Abstract

The EU is a world player by virtue of its population and economic power. The Treaty of Lisbon introduced far-reaching changes in its external action, allowing it to become a more effective actor on the world stage. However, the financial instruments available for it to implement its external policies are very limited. Furthermore, the euro-zone crisis and its impact on the Union’s national budgets provide a major stimulus to consider the EU’s external action as an alternative to those of individual Member States. EU institutions and Member States are currently negotiating the multiannual financial frameworkfor 2014-20 (MFF 2014-20). The outcome of the negotiations will have important implications for the Union’s external relations and for the role it can play on the global stage.

This Working Paper will analyse the negotiations and the main conflicting issues and present an insight into what might be the likely outcome of the process. It will also consider the suitability of the financial instruments available to bridge the existing gap between the EU’s ambitions, expectations and capabilities in the external sphere.

Introduction

The EU is a world player by virtue of its population and economic power. The Treaty of Lisbon introduced a number of far-reaching changes in order for the Union to become a more effective, more coherent and more capable actor on the world stage. Europe’s citizens consider external affairs to be one of the main issues to be addressed by the EU. Furthermore, recent international developments have made it clear that the EU still lacks effective short- and medium-term instruments to contribute to conflict resolution.

However, the financial instruments with which the EU carries out its external policies are very limited. Their maximum amount and composition are set out in the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF). For 2007-13, the financial resources for external action under heading 4 –‘EU as a global player’– account for roughly 7% of the EU’s total budget, which itself accounts for only 1% of its GNP.

The resources for the financial instruments of the next few years will finally depend on the outcome of the ongoing negotiation of the MFF 2014-20, which will not only define the overall budget but also the broader priorities for the EU’s external action for the coming seven years. Although there is renewed debate on the EU budget’s role in overcoming the crisis, the current negotiations seem to concentrate once again on the traditional conflict between net beneficiaries and net contributors. The negotiations started with the usual discussion on the budget’s overall ceiling and the main items of expenditure (CAP and Cohesion Policy). So far, Member States and EU institutions appear to have avoided discussing both the financing and the shape of the EU’s future foreign policy.

Nevertheless there seems to be a consensus among Member States and EU institutions that external action can provide a significant added value, such as a stronger negotiating position and greater political leverage. Thus, the legal basis of the EU’s external action has already been reinforced. The Treaty of Lisbon clearly says that the EU aims to become a potential actor on the global scene.

This Working Paper looks at the challenges and deficits of the EU’s external action, in addition to the European Commission’s (EC) proposal regarding the financial instruments for external action for the next MFF 2014-20 and the reactions of both European Parliament (EP) and the Member States themselves. Finally, it attempts to answer the following questions: (1) what are the players’ main priorities and the possible conflicts between them?; and (2) will the MFF 2014-20 contribute to bridge the gap between ambitions, expectations and capabilities in Europe’s external relations?

By addressing these questions, the Paper underlines the fact that the negotiation of the MFF 2014-20 not only concerns the budget but also the policies that will determine the role of EU institutions and national governments in the decision-making process.

Challenges and Deficits in the EU’s External Action

Over the past decade the world has changed rapidly and the present economic crisis underlines even more the need for Europe to have stronger relations with a growing number of partners who are having an increasing impact on its financial and economic prospects. The relative weight in multilateral relations of emerging powers like Brazil, India and China is also on the rise. Furthermore, scarce natural resources, a rapidly expanding world population, threats associated with climate change, human security or conflicts in neighbouring countries are challenges which directly affect the EU and which can only be addressed in close cooperation with partner regions.

