Also available the Spanish version: El proceso independentista catalán: ¿cómo hemos llegado hasta aquí?, ¿cuál es su dimensión europea? ¿y qué puede ocurrir?

Updated: 19 January 2018.

Some background information on Catalonia as part of Spain

- As in Canada and Belgium (and, to a certain extent, the UK), centre-periphery tensions constitute a permanent feature of Spain’s political landscape.

- Spain undertook early and effective state-building in the 15th-18th centuries but a late and more troubled nation-building process took place in the 19th and 20th centuries, with strong regional identities in competition, particularly in Catalonia and the Basque Country. The latter were never ‘independent’ in the modern sense, being parts of a composite monarchy, but they do have historically distinctive traitss.

- Nevertheless, Spain is one of the very few cases in Europe in which national integrity has been successfully preserved: no territorial change has occurred in the past 200 years (colonial possessions aside, which were not an integral part of Spain).

- Despite its initially conservative bias, peripheral nationalism became partly associated with freedom and the fight against central authoritarianism. Regional self-government was linked to democracy, with devolution to Catalonia occurring in two democratic periods (1914-23 and 1931-39) and being suppressed under the dictatorial regimes of Generals Primo de Rivera (1924-30) and Franco (1939-75).

- Nationalism in Catalonia was linked to both the peasantry and part of the modernising bourgeoisie. The region simultaneously experienced industrialisation (it borders France, with a weak Spanish state but a large internal market) and a so-called ‘cultural renaissance’.

- After its transition to democracy in the late 1970s, Spain can be considered a federation in all but name, with 17 autonomous communities having extensive devolved powers, guaranteed by the Constitutional Court.

- Although the 1978 Spanish Constitution states that sovereignty resides with the Spanish people as a whole, it also specifies that regions and ‘nationalities’ have a right to political autonomy.

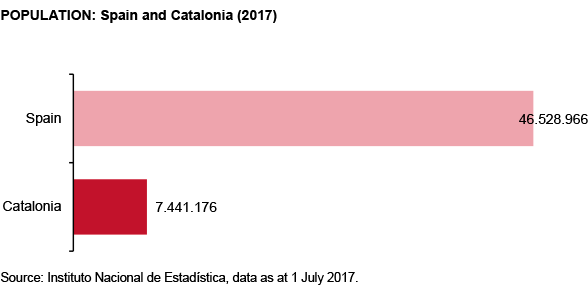

- In the early 20th century, Catalonia only accounted for 10.5% of Spain’s population. Nevertheless, Catalan economic growth attracted large-scale immigration from the rest of Spain, especially from the 1950s. In 1981 Catalonia’s population accounted for 15.8% of Spain’s total, rising to 16.1% in the present day.

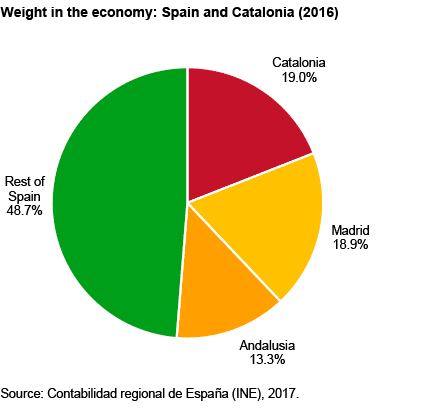

- Catalonia’s relative prosperity has led its GDP to account for 19% of Spain’s wealth.

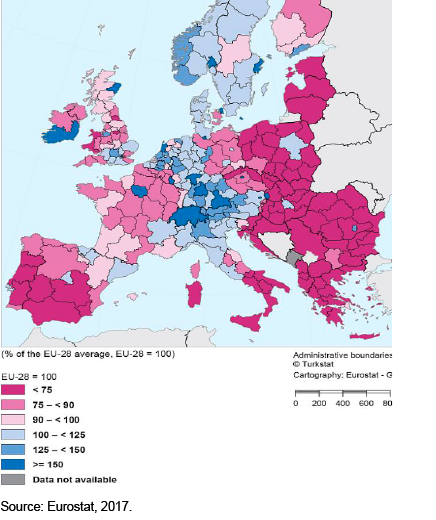

- Catalonia is today more prosperous than Spain as a whole, at around 20% above the national average, and it is also above the European average and ahead of neighbouring French regions. In 2016 Catalonia was the source of 25.6% of total Spanish exports and the destination of 20.7% of total gross foreign investment.

