promote a sustainable vehicle fleet; the modification of the IVTM to penalise the most polluting technologies; the creation of municipal congestion charges; the introduction of charges for the use of certain road infrastructures; and, in the medium term, the implementation of a tax on actual vehicle use that would replace most existing taxes.

Aviation, maritime transport and agriculture currently enjoy a lenient tax treatment in Spain, at least compared with most socio-economic activities, which is not sensible given the large externalities they generate and the necessary contribution of these sectors to climate change mitigation and to the reduction of other environmental externalities. In this context, the WB recommends the taxation of aviation kerosene as well as fuel oil and diesel used in maritime transport, and an increase in the tax on agricultural diesel. This would provide an incentive for a technological shift towards GHG-free fuels in these sectors. In general, such measures would have a moderate impact on fuel prices, emissions and tax revenues, although given the importance of these sectors for the Spanish economy it would be advisable to introduce the taxes gradually and to use a significant share of the additional tax revenues to encourage the development and adoption of clean technologies.

In the case of aviation, due to its strong growth in recent years and to the significant environmental costs brought about by the current technologies, it would be advisable to adopt new taxes that incorporate environmental costs into airline tickets, thus helping to moderate demand. To this end, the WB proposes the introduction of a tax on airline tickets to encourage modal shift on short journeys and to promote the development and introduction of cleaner technologies in the sector. Such a tax would generally have a progressive impact as air travel is usually associated with higher economic capacities. However, given the importance of tourism in Spain, both this levy and the kerosene tax should be carefully assessed and part of the revenues used for compensatory measures in the sector.

Road transport is one of Spain’s main sources of GHG emissions and other atmospheric pollutants and its related emissions have shown a worrying evolution in recent years, particularly in view of Spanish environmental commitments. This situation is explained, among other factors, by the low taxation applied to fuels in relation to European countries, as well as by a lower tax rate on diesel than on petrol, which does not correspond to the externalities of each fuel (in the case of diesel, actually higher per litre –see Harding, 2014–).

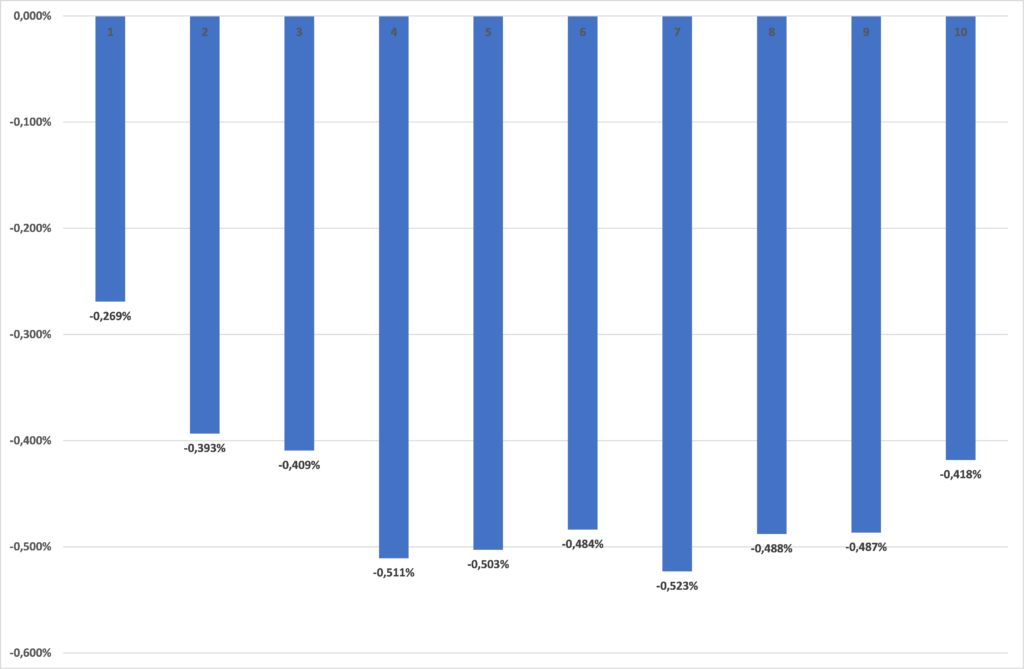

In this context, it would first be advisable to increase the excise tax rate for diesel to equal that of petrol. Using data on fuel consumption (CORES, 2021) and fuel prices (MITECO, 2021a) in Spain in 2019, as well as price elasticities from Labandeira et al. (2016), Figure 4 shows that the proposal would reduce emissions and generate significant additional revenue, although it would have a regressive impact on households. However, if the revenue is used to compensate households in the lowest five income deciles so that, on average, these households are not affected by the reform, only 8.1% of the additional revenue generated would be needed to achieve this.