However, the EU has also changed. The Europe 2020 Strategy has a clear external projection and includes climate change and renewable energy among its objectives. Moreover, the Lisbon Treaty clearly defines common principles and objectives for the EU’s external action, contains provisions on its relations with neighbouring countries and tries to boost the international tools it has available as a global actor (Howorth, 2007). Nevertheless, the outcome of Europe’s Foreign Policy has been discouraging: from the crises in Libya and Syria to the problems of agreeing on the European Defence Agency (EDA) budget and from the continuing lack of capabilities to the role played individually by some Member States. Instead of promoting the EU’s character as an active and strong international actor, there has been the apparent decline of an international security actor in the making. The reason for these poor results is to be found around a group of variables, including the lack of institutional, economic, political and strategic resources.

The EU’s external action shortfalls become even more important in a context where the Union has no clear position in the international arena. The point of reference for defining the EU’s international role, the US, has dramatically changed, and the Union finds itself disoriented, bewildered and unable to take a position in the axis of world power and within the field of global dominance, be it in a ‘Greater Middle East’, the Pacific area or others. So far, the US had provided security to Europe and given stability to the global economic system, the basis for the EU’s economic development. This now appears to be over, and the EU has to provide its own security and economic growth. Because the EU lacks clear global goals regarding its own international role and Member States are reluctant to support a common Foreign Policy, it has lost credibility and attractiveness. Moreover, because of the euro crisis the EU has lost its reputation as a model for enlightened regional integration (Emerson, 2012), while the reluctance of Member States to take positions on international issues of little concern to them makes the EU appear as a dubious partner, especially when hard security is involved.

Another shortfall relates to weak institutional leadership. According to the Lisbon Treaty, the European External Action Service (EEAS) is to take over existing military and civilian-military bodies. The EEAS is supposed to coordinate all EU activities in foreign and security-defence policies, better serving the institutions involved in external relations and providing continuity in relations with non-EU countries. However, a year after the Service’s launching, structural problems persist. If under Solana’s leadership the EU engaged in its first –more than 20– military and civilian operations, since the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty and the appointment of the new High Representative its activity has been considerably reduced. Even if the EEAS is not working as expected, it is up to the 27 EU governments, not the EEAS itself, to reinvigorate the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP). However, certain EU Member States persistently refuse to provide the High Representative and the Service the very responsibilities assigned to them in the treaties. Member States criticise the administrative costs but seem to ‘forget’ that savings in the EU budget will not necessarily lead to a fall in their public expenditure and that the EEAS has the potential to generate an overall saving in public expenditure and to aid budgetary consolidation at the European level (Núñez Ferrer, 2012). One of the main challenges faced by the EEAS is to formulate a vision of how the EU should conduct is foreign policy with a comprehensive strategy and ensure that European institutions and Member States are prepared to back it up with all necessary resources (including finance).

As regards the lack of resources, the economic and financial crisis has underlined and intensified the shortfalls for the EU’s external action. A key problem today is that Europe’s ability to deliver effective military or civilian capabilities is at risk of erosion from the budget cuts. Hence, the need to continue to set up effective cooperation programmes is evident. Also, a continuous review of the level of ambition based on the European Security Strategy and the EU 2020 Strategy will be indispensable in the years to come (Kolin, 2009). Not least because of the financial crisis, Member States continue to be reluctant to work within the European Defence Agency(EDA) framework, some of them even refusing to accept any increase in the Agency’s budget.

The EU’s external action is also hindered by its economic weakness, due to the cuts in national defence budgets. In the context of budgetary austerity and the demands from Brussels to reduce public deficits, the budgets for national defence and foreign affairs continue to decrease. Furthermore, the effects of the crisis on national defence industries are giving rise to security risks: (1) operational capabilities deteriorate owing to lower technological demand and cost savings; (2) the development of dual technologies is impaired due to the lack of research in military applications; and (3) the industrial networks on which the major contractors depend will shrink, leading to lower income and employment (Fonfría Mesa, 2011).