- Catalonia’s contribution to Spain’s global presence (as calculated by the Elcano Royal Institute, aggregating projection abroad in economic, security and soft power terms) is also high at 19.6% of the total, second only to Madrid.

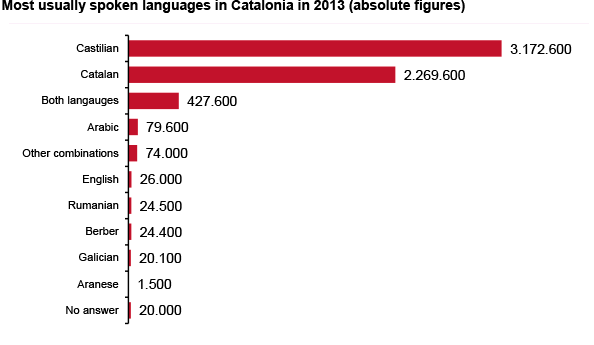

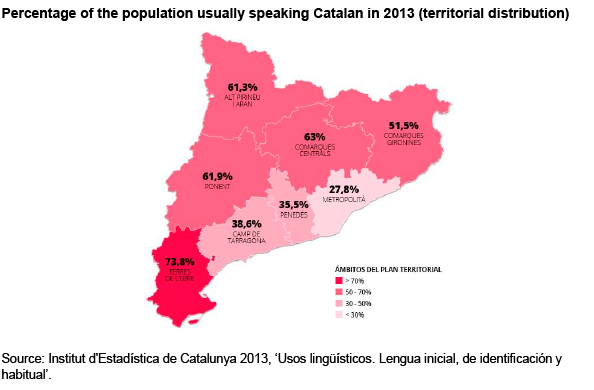

- Contrary to a widespread perception, the Castilian (Spanish) language spoken more in everyday use than Catalan. In Barcelona and other urban areas, 75% of the population usually speak Spanish, while Catalan is employed to a greater extent in the countryside. A full 99% of Catalans can understand Spanish and 95% are familiar with Catalan.

- The region enjoys a high degree of self-government regulated by the 2006 Catalan Statute. Despite the Constitutional Court ruling in 2010 that certain articles were unconstitutional (on the organisation of an autonomous judiciary and certain political effects of self-recognition as a ‘nation’), Catalonia has extensive powers in:

Civil law, police, culture, language, education, health care, agriculture, fisheries, water, industry, trade affairs, consumer affairs, savings banks, sports, historic heritage, environment, research, local government, tourism, transport, media and a wide range of other issues.

- Catalonia also has its own tax collection system, although most tax revenues –and social security benefits– are mainly controlled by the central government. Although foreign policy is an exclusive power of the central government, the regional government has its own external action service and a strong network of offices abroad.

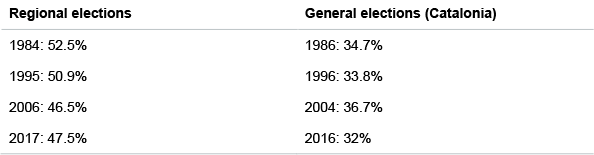

- The Catalan nationalist parties’ share of the vote has remained fairly stable and even tended to decline:

Factors explaining Catalonia’s bid for independence

- Until the mid-2000s Catalan society was roughly split into three equal parts:

a) A group comprising the rural population and the urban middle and upper classes, who feel that Catalonia is a stand-alone nation due to its distinctive language and culture and greater prosperity than the rest of Spain.

b) A sociologically less cohesive and less mobilised group made up of the descendants of immigrants from other Spanish regions who retain a predominantly Spanish identity and have Castilian as their mother tongue.

c) Those with a shared Spanish-Catalan identity who tend to be truly bilingual.

- This mixed and complex sociological structure resulted in the dominance in Catalonia of two big moderate parties: the Catalan branch of the Spanish Socialist Party (PSOE-PSC) to the centre-left and the regionalist Convergencia i Unió (CiU) to the centre-right, the latter being in office for most of the period 1980-2010.