Secondly, the WB recommends a general increase in the taxation of hydrocarbons, in particular on motor fuels and natural gas.[2] In this respect, besides equalising the excise duties of diesel and petrol, an additional carbon price should be contemplated together with the impacts from the National Fund for the Sustainability of the Electricity System (FNSSE).[3] In the case of natural gas, in addition to introducing the carbon price and the FNSSE, the share of the IEH could be raised to the minimum of the ETD proposal (€0.9/GJ).

Figure 6. Impacts on prices, consumption, emissions and revenue of the equalisation of gasoline and diesel tax rates

| Price (%) | Consumption (%) | CO2 emissions (%) | Additional revenues (€ mn ) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IEH | VAT | Total | |||||

| Residential diesel | 9.34 | -1.88 | -1.88 | 1,471.00 | 266.24 | 1,737.24 |

|

Non-residential |

9.82 | -1.97 | -1.97 | 884.08 | – | 884.08 |

|

| Total | – | -1.56 | -1.60 | 2,355.09 | 266.24 | 2,621.33 |

|

Figure 7. Distributional impact of the equalisation of petrol and diesel taxes by equivalent income deciles

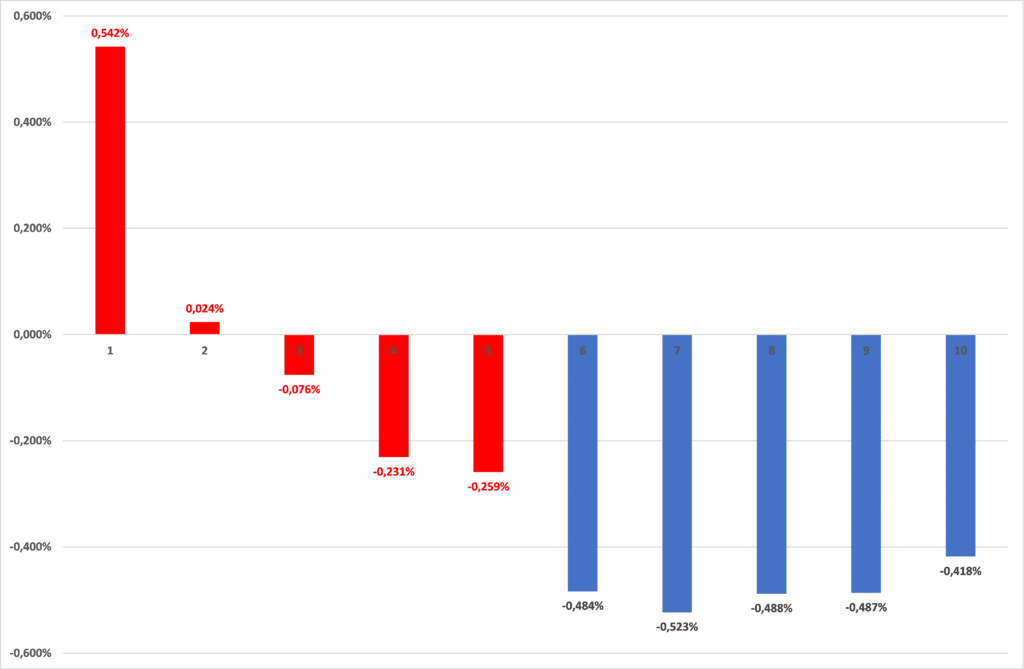

A joint analysis of the preceding proposals, together with the measures proposed for the electricity sector (elimination of the IVPEE and reduction of the IEE), is particularly interesting and provides a core result of the WB. Table 4 shows that such a comprehensive simulation would have a significant impact on the prices of energy products, allowing a significant reduction in CO2 emissions, and would generate additional revenue of close to 9 billion euros. The combination of these proposals would have a progressive impact (Figure 5), which would be enhanced if compensation were made through lump-sum transfers to the five lowest income deciles (so that, on average, these households would not be affected by the reform, as shown in Figure 8).