The European Commission’s Proposal: A Budget for Europe 2020

On 29 June 2011 the European Commission presented ‘A Budget for Europe 2020’,[1] which also contained proposals on how the EU budget could help increase and foster the EU’s role in the world.[2] Despite the sovereign debt crisis and in order to close the gap between ambitions, expectations and capabilities, the Commission proposed increasing the overall budget for heading 4 from €55.9 billion to €70 billion. The total amount proposed for the external action heading, together with the European Development Fund (EDF), is €96.2 billion over the period 2014-20.

Contrary to previous demands, the Commission proposed not to include the EDF in the EU budget and the Fund will continue to be covered by the Member States on the basis of financial payments related to specific contribution shares. It is easy to conclude that the decision was taken in order to maintain the overall budget close to the demands of the net contributors. And, in fact, several Member States criticised this method because they perceived it as an underhand way of increasing the total budget.

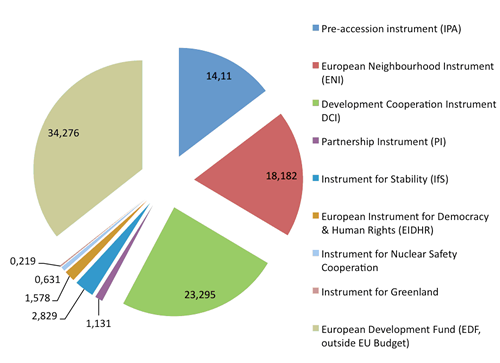

With regard to the proposal’s content, the Commission plans to focus on four policy priorities –enlargement, neighbourhood, cooperation with strategic partners and development cooperation–[3]with nine geographic and thematic instruments.

In global terms, the main instruments for cooperation with partner countries are: (1) the Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA); (2) the European Neighbourhood Instrument(ENI); (3) the Development Cooperation Instrument (DCI); (4) the Partnership Instrument(PI); and (5) the 11th European Development Fund (EDF).

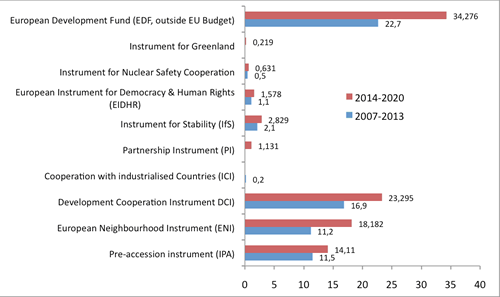

The Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA)[4] is, since 2007, the Enlargement Strategy’s financial pillar. The EU is currently dealing with four candidate countries and four potential candidates.[5] According to the proposals, during the MFF 2014-20 a greater emphasis will be placed on supporting reforms aimed at strengthening democratic institutions and the rule of law, as well as on implementing the EU 2020 objectives in the (potential) candidate countries. Moreover, the coherence between financial support and the overall progress made in the implementation of the pre-accession strategy will be increased. The proposed budget for the new IPA is €14.1 billion, an 18% increase compared with the current IPA (2007-13) of € 11.5 billion. In a first evaluation of the proposal, the EP insisted that the progress of the enlargement countries should be measured with better performance indicators and emphasised that issues such as refugees, inclusive economic and social development, and the importance of increasing local ownership should be especially addressed. According to the EP, well-performing countries should benefit from a performance reserve of 5% of the overall funding allocations.

The European Neighbourhood Instrument(ENI)[6] supports 16 partner countries to the East and South of the EU’s borders[7] and aims to help them achieve a closer economic integration with the EU and foster their transition to democracy. The ENI especially contributes to the Eastern Partnership and the Partnership for Democracy and Shared Prosperity with the Southern Mediterranean, as well as the Union for the Mediterranean. The ENI also supports the implementation of regional cooperation, for instance in the framework of the Northern Dimension and the Black Sea Synergy, as well as the external aspects of macro-regional strategies. In this framework, €18.2 billion are allocated for the ENI, 40% more than the amount available under the current period (2007-13). The significant increase reflects the ENP’s increased priority in the EU’s overall foreign policy. In addition, cooperation with the EU’s neighbours will be based on the ‘more for more’ principle (third countries that do more for democracy and human rights will receive more EU financial support).[8] The EP already asked for clearer assessments of neighbourhood countries’ progress with reforms in the annual country reports and to allow the revision of funding levels on that basis.

