Summary

The steep upsurge in the number of drug-related homicides in Mexico has been matched by an even greater increase in the news coverage of violence and organised crime. However, both journalists and scholars have overlooked how organised crime makes use of the media and vice versa. By drawing on previous research on the relationship between the media, terrorism and public opinion this Working Paper looks into the rise of mass-mediated organised crime in Mexico.

Based on a quantitative analysis of the news coverage of violence and organised crime in three major newspapers as well as a qualitative study of selected events, the paper offers an insight to understand the political ramifications of the news coverage of violence. Even when drug trafficking organisations are not terrorists who seek the publicity of the press to advance a political cause, this paper shows that they have important goals related to the media, the impact of news on public opinion and the consequent influence over policy making.

Introduction

When José Contreras Subías, one of the most important criminal bosses at the time, escaped from prison in 1985, there was commotion across the country. People heard and read different versions about how he had managed to escape. One official, for instance, claimed that a group of gunmen outnumbering the security officers at Tijuana’s municipal gaol came to set him free. However, just after fleeing north to hide in a ranch in Oklahoma, Contreras Subías sent a personal employee to Zeta, a local newspaper in Tijuana. She was ordered to tell the real story behind the prison break.

According to her version, José Contreras had long enjoyed the privilege of being released on a regular basis. The Capo was allowed to get out of prison on Fridays and then expected to return every Sunday. On 25 October 1985 he simply decided not to return. The woman told the newspaper’s editor, Jesús Blancornelas: ‘Don José sent me. He asked me to speak to you so you would publish the truth instead of the nonsense that is being said now’ (Blancornelas, 2002).

Just before sunset gave way to cooler air in the Port of Veracruz, a group of at least six vehicles full of gunmen wearing masks and fake military uniforms hit the Ruiz Cortínez Boulevard. They escorted two flatbed trucks along the beach up to the grade separation near the hotel area, just in front of the monument to the Papantla Flyers erected on a green traffic island.

Some of the armed men descended to clear the road by pointing their weapons at frightened motorists who rapidly took alternative routes. The rest of the men abandoned the trucks across the boulevard and placed two white banners with an inscription in black. In a matter of seconds, they fled from the scene.

Veracruz is a symbol of joy, intemperance and pleasure. The song La Bamba, made famous by Ritchie Valens in the US, is rooted in the region’s traditional music, the son. On the evening of 20 September 2011, however, the mood of the port would be shattered. After expanding across the country, the drug wars finally reached Veracruz. The abandoned flatbed trucks were loaded with 35 dead bodies with visible signs of torture. The message on the banners read: ‘This is going to happen to every shitty Zeta that remains in Veracruz. The territory has a new owner: New Generation. Here lies “El Ferras” and his royal entourage’.

Unexpected chaos came on 9 March 2012 to the usually serene lives of people in Guadalajara, Mexico’s largest and wealthiest urban area in the western-pacific region. Many roads were blocked and chaos reigned. Gunmen hijacked buses, cars and tractor-trailers throughout the city. They set them alight and placed them across the streets to obstruct main intersections.

Minutes before, the military had captured Erick Valencia, the leader of the Jalisco New Generation cartel; the drug trafficking organisation was resolved to rescue him. An intense shoot-out took place but failed to prevent the army from arresting the criminal suspect, known in the underworld as ‘The 85’.

The drug traffickers responded with blockades all over the city to block the military’s route and free their boss. However, the Capo was already flying in an armoured helicopter to Mexico City, where the Federal Prosecution Office would initiate his trial and conduct further investigations about the cartel’s operations. There were several shoot-outs that put the city in a state of terror. A gunman was shot dead by the army and another was seriously injured. The driver of one of the hijacked buses was burnt to death and a seven-year-old girl was killed in the crossfire.

The following Monday, at least five banners were found hanging from pedestrian bridges and traffic signs throughout the city. The message was meant for the citizens of Guadalajara: ‘We apologise for the violent events of last Friday. It was only a reaction for messing with a comrade from the Cartel New Generation of Jalisco (CJNG), who was only devoted to working in our business and keeping the peace and tranquillity of the state of Jalisco… As long as the police forces stay away, the CJNG will not retaliate’.

Episodes such as these are not rare in Mexico, especially after President Calderón launched a frontal assault on drug-trafficking organisations (DTOs) five years ago. However, they have a common feature that has been systematically neglected by scholars and journalists when analysing organised crime: all these events show that drug cartels have an interest in the media, that they are worried about the way the press covers theirs news and that they are interested in conveying a message to the general public.

Also, as shown by extensive research on the media, terrorism and public opinion, violence provides ‘what contemporary news media crave most: sensation, drama, shock and tragedy suited to be packaged as gripping human-interest narratives’ (Nacos & Bloch-Elcon, 2011, p. 692). As expected, the recent and steep upsurge in the number of drug-related homicides in Mexico has been matched by an even greater increase in the news coverage of violence and organised crime.