Figure 8. Impacts on prices, consumption/emissions and revenue of the elimination of the IVPPE, the reduction of the IEE and the increase in taxation of hydrocarbons

| Price (%) | Consumption and CO2 emissions (%) |

Additional revenues (€ mn ) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IVPEE | IEE | CO2 Tax (ETS) | FNSSE | VAT | Total | |||

| Residential electricity | -11.63 | 2.36 | -372.31 | -731.47 | – | -912.12 | -318.47 | -1,422.25 |

Non-residential |

-17.37 | 3.53 | -468.88 | -583.69 | – | -1,255.29 | – | -1,052.57 |

Non-residential |

-14.18 | 2.88 | -286.86 | -53.60 | – | -762.46 | – | -340.45 |

| Gasoline-95 | 15.47 | -3.91 | – | -116.63 | 692.87 | 311.42 | 155.37 | 1,043.03 |

| Residential diesel | 27.76 | -5.58 | – | 1,167.48 | 2,183.67 | 841.72 | 753.69 | 4,946.57 |

| Non-residential diesel | 29.19 | -5.87 | – | 713.21 | 1,300.58 | 501.32 | – | 2,515.11 |

| Residential natural gas | 21.81 | -5.28 | – | 42.58 | 503.48 | 276.64 | 129.76 | 952.45 |

| Non-residential natural gas non-EU-ETS | 48.55 | -11.75 | – | 218.05 | 755.03 | 414.85 | – | 1,387.94 |

| Non-residential natural gas EU-ETS | 22.25 | -5.39 | – | 311.72 | – | 583.91 | – | 895.63 |

Total |

– | -3.70 |

-1,128.04 | 967.66 | 5,435.63 | – | 720.34 | 8,925.47 |

In any case, the measures would also have a significant impact on certain economic activities, so it would be advisable to implement the reform gradually, to limit its impact on inflation and GDP, and to use part of the revenue to incentivise a transformation that is compatible with the ecological transition of the most affected sectors. In the case of natural gas, it would be advisable to use part of the revenue to encourage the development and implementation of less polluting technologies (biogas, green hydrogen, etc) to protect the competitiveness of the industrial sector.

Figure 9. Distributional impacts by equivalent income deciles of the elimination of the IVPPE, the reduction of the IEE and the increase in the taxation of hydrocarbons

Figure 10. Targeted compensation impacts of the suppression of IVPPE, reduction of the IEE and increase in the taxation of hydrocarbons, by equivalent income decile

A key tool to facilitate the green transition in transport is the IEDMT, as vehicle purchasing decisions ultimately determine the environmental impacts associated with their lifetime. Thus, purchase taxes, if appropriately designed and applied, will promote the purchase of low-emission vehicles, and are therefore key to achieving reductions in the environmental externalities of road transport. Vehicle purchase taxes, being more visible, are also more effective in influencing consumers’ purchasing decisions than annual road taxes (Gerlagh et al., 2018). In these circumstances, a first WB proposal would be to extend the number of tax brackets and increase tax rates in order to incentivise the purchase of low-emission vehicles. It would also be advisable to introduce a vehicle weight surcharge above a certain threshold to discourage the purchase of large vehicles, which are a source of significant negative externalities (Shaffer et al., 2021). Since the current IEDMT rates are applied on sales price, the most polluting low-priced vehicles might face comparatively low payments. This could be solved by modifying the current ad-valorem levy on the price by a unitary tax levied on the expected emissions of the vehicle (the Dutch approach). The simulation of these measures shows a regressive distributional impact, which could be offset by exclusively targeting existing fleet renewal at lower income groups.

The WB also recommends actions to introduce environmental variables into the IVTM, so that it contributes to an earlier replacement of highly polluting vehicles by clean alternatives. To this end, its design could be changed from levying the tax on the so-called fiscal power to the use of indicators of environmental damage, such as their environmental category (Euro), the official environmental classification labels of vehicles, or their level of CO2 emissions.

On the other hand, existing taxes on transport are currently ineffective in tackling congestion and local pollution, which are a significant part of the negative externalities associated with road transport, particularly in urban areas. It would therefore be advisable to introduce a vehicle tax that varies according to time of day and location, depending on the volume of traffic. Such a tax would reduce unnecessary journeys, generating significant benefits for users who really need access to congested areas. However, this charge could have regressive impacts, as it does not take into account the economic capacity of each driver, which could be mitigated by earmarking part of the revenue for public transport improvements (Fageda & Flores-Fillol, 2018). With respect to road infrastructure costs, although the environmental taxes considered above can contribute to their coverage, pay per use systems are more efficient and transparent approaches to this end. Therefore, it would be advisable to consider the introduction and extension of charges for the actual use of certain transport infrastructures.