The Development Cooperation Instrument (DCI)[9] will primarily focus on combating poverty but will also contribute to the achievement of other objectives of the EU’s external action, in particular promoting democracy and good governance. In the same way as in the current period the DCI will be organised around geographical programmes to support bilateral and regional cooperation with developing countries as well as around thematic programmes. The Commission has also proposed to terminate its bilateral development aid schemes with 19 ‘wealthier countries’, such as Brazil, China, India and Argentina. The proposed budget for the new DCI is €23.3 billion, a 28% increase on the current DCI (2007-13).

Table 1. Indicative financial allocation for the period 2014-20 (€ million)

| Proposal | |

| Geographical programmes | 13,991.5 |

| Global public goods and challenges thematic programme | 6,303.2 |

| Of which: | |

| Environment and climate change (%) | 31.8 |

| Sustainable Energy (%) | 12.7 |

| Human development (%) | 20.0 |

| Food security and sustainable agriculture (%) | 28.4 |

| Migration and asylum (%) | 7.1 |

| Civil Society Organisations and Local Authorities thematic programme | 2,000 |

| Pan African programme | 1,000 |

| Total DCI | 23,295 |

Source: the authors, based on European Commission data.

Table 2. Financial allocation for the period 2007-13 (in € million)

| Allocation | |

| Geographical programmes | 10,060 (60%) |

| Of which: | |

| Latin America | 2.690 |

| Asia | 5.187 |

| Central Asia | 0.719 |

| Middle East | 0.481 |

| South Africa | 0.980 |

| Thematic and ad-hoc programmes | 5,596 (33%) |

| Of which: | |

| Investing in people | 1.060 |

| Environment and sustainable management of natural resources, including energy | 0.804 |

| Non-State actors and local authorities in development | 1.639 |

| Food security and sustainable agriculture | 1.709 |

| Migration and asylum | 0.384 |

| ACP Sugar Protocol countries | 1,240 (7%) |

| Total DCI | 16,900 |

Source: the authors, based on European Commission data.

The EP considers that development aid should not fall victim to the current climate of austerity, as it would be counter-productive for reaching the millennium development goals. In addition, MEPs argue that the quality of EU aid is recognised by the OECD. In this context, MEPs insist on the need for additional financing of aid for climate action in developing countries.

The Partnership Instrument(PI)[10] is the major innovation of the new 2014-20 external instruments package. It replaces the Industrialised Countries Instrument and will allow the EU to cooperate with emerging economies on issues related to core EU interests (Europe 2020 strategy) and on challenges of global concern. In accordance with the EC’s proposals, the PI will be a very flexible instrument. There will be no ex ante earmarking of funds and no classification of expenditure as Development Aid. The EP would like to open the instrument to all countries in which the EU has a significant interest but also underlines the need for a thorough re-evaluation of existing ‘strategic partnerships’.

The 11th European Development Fund (EDF) will remain outside the EU budget; however, its negotiation takes place in parallel with the MFF 2014-20. As in previous periods, the EDF will continue to cover cooperation with African, Caribbean and Pacific Countries (ACPs) as well as Overseas Countries and Territories (OCTs). The proposed budget for the EDF is €34.3 billion, a 33% increase on the current EDF. Only minor modifications are proposed compared with the 10th EDF (2008-13). In this respect, the EC recommends aligning Member States’ contributions to the EDF with the keys used for the EU budget. Furthermore, the EDF should integrate elements to ensure more flexibility and a fast reaction in case of unexpected events. The EP demanded the budgetisation of the EDF, although this should not lead to an overall reduction in development spending. According to the EP, a stronger scrutiny over the EDF would bring more democratic legitimacy and coherence to the EU’s policy with ACP Countries.