However, little attention has been paid by scholars and journalists to addressing the political relevance of news on criminal syndicates and violence, even when it is increasingly evident that media coverage has played a central role in Mexico’s war on drugs. In March 2011 many of the most important media outlets in Mexico gave the misleading idea that they were conscious of this relationship and also willing to take action. They signed an agreement to cover violence in compliance with set standards and limits. Since then, the agreement has been openly disregarded.

By drawing on previous research on the relationship between news coverage and terrorism, this paper looks into the way the media and criminal syndicates have built up a relationship that is close to complicity. Aware of the differences between terrorism and criminal organisations, it is suggested that even while drug-trafficking groups are not terrorists who seek the publicity of the press to advance a political cause, they have important goals related to the media, the impact of news on public opinion and the consequent influence over policy making. The argument proceeds as follows.

The first section offers an explanation as to why there has been such an underestimation of the cartels’ interest in the media, as well as the ways in which news organisations cover organised crime. This section tries to set the building blocks of a conceptual framework capable of providing an insight into mass-mediated organised crime, borrowing the concept from analogous studies on the media and terrorism (Nacos, 1997). It is argued that, as a relatively recent but not new phenomenon, it shapes the discussion about security policy and the fight against drug-trafficking organisations.

A second section is devoted to understanding the relevance that the media has conceded to violence and organised crime in Mexico. By analysing the number of news articles published in national papers during the past five years, it is shown that violence has been overwhelmingly covered, attracting much more attention than equally or even more pressing social issues such as poverty, health care and unemployment.

A third section presents a qualitative analysis of the complete coverage given to three selected events by the three major elite newspapers across the ideological spectrum in Mexico: Reforma (right-wing), El Universal (centre-right), and La Jornada (left-wing). All of them involved military operations that led to the capture of a criminal leader, with the cartels reacting violently to the enforcement actions.

Finally, a concluding section highlights the paper’s most important findings and discusses their implications on both the media and policy-makers. It stresses the relevance of future research on this relationship as a necessary part of understanding the overall incentives and behaviour of criminal organisations, as well as the way they are confronted by the State. Equally important, it argues, is the need for a serious debate about the media coverage of violence. Even if there is no consensus ‘on the diagnosis of a malaise or even whether a malaise exists at all… mass media reporting is too important to be left to reporters’ alone (Weimann & Winn, 1994).

As terrorism has already done elsewhere, organised crime makes use of the media and the media reciprocate with organised crime. To what extent have criminal syndicates in Mexico succeeded in exploiting the mass media for their communication goals? What have been the political consequences? These are the questions that this paper seeks to answer. As Nacos has said about terrorism, while organised crime and news organisations might not be loving bedfellows, ‘they are like partners in a marriage of convenience’ (Nacos, 2007, p. 107).

While there is no evidence regarding the existence of a deliberate strategy of drug-trafficking organisations to make it to the news, the point of this paper is that the outcome has been beneficial to them. Even if they did not intend that to happen, media outlets have given a great deal of coverage to violence and security policies. In doing so, they have also changed how violence and security policies are framed, thus influencing public opinion.

Organised Crime and the Media: A Framework for Analysis

The way in which violent groups have been defined is at the core of explaining why both the media and academia have not paid attention to how the media and criminal syndicates interact. For instance, the social sciences have almost unanimously stated as an essential distinction between terrorists and criminal syndicates that the former are driven by ideology, religion and politics, while the latter are purely profit motivated (Sanderson, 2004). Since criminals are understood to be illegal entrepreneurs only, analysts have overlooked their social or political attitudes and strategies.

However, to fully understand organised crime it is necessary to be aware that drug organisations, while being mainly profit driven, operate in a broader political and social system which they want to influence. In this respect, criminal syndicates share with terrorists more than the use of extreme violence to commit felonies and challenge the State and the rule of law. Criminal groups are also alike in that they need to operate secretly most of the time, but they always try to build friendly territories in which they can act publicly and confidently (Sanderson, 2004).

On a regular basis, criminal organisations as well as other non-state violent groups need to fulfil a series of tasks which are easier to accomplish with the cooperation of civil society. The most important resource of violent non-state groups is labour and human capital (Gambetta, 1996; Glenny, 2011). Recruiting becomes simpler when attitudes in a community, or at least in part of it, are more accepting towards violent groups.

In fact, as social scientists have shown recently, violent non-state organisations can enjoy the support and approval of citizens in nations experiencing high levels of conflict and where the State has failed to guarantee public safety (Walter, 2009; Weinstein, 2007; Berman, 2009; Díaz-Cayeros et al., 2011). This is the case of countries such as Afghanistan and Pakistan in Asia, the Republic of Congo and Zimbabwe in Africa, and Colombia and Mexico in Latin America.

Just like the legal private-sector organisations in industry and commerce that approach politicians in search of trade benefits, fiscal preferences and regulatory privileges, criminal syndicates also try to use their own resources to influence policy decisions. They want to build a friendly environment for their business and the media can help them in pursuing these objectives.