Even though the above-mentioned measures could be implemented in the short term, the fall in revenue associated with road transport that has occurred in recent years reflects structural problems that will require deep regulatory and tax changes. Both technological advances and changes in consumer habits are reducing the revenue-raising capacity of transport taxation, but negative externalities and other uncovered costs remain as existing taxes are unable to adequately address them. Therefore, in the medium term the WB contemplates the introduction of a tax on actual vehicle use that addresses the important externalities of transport while maintaining high and stable tax revenues. This tax would be based on the use of vehicles but would discriminate according to the type of vehicle and place and time of use, allowing the costs associated with road transport to be incorporated into the decision-making process of agents (Gago et al., 2019). The tax on the use of vehicles should replace most existing taxes (on fuels and vehicle ownership) or those to be introduced in the near future (congestion and infrastructure use).[4] The various externalities would be taxed according to the distance travelled by type of vehicle (accidents, climate change) and the time and place of use (congestion and local pollution). In any case, the introduction of such a tax should be gradual and should pay particular attention to its distributional impacts. Given the complexity and magnitude of the reform, detailed pilot evaluations should be carried out in advance.

Increased circularity

The so-called circular economy is a model of sustainable socio-economic development that aims to reduce the linear flow of materials in production and consumption processes, by extending the useful life and relocating waste from the end of the supply chain to the beginning. In this context, many of the tax proposals in this area aim to minimise material use and waste by reinforcing re-use and recycling. Considering circularity as a general strategy to reduce material use and environmental degradation, other tax proposals are included in this section.

Inadequate waste management contributes to climate change and air pollution, and directly affects ecosystems and species (EEA, 2014), while the extraction and transport of aggregates causes landscape disturbance, effects on biodiversity and pollution of various kinds, as well as being a non-renewable resource. The inefficient and excessive use of nitrogen fertilisers can pollute water and soil and cause impacts on ecosystems and human health, while atmospheric pollution causes significant impacts on human health, as well as ecological alterations and biodiversity loss.

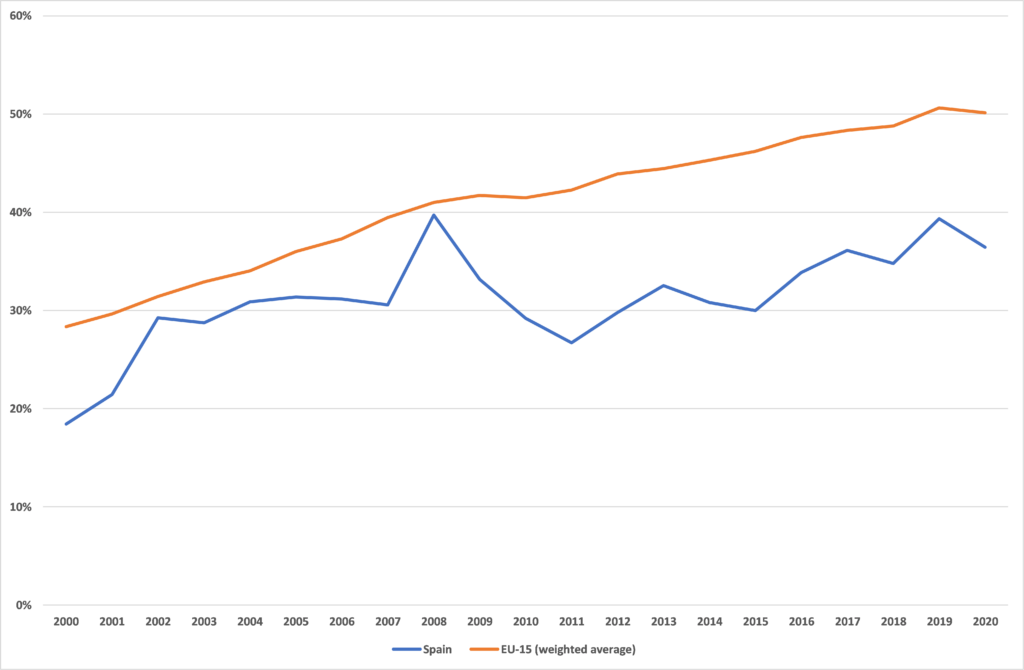

In Spain’s case, there are a series of commitments in the field of the circular economy that in many cases are far from being fulfilled and although municipal waste has been reduced in recent years its treatment has not improved significantly, so that the level of recycling is far from the European average since the beginning of the century (Figure 5), while the percentage of waste that ends up in landfills (48.2% in 2018) is well above the EU average (38.5%) (Eurostat, 2021b).