The main thematic instruments are: (1) the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR); and (2) the Instrument for Stability (IfS).

The European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR)[11] will provide support for the development of civil societies. Also in this context, the EC proposed enhancing the flexibility of the instrument in order to react promptly to human rights emergencies. The proposed budget for the EIDHR is €1.6 billion, a 31% increase. According to the EP, the EIDHR should only be a complementary instrument, to be used where no other instrument can be applied. Furthermore, the EP also required a greater flexibility to deal with urgent cases and to increase its independence from the consent of third countries’ authorities.

The Instrument for Stability (IfS)[12] is a horizontal instrument that has a global coverage which will address crisis situations, including natural disasters but also capacity-building for crisis preparedness and trans-regional threats (eg, terrorism and organised crime). The IfS was created in 2006 in recognition of the fact that due to administrative restrictions the EU could not respond to crises rapidly, despite having a Rapid Reaction Mechanism. The proposed budget for the new IfS is a 25% increase on the current period (2007-13). The IfS is an exceptional instrument to which recourse should only be made in the event that an adequate and effective response cannot be provided under other instruments.

Graph 1. Financial instruments for the EU’s external action and amounts proposed (in € million)

Source: the authors, based on European Commission data.

Graph 2. Financial instruments for the EU’s external action in the MFF 2007-2013 and amounts proposed in the MFF 2014-20 (in € million)

Source: the authors, based on European Commission data.

Although the Commission’s proposals retain substantially the same structure as those in the current MFF, they also introduce important changes. First of all, the increased overall budget for the financial instruments can be considered an indication that the EU aims to fulfil its commitments as stated in the Treaty of Lisbon. The EU’s financial instruments have historically been hampered by a lack of flexibility. Because of this, the EC wants to enhance flexibility and efficiency in order to raise the EU’s capacity to respond to unforeseen events. The demand for a greater flexibility in the implementation of these instruments also indicates an increased self-awareness of the EU’s institutions as actors in external affairs that decide where and how to spend money. Further differences to the current framework are the policy principles underpinning the set of instruments: differentiation and concentration, as well as the renewed attempt to attain a greater simplification. According to the principle of differentiation, the EU will allocate a larger proportion of funds on the basis of country capabilities (good governance), commitments, performance, potential impact on the EU and the decision of which countries are most in need. According to the principle of concentration, the EC proposes to focus external spending to avoid the inefficiencies resulting from dispersion and fragmentation. The conditionality between these principles and the implementation of the instruments indicates a strong value-based approach for the EU’s external action in 2014-20 which is also supported by the EP.

In addition, the EC aims to enhance cooperation with the private sector and other international donors. In this context, it proposes to exploit synergies with innovative financial instruments developed for internal policies in order to leverage more private funds.

Contentious Issues

The euro-zone crisis and its impact on national budgets seem to provide an important stimulus to considering the EU’s external actions as an alternative to those of individual Member States. In general terms, Member States approved the structure of heading 4 and agreed to focus development aid on the poorest countries. Up until the current stage of the negotiation, no Member State has asked for a reduction of the overall ceiling of heading 4, contrary to other spending headings (CAP and Cohesion Policy), and several are even in favour of increased financial resources for heading 4.

Nevertheless, the conflict between the ‘Friends of Cohesion Policy’,[13] and the ‘Friends of Better Spending’[14] could also affect the future of the financial instruments for external action. While the first focus on the fact that the Commission’s overall proposal for MFF 2014-20 constitutes an absolute minimum, the second insist on the need to limit public spending (Kölling & Serrano Leal, 2012) In this situation, Member States seeking to keep specific spending categories (such as PAC or the Cohesion policy) at the same level as proposed by the EC would probably argue that the cuts be made elsewhere (such as in heading 4). Also, Member States who advocate reduction in the EU budget would accept cuts in heading 4 in order to reach a final agreement.