Drawing from the work of Nacos (2007), who developed a typology of the media-centred goals of terrorists, this paper takes the categories that might also suit the case of drug trafficking organisations in Mexico. Nacos proposed that whenever terrorists strike or threaten to commit violence, they strive for: (1) attention/awareness; (2) recognition; (3) respect and sympathy; and (4) quasi-legitimacy.

Of the four objectives pursued by terrorists, two –numbers (3) and (4)– are easily compatible with Mexican criminal organisations, while another one can fit the case with a slight conceptual change (1). The fourth, the goal of recognition, which states that terrorists ‘want their political causes to be publicised and their motives discussed’ (Nacos, 2007, p. 21), does not apply to criminal organisations, which certainly do not have a political motivation but are profit driven.

Respect and sympathy are goals that terrorists attain by acting (or suggesting they act) on behalf of a certain community they claim to represent. In the case of the drug cartels, although they do not claim to represent any community, they try to gain society’s sympathy as indicated by the so called narco-messages, narcomantas, where they ask the government to stop the war against them.

Their argument is that they are not in the business of harming the population (meaning crimes such as kidnapping, extortion, racketeering or the murder of civilian’s assassination), but in that of trafficking. They also claim to protect society and fight the organisations that do commit such violent crimes.

Cartels aspire to make a case in the media to convince people that their actions are just part of the business of trafficking, and that they do not increase insecurity. The banners deployed in March 2012 in Guadalajara, apologising for the inconvenience caused by the criminal blockages throughout the city, are also a vivid example of this attempt to gain the people’s approval.

Complementarily, criminal syndicates also have the goal of building violent reputations to dissuade people from cooperating with the government (Díaz-Cayeros et al., 2011) or simply deterring competition from other violent entrepreneurs. Gaining ‘respect’ in the underworld is in itself a useful asset (Ríos, 2011).

The second media-centred goal of drug-trafficking organisations, continuing the analogy of Nacos’s work, is to achieve a quasi-legitimate status. Probably the best example of an attempt of this nature occurred on 10 November 2010 when a criminal organisation known as La Familia Michoacana offered a truce to President Calderón if he and the military took over the control of the state of Michoacán, guaranteeing the safety of all the population.

The message was e-mailed to major newspapers in Michoacán, written in banners that hung from many footbridges and traffic signs throughout the state, while the head of the organisation gave a telephone interview to a popular programme on a local radio company. Even while the Mexican government denounced the press release, as Nacos (2007) argues, ‘wittingly or not, the news media bestow a certain status on terrorists leaders simply by interviewing them’ (Nacos, 2007, p. 21).

Drug lords have also been quite successful in turning themselves into role models for people who have the desire to make their way up in Mexico. In a very unequal society where opportunities are most of the time limited to those already in the upper crust of society, drug trafficking is a serious alternative for entrepreneurs (Ríos, 2010).

In building their image as role models, drug lords do not rely exclusively on the news media, but lean more heavily on the entertainment industry: a new musical genre, the narcocorrido, has emerged from the drug trafficking industry, making illegal criminal activities more attractive. Films have been made where murder, torture, racketeering, extortion and drug smuggling are trivialised while serious criticism is only levelled at government corruption.

The third objective, drawing attention and raising awareness, does not seem to match the case of criminal organisations, which most of the time prefer to remain unnoticed by State law enforcers. ‘Terrorists often seek out media coverage, whereas organised criminals avoid it… Criminal syndicates generally cultivate and maintain secret networks of illegal transportation, bribed or threatened customs officials, politicians, judges, police, and intelligence officials’ (Sanderson, 2004).

However, competition among the cartels is an incentive to grab the attention of the government in a strategic way, by promoting violence and conflict in the opponents’ territories. In this respect, it is not unusual to find criminal organisations allegedly claiming the authorship of a crime. This usually means that an enemy cartel has committed the crime but aims to divert the attention of the police to its competitors in order to displace them. The strategy is colloquially known as calentar la plaza and may be understood to mean ‘heating up the territory’. Drug organisations try to influence policy makers by turning the attention turn towards rival groups.

Drug-trafficking organisations aim to affect public opinion in ways that put pressure on governments. They are aware that even in imperfect democracies there are linkages between the media, public opinion and public policy. This argument might arouse scepticism in some readers who still think about drug traffickers as uneducated ranchers with big boots and cowboy hats, while there is plenty of proof that they are much more sophisticated entrepreneurs.

Drug-trafficking organisations have taken their money laundering to the banks of Wall Street (Langton, 2012). They have nominated candidates to run for public office and financed political campaigns for every political party in Mexico, according to government intelligence reports. They have even penetrated governments and markets in Africa and the Middle East, as recounted by international news organisations.

But criminal syndicates are not the only ones interested in making the news. Newsrooms are also fascinated by the opportunity of running bloody stories, which might attract a bigger audience. They know that violence has long been a strange but alluring spectacle to human beings. As Bok (1998) convincingly argued in Mayhem, people have long looked for violence as a means for entertainment. Ever since the Roman games in the arena to the contemporary production of films, video games or TV series, societies have consumed violent contents.