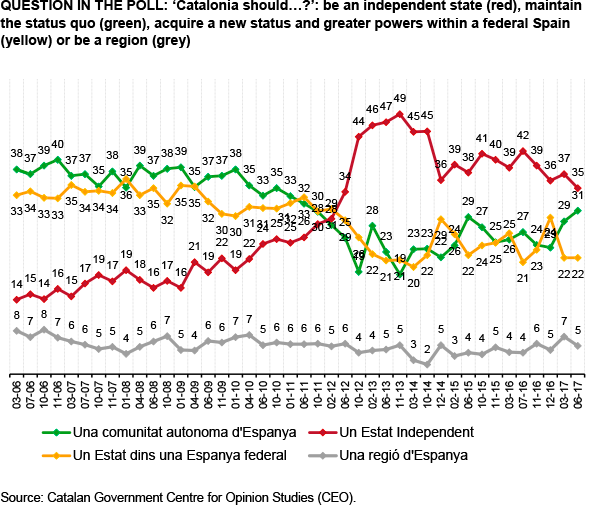

- Before 2010 it was unusual for more than 20% of Catalans to support independence.

- The political status quo changed around 2010 for a number of reasons, some of them resulting from long-term developments and some due to short-term factors.

- External long-term factors:

a) Globalisation and EU integration can encourage secession: free trade and international governance mean that states no longer need to be big to exploit economies of scale. The economic and political risks of independence are lower in a supranational area such as the EU.

- Internal long-term factors:

a) The implementation from the 1980s by the Catalan authorities of an outright process of building up a national identity distinct from the Spanish (based on the education system and regional television broadcasts).

b) Tension with the Spanish national project after 1978, despite moderate nationalists contributing to Spanish governance from 1977 to 2012: a feeling of mutual distrust.

- External short-term factors:

a) In 2012 the Scottish National Party (SNP) negotiated a binding referendum for Scottish independence, setting out a plausible and respectable precedent for democratic secession within Europe.

b) Stability measures linked to the Eurozone crisis –EU-led austerity and increasing central control over regional finances– encouraged populist messages of fiscal rebellion (similarly to UKIP and Lega Nord).

- Internal short-term factors:

a) From 2008 onwards, Spain (including Catalonia) underwent a deep economic, social and political crisis, with high unemployment and a significant impact on the middle class, nationalism’s traditional electoral platform. There was a swift erosion in the Spanish political system’s legitimacy.

b) In 2010 the Spanish Constitutional Court, following an appeal by the centre-right PP (then in opposition), partly disallowed the Catalan Autonomy Statute in 2010, which had been approved in 2006 by a referendum in the region.

c) The PP replaced the Socialists in power in Madrid in late 2011, giving rise to a more conservative and centralist adversary. Secessionism, as in Scotland, rebranded itself in a more progressive guise to widen its appeal.

d) The mobilisation of nationalist civil society and nationalist elite polarisation fed off each other, with the latter entering a headlong competitive spiral of radicalisation that led to a subsequent rise of secessionism in 2012.

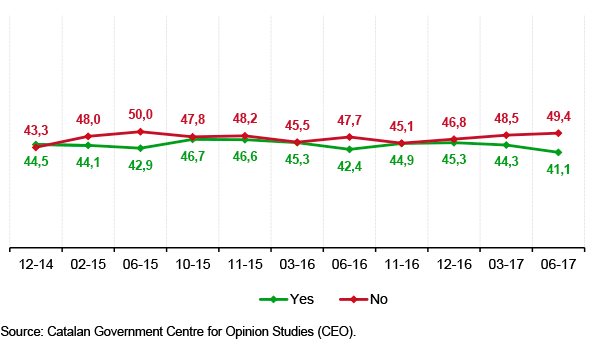

- Support for secessionism reached a peak of 49% in 2013, subsequently declining. The most recent survey by the Catalan government’s Centre for Opinion Studies (CEO), conducted in July 2017, shows that only a minority of Catalans (35%) support independence (see Graph overleaf).

- In recent surveys, 76% of Catalans actually identify with Spain. Support for Catalan secession is far from overwhelming.

- QUESTION IN THE POLL: “Catalonia should…?”: be an independent state (red), maintain the status quo (green), acquire a new status and greater powers within a federal Spain (yellow) or be a region (grey)

Secession and EU membership

- The existence of the EU itself may be an encouragement to secession: ‘Independence in Europe’ is the slogan of Scotland’s SNP and ‘Catalonia, a new state in Europe’ was the slogan of the huge September 2012 demonstration in Barcelona, which marked the beginning of the current independence process.