Currently, the existing taxes related to this section in Spain include waste charges, which are local in scope and generally used to tax waste collection and treatment services. These taxes are highly heterogeneous and they generally do not depend on the actual waste generation of each agent: therefore they do not provide incentives for reduction or selective collection (OFR, 2021). There are also a number of specific taxes at the regional level that tax the deposit and/or disposal of various types of waste, with a wide range of tax rates, as well as a tax on single-use plastic bags in Andalusia. In addition, the recent Law on Waste and Contaminated Soils (LRySC) introduces two taxes: a levy on the deposit of waste in landfills, incineration and co-incineration (IEDVIR), which will replace similar existing taxes at a regional level: and a tax on non-reusable plastic packaging (IEPNR) that will be levied on single-use plastic packaging according to the amount of plastic it contains. Moreover, several regions have their own taxes on emissions of different atmospheric pollutants (NOx, sulphur oxides, CO2, VOCs, NH3 and particulate matter).

Figure 11. Percentage of municipal waste recycled in Spain and EU-15, 2000-20

Source: CPELBRT (2022) from Eurostat (2021b).

In this context, given the limited effectiveness of the regulatory approaches applied so far to waste and the use of materials, it is advisable to reformulate the strategies and instruments to achieve Spain’s environmental objectives. Within policies for making progress in the circular economy, taxation is a key instrument due to its capacity to provide incentives for agents to reduce waste and the use of materials. Thus, the specific tax proposals to favour the circular economy consist of the intensification and extension of the LRySC taxes, the reformulation of municipal waste taxation to link it to pay-as-you-throw systems, the creation of a tax on aggregate extraction, the introduction of a tax on nitrogen fertilisers, and the extension and harmonisation of taxation on certain emissions from large industrial and livestock facilities.

Regarding the IEDVIR, the WB recommends establishing an increasing path of its real tax rates in order to intensify the effects of the tax and ensure its gradual application so as to achieve an effective change in behaviour and the progressive abandonment of landfilling and incineration. In relation to the IEPNR, it would be appropriate to consider its extension to other packaging categories, in order to encourage their reduction and the use of more environmentally friendly packaging.

In relation to municipal waste, since recycling and reduction figures are well below EU requirements (Figure 2), the WB recommends a substitution of the current system of municipal taxation to charges related to actual waste generation. This would involve measuring the waste produced by each household or firm and determining the tax payment according to the amount generated and the type of waste, thus creating incentives for waste reduction and separate waste collection. A simple simulation of the introduction of an increase in existing municipal waste charges by introducing a surcharge on mixed waste according to its weight shows that an additional charge of €0.05/kg could achieve a significant reduction in the generation of mixed waste, although it would have a regressive distributional impact. In any case, these negative distributional impacts should be compared with those brought about by other existing alternatives to meet the Spanish waste reduction and separate waste collection targets, such as a generalised linear increase in existing waste charges. Regarding aggregates, given the large gap in Spain between the targets for non-hazardous construction waste for reuse and the reality (Figure 2), it is recommended that a tax on aggregates extraction be introduced to encourage a reduction in consumption and an increase in the use of recycled materials in construction.

Nitrate pollution from agriculture, caused by an excessive use of fertilisers, is a very important environmental externality in Spain. As it is diffuse pollution, it is difficult to identify the cause of the problem, so the introduction of a mineral nitrogen tax could lead to a second-best solution (Jayet & Petsakos, 2013). Therefore, the WB proposes the implementation of a tax on the nitrogen contained in certain fertilisers so that part of the environmental costs are incorporated in their price, discouraging the abusive use of the most harmful fertilisers and favouring less polluting options. Moreover, given that these products enjoy a reduced VAT rate in Spain, it would also be desirable to raise it (in line with other proposals of the WB regarding indirect taxation). In any case, a gradual introduction of this tax would be advisable in order to avoid significant impacts on the agricultural sector, as well as the application of compensatory mechanisms and an adequate transmission of the correction of environmental costs to consumers.

Finally, there are certain atmospheric emissions that have significant impacts on climate change, human health, ecosystems and infrastructures. The emitters of these pollutants include large industrial facilities and livestock farming (especially intensive livestock farming), and it would therefore be advisable to introduce a tax on NOx, CH4, CO, NH3, COVDM and N2O emissions caused by large industrial complexes, as well as CH4, NH3 and N2O emissions from intensive livestock farming.[5] Using data from MITECO (2021b), applying a tax rate equivalent to one fifth of the environmental damage of each pollutant as calculated by CE Delft (2018) and assuming that agents do not react to taxes, Figure 12 shows that such a measure would generate significant revenues (note that environmental and price effects are not calculated due to the lack of data). Yet a gradual introduction of this tax and a partial revenue refund would be advisable to facilitate the adoption of cleaner technologies. Tax rebates based on the use of best available technology or best operating techniques would also be desirable.