News corporations have not been unaware of this market reality, which has affected not only the kind of news they deliver but also the way in which they do it (Bok, 1998; Cottle, 2006; Nacos, 2000, 2007, 2011; Weimann & Winn, 1994). ‘Media organizations are rewarded as well in that they energize their competition for audience size and circulation—and thus for the all-important advertising dollar… In the coverage of terrorism, commercial imperatives seem to triumph over journalism ethics’ (Nacos, 2011, p. 691).

The Supremacy of Violence: Press Coverage in Mexico 2007-11

During the past five years, the media in Mexico have focused on covering public security news and stories. Among the 10 events with the highest media impact in the period, five are related to the death or assassination of public officials and the violence of the drug cartels. Three are the last occasions in which the President has addressed the nation in his annual state-of-the-union report or Informe as it is called, while the two remaining have to do with the Federal Cabinet, on the one hand, and the electoral alliance between the right and the left for the 2010 elections, on the other (see Table 1).

Security has captured the attention of both the national and international media all the way from newspapers and magazines to radio, television and the web. The coverage of violence partly depicts the relevance of public safety and the challenges it faces in Mexico. However, the media has reported violence in a disproportionate manner, giving the impression that the country is amongst the world’s most violent.

Table 1. The 10 events with the greatest press coverage, January 2007-March 2012

| Date | Event | Estimated Value in pesos | Number of news articles or opinion pieces |

| 2-Sep-10 | Fourth State-of-the-Union | 59,015.24 | 241 |

| 2-Sep-09 | Third State-of-the-Union | 54,930.66 | 327 |

| 11-Nov-11 | Death of Minister of the Interior, Francisco Blake | 49,601.61 | 158 |

| 6-Nov-08 | Death of Minister of the Interior, Juan Camilo Mouriño | 44,972.37 | 776 |

| 14-Jul-10 | Cabinet | 41,118.73 | 162 |

| 5-Mar-10 | Electoral alliance between PRD and PAN | 40,717.51 | 182 |

| 5-Nov-08 | Death of Minister of the Interior, Juan Camilo Mouriño | 40,246.17 | 586 |

| 2-Sep-10 | Drug cartels | 39,852.50 | 201 |

| 29-Jun-10 | Assassination of Rodolfo Torre (PRI-Tamaulipas) | 39,393.37 | 435 |

| 2-Sep-11 | Fifth State-of-the-Union | 38,888.11 | 216 |

Source: Infosis21, Executive Office of the Presidency, Mexico.

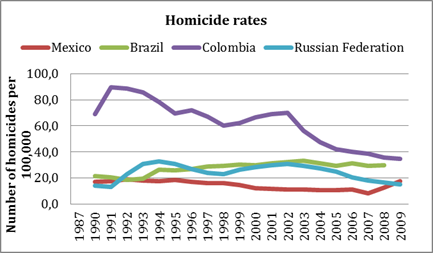

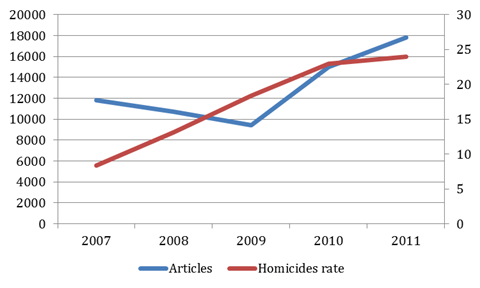

However, reality is not exactly that terrible. In Mexico there are half the violent killings that occur annually in Brazil (per 100,000 inhabitants) and a third of those in Colombia, a country far better known for its history of drug trafficking but which has recently been praised as a successful example in the fight against insecurity and organised crime. Certainly, Colombia’s homicide rate has dropped substantially and steadily over the past decade, but it is still much higher than Mexico’s (see Graph 1).

Graph 1. Homicide rates, 1987-2009

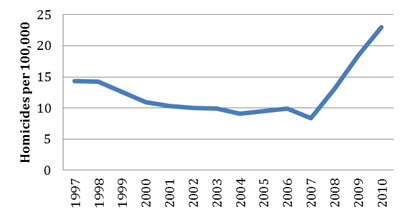

Violence in recent years has increased rapidly since 2007, when the homicide rate reached its lowest-ever level. However, the media has hardly acknowledged the fact that current murder rates are comparable to those of the 1990s. The media rarely provide historical context and usually offer short comparisons to achieve more attention-grabbing headlines such as ‘Record violence level’ (El universal, 1/VIII/2009, and La Jornada, 5/III/2012). While drug-related violence accounted for over 13,000 deaths in 2010, heart disease caused more than 105,000 deaths, diabetes almost 83,000, cancer 70,000 and accidents over 38,000.