- However, since Catalans and Scots wish to remain in the EU, its rigid rules on enlargement are an obstacle:

‘When a part of the territory of a Member State ceases to be a part of the state, eg because that territory becomes an independent state, the treaties will no longer apply to that territory’ (EC President R. Prodi, 2004).

‘A new independent state would, by the fact of its independence, become a third country with respect to the EU and the Treaties would no longer apply on its territory’ (Letter to the UK House of Lords from EC President J.M. Durão Barroso, 2012).

- In response to the clear position in Brussels, secessionists proposed the possibility of simultaneous or, at least, ‘fast track’ accession:

Negotiations on membership can take place during the period between a ‘yes’ referendum and the planned date of independence (no need to leave and apply for readmission).

The EU could adopt a simplified procedure for accession negotiations, beyond the traditional proceduree.

- In any case, such an agreement would depend on a sufficient political will and be subject to unanimous ratification by all member states. The necessary consensus is unlikely for Scotland and impossible for Catalonia (considering the unilateral character of the independence process, which would prevent the recognition of the new state by the international community and, certainly, by the EU’s member states).

- The reasons against allowing seceding territories to join the EU are not only the result of juridical considerations or of the political rejection of countries such as Spain but also of the refusal to contemplate such a move by European institutions and the rest of the Union’s member states.

- There are, in addition, a number of specific reasons:a) The possibility of a domino effect in other regions (Flanders, northern Italy, Corsica, Hungarian-speaking minorities, etc) that would weaken the Union’s member states or fragment them to the extent that the current territorial model would be unviable.b) The legitimation of de facto situations in Eastern Europe (Transnistria, South Ossetia, Abkhazia, Crimea, etc.) or even within the EU itself (the so-called Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus). The ripples could also destabilise Bosnia-Herzegovina or Kosovo.

- But there are also more general and political reasons. European integration is an avowedly antinationalist project and only in exceptional circumstances could it feel any sympathy for these types of processes. This could have been the case with Scotland, but is certainly not with Catalonia.

Why are Catalonia and Scotland different? (1/5)

- The main differences commonly mentioned in Spanish political debate are four:

a) The 2014 independence referendum held in Scotland in 2014 was agreed with London, in sharp contrast with the dominant unilateralism in Catalonia. The Catalan bid has ignored the strong opposition of the Spanish parliament.

b) The Scottish government was respectful of the British legal order while the Catalan case has involved flouting the rule of law, both in Spanish (several decisions of the constitutional court have been disregarded) and European terms: ‘The Union shall respect their essential state functions, including ensuring the territorial integrity of the state…’ (article 4.2 Treaty).

c) The Spanish constitution declares that national sovereignty belongs to the entire Spanish people. For its part, the UK has retained some elements of an explicitly multinational state (composite monarchy).

d) Without Catalonia there would be no Spain since the Spanish national project would be voided. This is similar to the Canadian case regarding Quebec, while Scotland is seen in the UK as ultimately more dispensable.

- There are other lesser-known but relevant political differences:

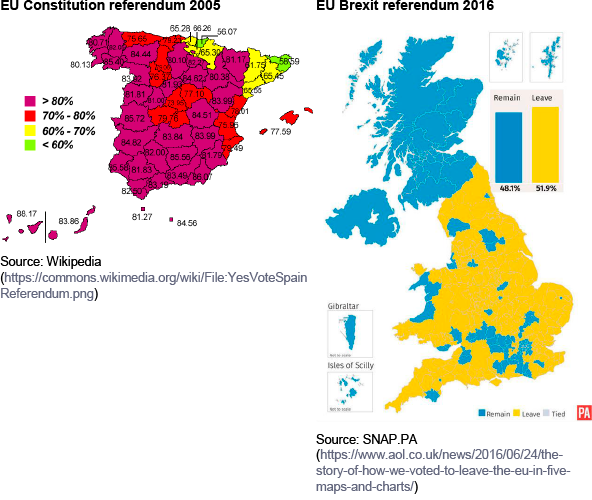

a) Spain’s strong Europeanism, in contrast to the UK’s Euroscepticism. While Scotland is one of the most pro-European parts of the UK, Catalonia is one of Spain’s least Euro-enthusiastic regions.

b) Scotland’s relatively unaggressive national identity contrasts with the high potential for conflict between social groups inherent to the Catalan situation, where the Catalan and Spanish national projects compete for absolute loyalties to language and identity. The increasingly radical character of the independence process has slowly but steadily mobilised the elements in Catalan Society that are against separatism.