Figure 12. Emissions, tax rate and revenue from emission taxation of large industrial sites and intensive livestock farming

| Pollutant | Emissions (tonnes) | Tax rate (€/kg) | Revenues (€ mn) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NH3 | 2,783.50 66,449.4 | 3.5 | 9.74 232.57 |

| COVDM | 52,925.07 | 0.23 | 12.17 |

| CH4 | 165,640.36 232,380.2 | 0.348 | 57.64 80.87 |

| CO | 261,026.34 | 0.011 | 2.75 |

| N2O | 2,220.21 987 | 3 | 6.66 2.96 |

| NOx | 178,012.09 | 2.96 | 526.91 |

| Total | 810,740.56 | – | 615.88 316.41 |

Source: CPELBRT (2022).

Incorporation of environmental costs associated with water use

Problems related to the availability of quality water are particularly serious and affect essential socio-economic sectors in Spain, generating significant environmental impacts. Indeed, Spain is one of the most arid countries in the EU, with a high degree of water stress, with droughts and periods of scarcity, problems that are being aggravated by climate change. However, per capita water consumption in Spain is among the highest in the EU, mainly due to its use in the agricultural sector.

Water governance in Spain is particularly complex, as it involves different administrative levels that sometimes act in an uncoordinated manner, resulting in a high degree of heterogeneity between territories, which, although desirable due to the high regional disparities, can sometimes lead to unjustified and inefficient differences in regulations and prices. Water management in the EU is based on the application of the EU Water Framework Directive, which establishes the principle of recovery of the costs of water-related services, including environmental costs and those related to water resources, as a key element in the definition of water policy. However, the degree of recovery of the cost of water services is below 70% in Spain. In this context, the European Commission (2019) recommended Spain should strive for cost recovery based on the ‘polluter pays’ principle to ensure sustainable water management.

The basis of the water tax regime in Spain has not been modified since the 1985 Water Law. At present, state water taxes include taxes on the use of the public domain (tax on the occupation, use and exploitation of public water assets and tax on the occupation of the maritime-terrestrial public domain), taxes to recover the cost of water infrastructures (regulation tax and water use tariff) and the discharge control levy. In addition, most Spanish regions have introduced their own taxes on taxable events linked to the different stages of the water cycle, mainly in the sanitation and discharge treatment phases. In many cases, local authorities apply charges and tariffs for the supply and treatment of wastewater.

The use of environmental water taxation can be justified to ensure compliance with the ‘polluter pays’ principle by internalising environmental damage caused by the discharge of pollutants into watercourses, but also to promote the efficient use of a scarce resource, as well as to contribute to covering the infrastructural and operational costs associated with water supply. Therefore, the specific proposals for the reform of water taxation consist of the introduction of coordination and cooperation measures to improve the design and effectiveness of regional taxes on environmental damages to water, the reform of taxes associated with the coverage of water infrastructure costs and the creation of a tax on the extraction of water resources.

First, considering that there is a high level of use and heterogeneity of the regional water taxes on environmental damage, several measures to improve their design and effectiveness are necessary. With regard to taxes on sanitation, it would be advisable to maintain the existing regional taxes but differences between municipalities within each region should be avoided. Moreover, it should be considered that some regional taxes have a wider scope of application than wastewater production. A national tax could also be created with a compulsory part on wastewater production and an optional part on water infrastructures. With regard to taxes related to environmental damage caused by certain uses of dammed water, it would be advisable to intensify their environmental characteristics. For their part, taxes on discharges into coastal waters could be maintained at the regional level, but their environmental nature could also be strengthened.

Secondly, the state taxes associated with covering the costs of hydraulic infrastructures are poorly regulated, which leads to a high level of litigation, so they should be reviewed in such a way that technical improvements are made to both the qualitative and quantitative elements of the current taxes, regulating the amount to be collected and its distribution among taxpayers.

Finally, it is recommended to create a state tax on water abstraction with a simple configuration that encourages the appropriate use of a scarce resource, while at the same time helping to generate resources to carry out measures that do not have a cost-recovery instrument. The tax would have as its taxable base the volume of water abstracted and its quota would be proportional to this, with the possibility of applying a use factor and a territorial factor, depending on the difficulties of abstraction.