Graph 2. Homicide rates in Mexico, 1997-2010

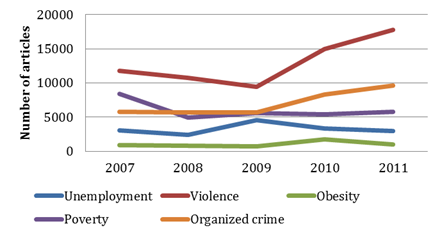

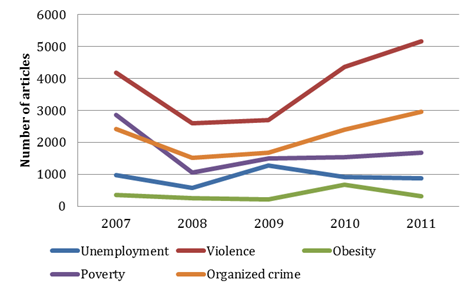

None of these issues by themselves reached made big news. There has been no public and sustained mass-mediated debate about the state’s capacity to provide health services. The federal government’s policy to reduce infant diabetes was a mediated issue for barely two weeks following the approval of new and still insufficient regulation. Table 2 shows the number of news articles each year in the three major newspapers that contain any of the following words, which are related to pressing social issues: unemployment, violence, obesity, poverty and organised crime.

Table 2. Number of articles in El Universal, La Jornada and Reforma, 2007-11

| Year | Unemployment | Violence | Obesity | Poverty | Organised crime |

| 2007 | 3,043 | 11,809 | 896 | 8,425 | 5,745 |

| 2008 | 2,446 | 10,727 | 807 | 4,937 | 5,671 |

| 2009 | 4,548 | 9,463 | 696 | 5,615 | 5,687 |

| 2010 | 3,350 | 15,002 | 1,743 | 5,443 | 8,335 |

| 2011 | 2,947 | 17,829 | 1,018 | 5,788 | 9,642 |

Source: Especialistas en Medios database.

The media has given violence greater coverage than other issues, some of which are far more important. For example, poverty, which is a problem affecting half the population, received much less coverage in the newspapers analysed. Obesity, one of the main challenges facing public health, accounted for a derisory average of 60 notes per year during the period.

Graph 3. Press coverage per topic in three major national papers, 2007-11

This is not exactly new in the media world: numerous studies (Altheide, 1982, 1987; Nimmo & Combs, 1985; Nacos, 1994; Weimann & Winn, 1994) have encountered ‘convincing evidence of the media’s tendency to over-cover terrorist incidents at the expense of other equally important, or more important, news’ (Nacos, 2011).

Another interesting finding is the lack of substantial differences between the coverage of the topics analysed among the three newspapers. Despite the fact that they are considered ideologically biased, there are no differences in the amount of attention they pay to any of the issues considered.

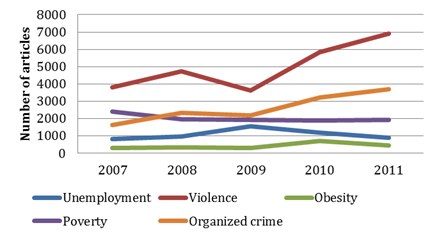

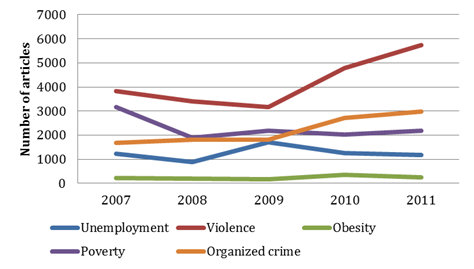

Graph 4. Press coverage per topic in Reforma, 2007-11

Slight disparities are found regarding the coverage of poverty, which is less important (according to the number of news articles devoted to it), in Reforma, a right-wing daily, while it is covered more in La Jornada, the left-wing paper. Another outcome, though predictable, is that unemployment gets the highest number of hits in 2009, when the financial crisis had its greatest impact on the economy.

Graph 5. Press coverage per topic in El Universal, 2007-11

Graph 6. Press coverage per topic in La Jornada, 2007-11

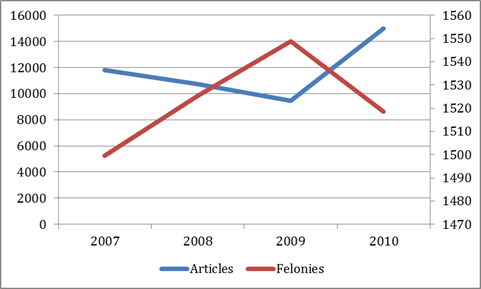

It is clear that violence and drug trafficking have got more coverage than other pressing problems. However, some might argue that the amazing increase in violence alone can explain the huge increase in the number of news articles devoted to the issue. Unfortunately, this does not seem to resist a quantitative test. By contrasting the number of homicides with the quantity of news articles published between 1997 and 2010, it cahn be seen that there is only a weak relationship between actual violence and its coverage.

Graph 7. Number of articles on violence and homicide rates, 2007-11

Graph 8. Number of articles on violence and the number of felonies

These figures suggest that there is a media rationale other than pure reporting of the facts behind the prevalence of violence reporting in the major Mexican papers. As stated in the previous sections, the disproportionate attention paid to violence supports the hypothesis that Mexican media outlets have sought tragedy, sensation and drama in the news just as they do in entertainment. The data show that the media has covered violence since President Calderón launched his assault on drug-trafficking organisations regardless of the actual levels of violence.