The proposals to differentiate and concentrate external spending have been welcomed by the Member States (Kilnes & Sherriff, 2012). Nevertheless, it is reasonable to expect a sharp discussion on the question of which specific regions/countries should receive financial support and on how the principles mentioned above will be put into practice and on the degree of flexibility that is possible. The first disagreements over the future neighbourhood policy have already been aired. Several Member States have said that the neighbourhood policy is one of their priorities for heading 4 expenditure.[15] Although all Member States underlined their solidarity with North Africa, some have expressed their fears that resources from the eastern neighbourhood policy could be diverted to the South. The Eastern Member States called for a greater emphasis on the neighbourhood policy. While some countries uphold the ‘more for more’ principle, others consider it also necessary to take into account the countries’ needs. The EU’s enlargement is also a priority for most Member States. Some Member States underlined that the focus on pre-accession and enlargement should be increased and that the enlargement policy should continue to be supported by a specific financial instrument.[16]

The EU Council’s conclusions of 14 May 2012 also support linking the Union’s financial instruments with the political conditions in recipient countries (Faust, Koch et al., 2012).

The EDF’s integration in the EU budgetis supported by several Member States as a means to increase the democratic scrutiny and efficiency of the EU’s development policy. However, according to the ‘Friends of Better Spending’ this should be conditional on keeping the same amount for EU development funding. In the same way, the European External Action Service should be included under heading 4 or be separated in heading 5.

A key priority for Member States is to respect the commitment to devote 0.7% of their GNI to official development assistance by 2015, thus making a decisive step towards achieving the Millennium Development Goals. Several countries have insisted that the EU should ensure that over the period 2014-20 at least 90% of its overall external aid be official development assistance. In this context, a number of Member States are concerned about the growth of non-development spending in heading 4. However, the British government has calledfor a greater share to be directed to priority areas such as external action, research and climate change.

The Spanish government argued that there should be an increase in funds for Latin America, and expressed concern over the fact that the new DCI will exclude bilateral agreements with 11 Latin American countries. It particularly defended that Colombia, Ecuador and Peru should also benefit in the period 2014-20 from the Development Cooperation Instrument. The Spanish Foreign Minister, Jose Manuel García-Margallo, said that although Peru, Colombia and Ecuador are upper-middle income countries, they are still very vulnerable.

An interesting insight on the dispute over the MFF 2014-20 is the negotiation of the EU budget for 2013, for which the Council wants to limit the Commission’s draft well below the 6.85% increase requested by the EC. Heading 4 takes the major cut in this debate: -€1.03 billion in payments compared with the Commission’s draft and -9.75% compared with the 2012 budget. Nevertheless, in October the EP will vote on its position and MEPs are expected to defend the increases proposed by the EC in particular for the EU’s external action.[17]

Conclusions

The ‘Arab Spring’ has shown that the EU not only lacks effective short- and medium term instruments to contribute to conflict resolution but also that Member States have different national interests and defence cultures. The Libya crisis showed that Europe must be strong enough to maintain the stability in its neighbourhood and to actively shape its regional and global milieu. To be able to do this the EU must break out of its narrow focus on crisis management and ad hoc structures to take on all the functions commonly associated with the EU’s external action and military instruments (Simón & Mattelaer, 2011); this implies being aware of and anticipating situations as well being prepared to use prevention and deterrence through a permanent and forward presence. To succeed the EU requires instruments permanently on standby, a permanent planning and operational infrastructure and readiness to use force when necessary.