Discussion and implications

Many things have changed since the constitution of the Spanish expert group for the WB on tax reform in early 2021. The IPCC (2022) completed its 6th Assessment Report, which provides a worrying picture of the sizeable impacts of climate change and the shortcomings of mitigation strategies across the world. A Summer of record temperatures in the Northern hemisphere, still with GHG concentrations well below those of 1.5ºC levels, also pointed to the urgency of taking action. Particularly, after growing price tensions from mid-2021, a severe energy crisis fully exploded following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

In this context, are the energy and environmental proposals of the WB still valid? Many Spanish policymakers, industry representatives and commentators thought that the environmental chapter of the WB had been born dead and was not applicable in the real world. Nine months after its presentation, I believe that many of its suggestions are still fully valid to fight the energy and climate crises and to effectively protect those badly affected by the energy price spiral.

Indeed, in a context in which major energy tensions should not endanger the environmental agenda but also offer new reasons to accelerate the ecological transition, energy-environmental taxation is reinforced in its role to incentivise more energy efficiency and a larger deployment of non-fossil alternatives. Additionally, the current crisis also shows the urgent need for well-designed and permanent measures to mitigate the distributional impacts generated by increasing energy prices. In sum, two major contributions of the WB as summarised in this paper.

The simultaneous reduction of fiscal barriers to electrification (renewable), without ignoring the necessary internalisation of the environmental costs of electricity generation, and the intensification of the taxation of fossil consumption and technologies (particularly relevant in the field of transport) are the focus of the WB’s proposals in the energy and climate domains. Contrary to the opinion of some Spanish industrial lobbies, the aim of the WB is not to penalise but to promote a gradual change in equipment and its use by households and companies to achieve an efficient transition to decarbonisation, in which taxation must form part of a broad and coordinated policy package. Although there is a pervasive Spanish anomaly regarding the use of environmental taxes, the current need to curb the huge fossil fuel dependence through behavioural and technological changes recommends an automatic replacement of price falls by higher environmental taxes.

The WB and this working paper have also stressed the need for compensatory packages associated to more stringent environmental and climate policies. The WB suggests that a solid and lasting compensatory system for the ecological transition should be made up of transfers that are not linked to lower fossil fuel prices and are not generalised, supporting only households below a certain level of income. It is also convenient to reinforce these compensations with non-generalised programmes that accelerate the change of equipment, again facilitating the adoption of clean technologies for those groups with limited access to capital.

Unfortunately, as in most EU countries, the Spanish government has introduced solutions far removed from the WB’s proposals in the energy and environmental domain. Generalised subsidies on polluting goods are indeed against the corrective needs of environmental and climate policies and are also imperfect compensatory devices. In Labandeira et al. (2022) we provide empirical evidence on the several environmental, energy, public expenditure and distributional shortcomings of such offsetting policies, making them clearly inferior to those suggested by the WB.

References

ACEA (2021), ACEA Tax Guide.

CE Delft (2018), Environmental Prices Handbook. EU-28.

CNMC (2020), Informe sobre la Liquidación Definitiva de 2019 del Sector Eléctrico, Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia.

CPELBRT (2022), Libro Blanco sobre la Reforma Tributaria, Comité de Personas Expertas para Elaborar el Libro Blanco sobre la Reforma Tributaria.

CORES (2021), Estadísticas.

Eckstein, D., V. Künzel, L. Schäfer & M. Winges (2020), Global Climate Risk Index, Briefing Report, Germanwatch.

EEA (2014), Waste: A Problem or a Resource?, European Environmental Agency.

European Commission (2019), Segundos Planes Hidrológicos de Cuenca: España, SWD, 26/II/2019.

European Commission (2021a), ‘Proposal for a Council directive restructuring the Union framework for the taxation of energy products and electricity’ (recast), COM (2021) 563 final.

European Commission (2021b), Taxation Trends in the European Union.

Eurostat (2021a), Energy Database.

Eurostat (2021b), Waste Database.

Eurostat (2021c), Road Transport Equipment. Stock of Vehicle.

Fageda, X., & R. Flores-Fillol (2018), ‘Atascos y contaminación en grandes ciudades: análisis y soluciones’, Fedea Policy Papers, 2018/04.

Fullerton, D., A. Leicester & S. Smith (2010), ‘Environmental taxes’, in S. Adam et al. (Eds.), Dimensions of Tax Design, Oxford University Press.

Gago, A., X. Labandeira, J.M. Labeaga & X. López-Otero (2021a), ‘Transport taxes and decarbonization in Spain: distributional impacts and compensation’, Hacienda Pública Española/Review of Public Economics, nr 238, p. 101-136.