Despite the intrinsic relevance of an increase in violence, it would be naïve to think that media coverage does not influence the way people think about certain issues. ‘Media are spaces in which many social actors act (including journalists) and can become themselves collective actors…’ (Page, 2000, p. 29). The power of the media as agenda setter has been extensively discussed in the social sciences, but has not been applied to the analysis of the mass-mediated phenomenon of organised crime in Mexico.

Previous research has consistently established that the magnitude of terrorism coverage affects the public agenda (Nacos, 1996, 2007). As the number of news items on terrorism increases, the public’s perception of terrorism as a major national problem also increases. Without performing a thorough statistical analysis, it is reasonable to argue that perceptions of violence in Mexico have also been affected by the media’s coverage.

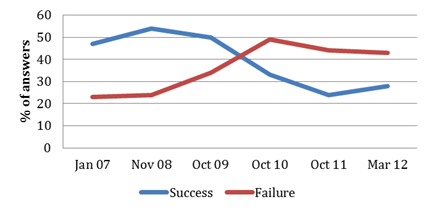

According to a recent poll conducted by Consulta-Mitofsky (March 2012), public security is the single issue that Mexicans consider their most pressing problem. It accounts for 44% of the answers (in 2007 the proportion was 34%, and reached 50% in 2011). The media’s effect on citizens’ perceptions can be an explanation for the gap, found by Díaz-Cayeros et al. (2011), between the actual victim rate and the public’s fear of being the victim of a crime.

Table 3. Actual crime rates and public fear of being a victim

| Crime | Actual victims (%) | Afraid of being a victim (%) |

| Kidnapping (not express) | 1 | 81.8 |

| Kidnapping (express) | 1.3 | 82.8 |

| Affected by criminals’ crossfire | 3.1 | 83.4 |

| Car robbery | 10.1 | 84.2 |

| Phone extortion | 25.7 | 81.3 |

Source: Díaz-Cayeros (2011).

Again, the data suggest that organised crime is achieving at least part of its goals. The organisation are being acknowledged in the press, through which they gain recognition from potential recruits and competitors. Their messages are also being carried by the press, not only by publishing the content of their banners, in violation of the agreement signed by the media in 2011, but also by spreading fear and criticising the government at the core of the debate on the war on drugs. Violence has become the favourite indicator to assess the success or failure of a government.

However, the increase in news articles is far from being the only change in the way the media report violence. There has also been another major transformation: while murders were usually included under crime, now they are placed under politics. And this has not been the last change in the media’s coverage of violence. The narrative used by the press to report on violence and the very essence of criminal behaviour is also different. The following section is a qualitative analysis of the media’s coverage of the war on drugs in Mexico.

The Cartels’ Victory: Reporting Military Action and Cartel Retaliation

After the surge in the number of killings presumably related to the war on drugs, some analysts have pointed out that criminal organisations and their leaders have become more violent (Ríos, 2011). However, there is little evidence to support this, against the alternative of assuming that violence is a result of changing conditions in the underworld of organised crime. Beheading, dismembering, burning to death, asphyxiating and all sorts of torture have long been part of the organised crime scene in Mexico.

Drug cartels have always killed their enemies in a bloody and cruel way; what is different nowadays is that they also seek greater publicity for their murders. They not only torture their victims but also expose their mutilated bodies, and usually leave written messages over the corpses addressing the government, public opinion or their opponents. There has been a change in the levels of publicity under which they carry out their criminal activities. As argued in this paper, they have not just resorted to a particular kind of violence but also –although not exclusively– intended it to make the news. This is what could be called mass-mediated organised crime.

Drug traffickers have changed their strategies; they now act differently. To some extent, as the Mexican government has argued, they have resorted to violence as a result of the competition between different groups of organised crime. Yet the ways in which they seek media attention suggest the tacit objective of reaching an audience. This highlights the importance of the media in the fight against organised crime. As in the reporting of terrorism elsewhere, the Mexican media face an uneasy challenge in defining the way they report violence.

Criminal syndicates have at least three concrete media-related goals: (1) attracting attention towards competing violent groups; (2) gaining respect and sympathy from the population –or at least a fraction of it–; and (3) building up a quasi-legitimate status. As argued before, respect and sympathy may help the efforts of criminal organisations to recruit new personnel as well as to deter the government’s law enforcement operations.

This section addresses the issue by analysing the way in which major newspapers in the country have covered some of the more important operations against organised crime and the criminal response to the government’s law enforcement efforts. By analysing the coverage of the war on drugs, it seeks to shed light on the way news organisations and organised crime are shaping Mexico’s public opinion and public policy.

A qualitative analysis has been made of 89 news articles written about three major military operations in which drug leaders were arrested and cartels retaliated violently: (1) the capture of Osiel Cárdenas in Tamaulipas in 2003; (2) the arrest of Arnoldo Rueda in Michoacán in 2009; and (3) the recent arrest of Erick Valencia in Jalisco in March 2012 (see Table 3).