After analysing the negotiations on the EU’s external action budget for 2014-20, it can be concluded that there is almost no demand for a reduction of the overall ceilings as proposed by the EC. A key priority for Member States, EC and EP is to respect the commitment to devote 0.7% of GNI to official development assistance by 2015. Enlargement and the ENP are further priorities. While in the past Member States were reluctant to increase resources for the EU and to support a common Foreign Policy, there seems to be a consensus that the Union should have adequate financial resources in order to exploit the comparative advantage provided by its wide-ranging expertise, its role as a coordination facilitator and the possibility of exploiting economies of scale. In this respect, the EU and its Member States are also in agreement on improving the coherence and complementariness of their external policies. With regard to the financial instruments, there is an increased self-awareness of the EU’s institutions as actors in the Union’s external affairs that require a greater flexibility not only to react quickly in the event of emergency situations but also to better implement its instruments. However, taking into account the amount of the proposed budget for external action and the reluctance among Member States to offer more flexibility, it seems to be clear that the MFF 2014-20 will not solve the challenges mentioned above. Although the proposed increase in the EU budget could be considered a step in the right direction, the proposed overall amount of €96.2 billion seems to be insufficient to reach the objective of the EU 2020 Strategy to increase the Union’s role in the world. The proposals for the MFF 2014-20 are merely an evolution and not a revolution in the financial instruments available for the EU’s external action and the gap between ambitions, expectations and capabilities will not be closed with them. In order to do so, the EU would also have to address the institutional and structural shortfalls of its external action:

- The EU must also ensure that its other policies (agriculture, trade, environment and health) contribute rather than undermine the objectives of its external action (eg, poverty reduction and development objectives). Although the EC proposes an increase in the EU budget for development funding it still seems insufficient to ensure the fulfilment of its commitment to poverty eradication and to achieving the Millennium Development Goals.

- On the political level the EU’s institutions –eg, the High Representative and the EP– should have a stronger say in controlling and deciding when and how the EU’s external instruments are used. The financial instruments for external action continue to lack a political evaluation. It makes no sense to increase the total amount if the goals (as seen with the ‘Arab Spring’) it aims to fulfil are defeated.

- Because of national austerity budgets, the EU must –more than ever before– seek to focus its resources on where they are most needed, where they can have the greatest impact and where greater economies of scale can be achieved. In fact, given the lack of a permanent capability development mechanism, the EU’s Defence Ministers agreed at the end of 2010 on the softer concept of ‘pooling and sharing’ (Fernández Sola, 2011a, 2011b; Biscop & Coelmont, 2011). A clear need to pool and share scarce resources is essential to avoid duplication and maximise resources as national military and foreign affairs budgets are squeezed ever tighter by Europe’s deficit crisis.[18]

- In addition, the EU budget’s financial instruments are mainly focused on the former ‘first pillar’. The Community budget does not cover costs with military implications, which are entirely outside the EU budget and divided up between the Member States based on a GDP index set for each one. This split in the financing structure could reduce the coordination between the specific instruments, generate inconsistencies in external action, reduce the flexibility of the instruments themselves and diminish decision-making transparency.

- Finally, the functioning of the EDA should be improved. It should provide a solution to the dispersion and duplications in R&D projects as well as to the fragmentation of the defence markets and so create a competitive European defence equipment market and strengthen the Europe’s technological and industrial defence base.

Mario Kölling

García Pelayo Fellow, Centre of Political and Constitutional Studies, Madrid

Natividad Fernández Sola

National Research University-Higher School of Economics, Moscow

References

Biscop, S., & J. Coelmont (2011), ‘Pooling & Sharing: From Slow March to Quick March?’, Egmont Security Policy Brief, nr 23, Royal Institute of International Relations, Brussels, May.

Emerson, Michael (2012), ‘Implications of the Euro-zone Crisis for EU Foreign Policy: Costs and Opportunities’, CEPS Commentaries.

Faust, Jörg, & Svea Koch et al. (2012), ‘The Future of EU Budget Support: Political Conditions, Differentiation and Coordination’, European Think-Tanks Group in collaboration with the Institute of Development Policy and Management, University of Antwerp.

Fernández Sola, N. (2011a), ‘Las misiones militares de la UE en el siglo XXI’, Documentos Atenea, Revista Atenea.