Gago, A., X. Labandeira & X. López-Otero (2014), ‘A panorama on energy taxes and green tax reforms’, Hacienda Pública Española. Review of Public Economics, nr 208, p. 145-190.

Gago, A., X. Labandeira & X. López-Otero (2019), ‘Taxing vehicle use to overcome the problems of conventional transport taxes’, in M. Villar-Ezcurra et al. (Eds.), Environmental Fiscal Challenges of Cities and Transport, Edward Elgar Publishers, Cheltenham.

Gago, A., X. Labandeira & X. López-Otero (2021b), ‘Imposición ambiental en España. Un resumen de la literatura académica’, WP 01/2021, Economics for Energy.

Gerlagh, R., Inge van den Bijgaart, H. Nijland & T. Michielsen (2018), ‘Fiscal policy and CO2 emissions of new passenger cars in the EU’, Environmental and Resource Economics, nr 69, p. 103-134.

Government of Canada (2020), Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change, Third annual synthesis report on the status of implementation, https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2020/eccc/En1-77-2019-eng.pdf.

Harding, M. (2014), ‘The diesel differential: differences in the tax treatment of gasoline and diesel for road use’, OECD Taxation Working Papers, nr 31.

INE (2021a), Encuesta de Condiciones de Vida, Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

INE (2021b), Encuesta de Presupuestos Familiares, Instituto Nacional de Estadística.

IEF (2021), Opiniones y Actitudes Fiscales de los Españoles en 2020, Documento de Trabajo, nr 5/2021.

IPCC (2022), Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change, Working group III contribution to the sixth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Jayet, P.-A., & A. Petsakos (2013), ‘Evaluating the efficiency of a uniform N-input tax under different policy scenarios at different scales’, Environmental Modeling & Assesment, nr 18, p. 57-72.

Labandeira, X., J.M. Labeaga & X. López-Otero (2016), ‘Un metaanálisis sobre la elasticidad precio de la demanda de energía en España y la Unión Europea’, Papeles de Energía, nr 2, p. 65-93.

Labandeira, X., J.M. Labeaga & X. López-Otero (2022), ‘Canvi climàtic. Fiscalitat i compensacions distributives’, Revista Econòmica de Catalunya, nr 85, p. 63-70.

MITECO (2021a), Precios de Carburantes y Combustibles. Comparación 2020-2019.

MITECO (2021b), Registro Estatal de Emisiones y Fuentes Contaminantes.

OECD (2015), Aligning Policies for a Low-carbon Economy.

OECD (2021), Environmentally Related Tax Revenue by Country.

OFR (2021), Las Tasas de Residuos en España 2021, Fundació ENT.

Pizer, W., & S. Sexton (2019), ‘The distributional impacts of energy taxes’, Review of Environmental Economics and Policy, nr 13, p. 104-123.

Rivers, N., & B. Schaufele (2015), ‘Salience of carbon taxes in the gasoline market’, Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, nr 74, p. 23-36.

Shaffer, B., M. Auffhammer & C. Samaras (2021), ‘Make electric vehicles lighter to maximize climate and safety benefits’, Nature, nr 528, p. 264-266.

Van Essen, H., L. van Wijngaarden, A. Schroten, S. de Bruyn, D. Sutter, C. Bieler, S. Maffii, M. Brambilla, D. Fiorello, F. Fermi, R. Parolin & K. El Beyrouty (2019), Handbook on the External Costs of Transport, Version 2019-1.1, Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg.

[1] The government has suspended the application of the IVPEE on several occasions since 2018, while the Supreme Court has annulled part of the regulation of the tax for the use of inland waters for electricity production. Since 2021 the government has established temporary measures to reduce the level of the above-mentioned taxes as part of the packages to fight the energy crisis.

[2] Although natural gas is only marginally used in transport, it is included in this section due to its presence in the new ETD.

[3] The simulated (€50/t) carbon tax intends to capture the effects of the Fit for 55 new emissions trading system for transport and buildings. The FNSSE, currently under parliamentary procedure, aims to transfer the fixed costs of the specific remuneration regime for renewable, cogeneration and waste facilities, associated with previous systems for the promotion of renewables, to all operators in the energy sectors.

[4] Only the IEDMT should be maintained to ensure that purchasing decisions of vehicles are compatible with the extensive efforts to reduce negative externalities.

[5] As mentioned above, several regions apply their own taxes on some of these emissions, so the tax could set minimum tax rates giving regions the regulatory power to increase them.

Image: Urban orb. Photo: Joshua Rawson-Harris (@joshrh19).