All three events involved the action of the military in security tasks and they were associated with violent responses from organised crime. In this respect, the episodes show how the media communicate the government’s take on organised crime, as well as the criminals’ response to the operations.

Table 4. Events and number of articles analysed (El Universal, La Jornada and Reforma)

| Event (arrest of) | Date | Days of coverage analysed | Number of news articles | % of total |

| Osiel Cárdenas | 14/III/2003 | 3 | 10 | – |

| Arnoldo Rueda | 10/VII/2009 | 4 | 23 | 100 |

| Erick Valencia | 9/III/2012 | 4 | 46 | 100 |

Osiel Cárdenas was one of the main bosses of the Mexican criminal syndicates at the time of his arrest. He was captured in his house at Tampico, Tamaulipas, in northern Mexico. Shortly after his arrest, however, gunmen at his service tried to release him by attacking the military convoy that was driving him to the prosecutor’s office. During the enforcement operations, conducted by the military, the soldiers faced violent opposition from the criminal organisation knows as the Cártel del Golfo.

Articles over the following days highlighted the apprehension of one of Mexico’s most important organised crime bosses. Then they narrated how a group of gunmen had tried to rescue their leader but had been unable to do so. In the shootout there were three soldiers wounded, as mentioned in almost every article. Six members of the criminal group were also shot, but they only appear in three of the 10 articles reviewed. Also, only one article mentioned a girl who received a gunshot wound while walking out of her school, near one of the shootouts.

The criminal group’s violent response was presented in some news items as an act of desperation, aimed at liberating the mafia boss. Also, the final component of almost every news item covering the event (nine out of the 10) is that they provide information about who was detained, what his criminal activities were and his relevance within the organisation.

The arrest of Arnoldo Rueda was also followed by a violent response from La Familia Michoacana, a criminal organisation based in the western state of Michoacán. The retaliation in this case was more violent and longer-lasting than for Osiel Cárdenas, with over four days of intermittent violence.

The reports in this case gave a greater coverage to the violence itself. Most sported headlines such as ‘Attacks checkmate Michoacán’. Only 10 of the 23 articles mentioned the arrest, 16 were primarily concerned with the fact that a criminal group had attacked the armed forces, seven mentioned that there were civilians wounded and killed during the shootouts and nine covered the death of six soldiers and police officers during the fighting.

Finally, the last event serves to highlight one of the most interesting, troubling and challenging findings of this paper. The capture of Erick Valencia, leader of the Nueva Generación (New Generation) cartel occurred in Zapopan, Jalisco, in the metropolitan area of Guadalajara. The level of violence was similar to Osiel’s arrest, but a relatively new tactic was employed, the narcobloqueo (described at the beginning of this paper). Media attention was thus far greater.

As in Rueda’s case, it was not Valencia’s actual arrest that was the most important news, but neither was the criminal organisation’s violence the focus of the report. Instead, a surprising 32 of the 48 articles published during the days after the arrest highlighted the fact that the army’s operation ‘unleashed chaos’. Reading each article in depth, the impression is that the Mexican military should perhaps have considered not hitting the cartel and thereby preserved peace in the city.

Most of the accounts of that day in Guadalajara deal with the chaos created by the blocking of streets and main intersections, the shootouts around the city and the deaths of two innocent people and two members of the criminal organisation. They also draw attention to the fact that the army’s operation to arrest the criminal was conducted in an urban area, where civilians were put in danger.

This is a major change between the first and last event: in the past, the media reported violence as a deliberate action of the drug traffickers; now, violence is attributed to the action of the law enforcement agencies. In this respect, the media have contributed to building a narrative that is beneficial to drug-trafficking organisations, according to which violence is understood to be a by-product of police action instead of organised crime. In doing so, the media are affecting the way people think about the war on crime while limiting the policy alternatives for future governments.

Debate about government action against organised crime has almost entirely focused on the skyrocketing homicide figures. As criminal organisations continue to fight the government as well as each other and violence spreads around the country, the President is held to have failed in his approach to the problem and, hence, that he should change strategy.

Regardless of the validity of such a statement, it is a fact that organised crime has succeeded in creating a climate of opinion that is much more favourable to reducing law-enforcement operations than to increasing them. This matches the argument that organised crime has used the media to influence public opinion. The Tenth National Poll of Citizens’ Perceptions about Public Safety shows some interesting data. Not only is security at the top of the issues perceived to be problematic, but the public also disagrees in the way policy is being conducted.

Graph 9. Public perception of the fight against organised crime

In the narrative of war built up by the government and exploited to the limit by the media, the perception is that the State is losing the fight against criminal organisations. While the public is not against battling criminal syndicates, it deeply disapproves of failure. This negative perception, in addition to the widespread narrative that violence has increased as a result of the President’s actions– might even cost his party the next presidential election.

Conclusions

In any functional democracy, it is reasonable to find a strong relationship between policy and public opinion. In contemporary democracies, moreover, public opinion is inexorably linked to the mass media and to the communication strategies of both the government and opposition. This is the political context in which Mexico is fighting a deadly battle against the most powerful and well-funded drug-trafficking organisations in the world. According to Forbes, Joaquín ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán, one of Mexico’s most important capos, is also one of the world’s wealthiest men.