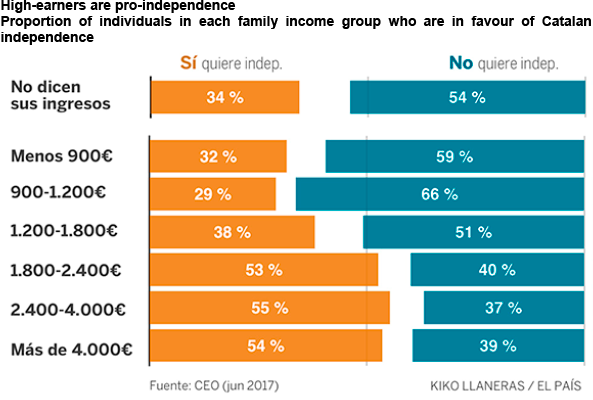

c) A ‘Revolt of the Rich’?: In Scotland (a region less wealthy than the rest of UK) the richer the area the higher the vote to remain, and the more deprived the greater the pro-independence vote. Conversely, Catalonia is not only one of the most affluent Spanish regions but, also, secessionism has more support among higher-income segments. Thus, it can be perceived as selfish and rejecting solidarity.

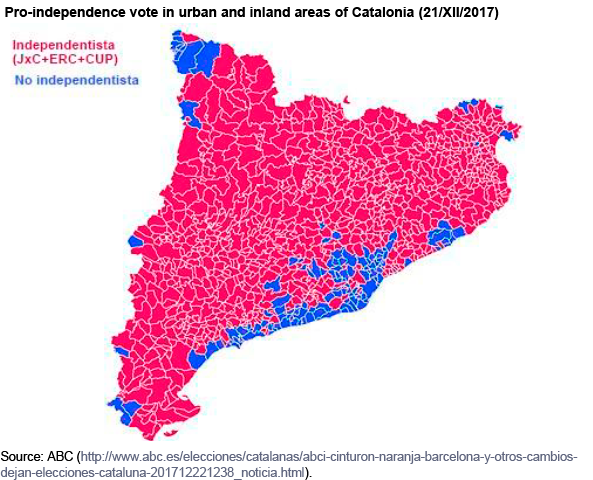

d) While Scottish independence is viewed more favourably in big cities, in Catalonia the territorial divide is the reverse: rural areas register a majority in favour of independence, with urban areas having a majority against:

Attempts to ‘internationalise the conflict’

- Internationalising the secession issue has become a key factor in the strategy of the Catalan independence movement. As both the Spanish parliament and the Constitutional Court have clearly determined that Catalonia has no right to self-determination, the only option has been to attempt to convince outside players to put pressure on Madrid to accept a referendum.

- The underlying logic is sometimes idealistic: despite the dominant paradigm of territorial integrity, the EU and the major powers will support the ‘Catalan democratic mandate’. But secessionism has also appealed to realism: foreign governments and financial markets cannot afford a chaotic default given Spain’s public-debt burden and the importance of the Catalan economy.

- The Catalan bid has so far received no foreign support: Merkel, Hollande, Obama, Cameron, May, Macron, Trump, Juncker, Tusk and all international leaders except Venezuela’s Nicolás Maduro explicitly support a united Spain and the rule of law.

- It is highly unlikely for international leaders to change their minds given their strong reluctance to support or pragmatically accept unilateral secession, especially since the independence movement lacks a clear majority and Catalan society is so divided.

- Foreign support for Catalan independence is limited, and would be practically nil if the process were to be unilateral. Nevertheless, some international media and segments of European public opinion are in favour of the Spanish government being more amenable to dialogue and even of a solution that might consider a referendum specifically addressing secession.

- According to recent polls, Catalan public opinion overwhelmingly (at around 70%) favours a referendum mutually agreed with the state. However, it is more than debatable whether this involves any strong preferences one way or the other beyond wanting to be directly involved in any decision that might be taken.

- On the other hand, recent surveys suggest that the percentage of Catalans in favour of a solution not involving an independence referendum but rather constitutional reform and improved self-government is also around 70%. Such a possible solution is even favoured by a majority of those who advocate independence. Rounding off a possible agreement with a referendum could conceivably be a way to reconcile the two sides and achieve a constitutionally-based solution.