Fernández Sola, N. (2011b), ‘L’impact des réductions budgétaires en Europe sur les capacités militaires européennes de projection’, Défense & Stratégie, nr 31, 20, 52-60.

Howorth, Jolyon (2009), ‘The Case for an EU Grand Strategy’, in Biscop et al., Europe: A Time for Strategy, Egmont Paper nr 27, Egmont, Brussels, 2009.

Fonfría Mesa, A. (2011), ‘Evolution of the Economic Crisis and its Influence on Security, Panorama Estratégico 2011, Instituto Español de Estudios Estratégicos, p. 39-64.

Kilnes, Ulrika, & Andrew Sherriff (2012), ‘Member States’ Positions on the Proposed 2014-20 EU Budget, An Analysis of the Statements Made at the 26th of March General Affairs Council Meeting with Particular Reference to External Action and the EDF’, ECDPM Briefing Note nr 37.

Kolin, V. (2009), ‘The European Defence Agency, not a Pandora’s Box but a Grand Experiment of Goodwill’, Obrana a strategie, 1/2009.

Kölling, Mario, & Cristina Serrano Leal (2012), ‘The Multiannual Financial Framework 2014-20: Spain at the Crossroads – The Spanish Balancing Act Between being a Net Contributor or a Net Beneficiary of the EU Budget’, ARI nr 50/2012, Real Instituto Elcano.

Núñez Ferrer, Jorge (2012), ‘Between a Rock and the Multiannual Financial Framework’, CEPS Commentary, 27/IV/2012.

Simón, L., & A. Mattelaer (2011), ‘EU Unity of Command: Planning and Conduct of CSDP Operations’, Egmont Paper, nr 41, Royal Institute of International Relations, Brussels, January.

[1] COM(2011) 500/I final, Brussels, 29/VI/2011.

[2] COM(2011) 865 final, Brussels, 7/XII/2011.

[3] COM(2011) 865 final, Brussels, 7/XII/2011.

[4] COM(2011) 838 final, Brussels, 7/XII/2011.

[5] Albania, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Iceland, Montenegro, Serbia, Turkey and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia.

[6] COM(2011) 839 final, Brussels, 7/XII/2011.

[7] Algeria, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Egypt, Georgia, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, the Republic of Moldova, Morocco, the occupied Palestinian territory, Syria, Tunisia and Ukraine.

[8] COM(2011) 303 Brussels, 25/V/2011.

[9] COM(2011) 840 Brussels, 7/XII/2011.

[10] COM(2011) 843 final, Brussels, 7/XII/2011.

[11] COM(2011) 844 final, Brussels, 7/XII/2011.

[12] COM(2011) 845 final, Brussels, 7/XII/2011.

[13] The signatories of the ‘Friends of Cohesion’ statements are Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Romania, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia and Spain.

[14] The signatories of the ‘Friends of Better Spending’ Non-paper are Austria, Germany, Finland, France, Italy, the Netherlands and Sweden.

[15] Bulgaria, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Hungary, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania and Slovakia.

[16] The European Council has granted the status of candidate country to Iceland, Montenegro, the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Turkey and Serbia. It has confirmed the European perspective of the Western Balkans.

[17]In the context of budgetary austerity and the requirements from Brussels to reduce public deficits, national defence budgets continue decreasing. This promotes the idea of Pooling and Sharing (P&S) capabilities as a way of optimising scarce economic resources.

‘2013 EU Budget’, Europolitics, 12/VII/2012.

[18] The December 2011 Council meeting of Defence Ministers further agreed on 11 cooperation proposals out of more than 200 initial plans. With a few notable exceptions (such as the Visegrad Battlegroup in which Poland, Slovakia, Hungary and the Czech Republic participate), many of the proposed cooperative defence ventures have so far failed to move beyond the theoretical. There was US pressure on Europe to halt its military decline, regardless of whether through the EU, bilaterally or through NATO.