While violence actually has increased, it is also true that the media have given the phenomenon a disproportionate amount of coverage, at the expense of equally or even more pressing problems for society. It is surprising that the number of news articles related to organised crime have not increased in line with the growth of violence, but only in response to the President’s war on drug-trafficking organisations.

Even more striking, this paper shows that the media have turned from reporting enforcement operations as part of the war on crime to covering them as the source of violence. While the violent response of criminal organisations to military action were reported as ‘desperate efforts’ in 2003, they have increasingly been presented as the proof of their power. Previously, violence was attributed to the criminal organisations themselves, but now it is reported as though triggered by the State’s law enforcers.

Although drug traffickers are not terrorists who seek media publicity to advance a political cause, they do have important media-related goals as they seek to have an impact on public opinion and thereby affect policies. By undermining the government’s reputation, many drug lords think that the aggressive policies implemented against them can be annulled by a change in the administration.

However, this is not to say that drug-trafficking organisations and the media are in any sort of agreement against the government. That is out of question. But the data reviewed in this paper do show that it would be important to re-think the way the two parts interact and that the consequences of their factual relationship are negative.

The implications for security policy are not to be disregarded. The next government will have the imperative of reducing the level of violence and, while withdrawing the army does not seem a viable alternative, it might have an incentive to reduce the pressure on organised crime. The media have been instrumental in creating this perception and will continue to be at the centre of the issue in the future.

Edgar Moreno Gómez

Graduate student of Public Administration at Columbia University and formerly chief speechwriter in Mexico’s Ministry of the Economy and speechwriter to the President of Mexico

References

Barkho, Leon (2006), ‘The Arabic Aljazeera Vs Britains’s BBC and America’s CNN: Who Does Journalism Right?’, American Communication Journal, vol. 8, nr 1.

Bernays, Edward (1947), ‘The Engineering of Consent’, Annals of the American Academy of Political Science, vol. 250, p. 113-120.

Blancornelas, Jesús (2002), El Cártel, Plaza y Janés, Mexico DF.

Bloch-Elkon, Yaeli, Brigitte Nacos & Robert Shapiro (2007), ‘Post-9/11 Terrorism: Threats, News Coverage, and Public Perception in the United States’, International Journal of Conflict and Violence, nr 1, p. 105–26.

Bloch-Elkon, Yaeli, & Brigitte Nacos (2012), ‘The Media, Public Opinion, and Terrorism’, in Robert Y. Shapiro (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of American Public Opinion and the Media, Oxford Handbooks.

Bok, Sissela (1998), Mayhem: Violence as Entertainment, Perseus Books.

Cottle, S. (2006), ‘Mediatizing the Global War on Terror: Television’s Public Eye’, in A.P. Kavoori & T. Farley (Eds.), Media, Terrorism, and Theory, Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham, MD.

Díaz-Cayeros, Alberto (2011), ‘Living in Fear: Mapping the Social Embeddedness of Drug Gangs and Violence in Mexico’, Violence, Drugs and Governance: Mexican Security in Comparative Perspective, Stanford Conference.

Felshtinsky, Yuri (2008), The Age of Assassins: The Rise and Rise of Vladimir Putin, Gibson Square, London.

Gambetta, Diego (1996), The Sicilian Mafia: The Business of Private Protection, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Glenny, Misha (2008), McMafia: Journey Through the Global Criminal Underworld, Vintage, London.

Handelman, Stephen (1995), Comrade Criminal: Russia’s New Mafiya, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT.

Nacos, Brigitte (1994), Terrorism and the Media, Columbia University Press, New York.

Nacos, Brigitte (2000), ‘Accomplice or Witness? The Media’s Role in Terrorism’, Current History, nr 99, p. 174-178.

Nacos, Brigitte (2007), Mass Mediated Terrorism: The Central Role of the Media in Terrorism and Counter-Terrorism, Rowan & Littlefield, Lanham, MD.

Norris, Pippa (2004), ‘Global Political Communication: Good Governance, Human Development, and Mass Communication’, in Frank Esser & Barbara Pfetsch, Comparing Political Communication, Cambridge University Press.

Sanderson, Thomas (2004), ‘Transnational Terror and Organized Crime: Blurring the Lines’, SAIS Review, vol. XXIV, nr 1.

Ríos, Viridiana (2010), ‘To Be or Not to Be a Drug Trafficker: Modeling Criminal Occupational Choices’, unpublished manuscript.

Ríos, Viridiana (2011), ‘Why are Mexican Mayors Getting Killed by Traffickers?”, paper presented at the MPSA Annual Conference, Chicago, IL.

Steward Ewen (1996), A Social History of Spin, Basic Books, New York.

Weimann, G., & C. Winn (1994), The Theater of Terror, Longman, New York.

Zaller, John (1998), ‘Monica Lewinsky’s Contribution to Political Science’, Political Science and Politics, vol. 31, nr 2, p. 182-189.