- In any case, it is debatable whether an independence referendum is the most appropriate way to resolve such a complex and divisive issue.

- Referendums to gauge support in entrenched problems (and not as a way to accept or reject mutually-agreed solutions) are highly divisive in deeply fissured societies. They have rarely been resorted to in similar situations, such as Belgium and Northern Ireland –where the political divide is based on sharp differences in identity, language or religion–. When they have been held (as with, for instance, the Northern Ireland border poll of 1973), the experience has been traumatic, bringing to the fore or even aggravating sectarian hostility.

- Given the strong correlation between language and political preferences on the issue of Catalan independence, a referendum may become a divisive zero-sum mechanism, in which a small —and probably unstable— majority imposes its preferences in a way that cannot easily be reversed. Divided societies need power-sharing strategies and consociational arrangements to defuse conflictsy.

Latest developments and the situation following the December 2017 elections

- According to the most recent polls, when Catalans are asked a binary question (‘yes’ or ‘no’ to secession), a majority are against, but society is riven down the middle:

- Over the course of the autumn of 2017 the independence movement saw its strength confirmed but it also became evident that it would be unable to fulfil its unilateral strategy given the realisation by its own leaders that they lacked majority support and had no effective control over the region’s territory.

- The tense situation has prompted a heightened social division and led to a negative impact on the Catalan economy: a sharp slowdown in foreign investment, an increasing gap in growth with the rest of Spain and the exit of more than 3,000 companies, which have moved their head offices elsewhere. Some analysts even refer to a ‘Montreal effect’, in reference to the city’s loss of prosperity to Toronto following the surge in support for the Quebec independence movement in the 1990s.

- From an international point of view, no country supported the Catalan regional government when it announced its plans to proclaim independence unilaterally or, alternatively, to seek foreign mediation to resolve the crisis. In fact, there has been outright unanimity among foreign governments and multilateral organisations (including, very significantly, those of the EU) in support of Spain’s interpretation of its own constitution. No one believes in remedial secession.

- Although the justification and feasibility of Catalan secession are both very weak, the Catalan independence movement did garner some international sympathy based on the events that occurred during the attempted referendum (which had been declared illegal by the Constitutional Court) of 1 October, when the declared turnout was of only 40% but the occasion was marred by some violent episodes prompted by the intervention of the National Police and the Civil Guard.

- Moving beyond the comparison with Scotland, the pro-independence movement resorted to other far less adequate examples, such as Kosovo and Ukraine. In the latter case, the idea was to give legitimacy to the possibility of mass mobilisations in the streets on the Maidan model, despite the disturbing undertones in the comparison (violence) and the obvious differences.

- Coinciding with the unilateral declaration of independence finally proclaimed on 27 October 2017 by 70 of the 135 members of the Catalan government, the Spanish government set in motion article 155 of the Constitution (with the approval of the Senate by 214 in favour and 47 against). This involved suspending self-government, dissolving the Catalan government and the calling from Madrid of new regional elections for 21 December.

- The election campaign took place under exceptional circumstances, including the flight to Brussels of the deposed Catalan premier and the remanding in custody on charges of rebellion of several nationalist leaders who were candidates. Although applying the coercive measure contemplated by article 155 was less disruptive than expected, partly because of its limited objectives and time-frame, Catalan society remains as polarised as before.

- Nevertheless, despite the still radical rhetoric, the pro-independence parties seem willing to dispense with their failed unilateral option.

- The election results confirm a highly fragmented political scenario

- As regards secession, its supporters have again shown their strength but have also revealed their limitations in having failed by far to achieve a qualified majority that would allow it to reform the statute of autonomy of Catalonia and gaining less than 50% of the vote.

- The most voted individual party was Ciudadanos (C’s, founded only 15 years ago on an explicitly antinationalist platform), although the three nationalist parties combined gained an absolute majority and therefore the possibility of forming a government.

- Comparing the voting averages for the 30-year period 1980-2010 with the latest elections, support for Catalan nationalism (which was previously largely pragmatic but has now become radicalised and advocates an open break) has hardly changed, having moved from 47.8% to 47.5%. To the contrary, support for non-independence Catalan sentiment (advocating a greater degree of self-government within Spain) has dropped from 36% to 21.5% while antinationalism (PP plus C’s) has risen from 11.1% to 29.5%.