Edited by: Bernhard Bartsch, Claudia Wessling.

Peer reviews by: Una Aleksandra Bērziņa-Čerenkova, Lucas Erlbacher, Miguel Otero-Iglesias, John Seaman.

Read also: Spain’s informal China policy: a coherent and Europeanist approach.

Executive summary

In this report, we take stock of national approaches to China across EU members states and important countries such as the United Kingdom, Norway and Switzerland. Experts from 24 countries have contributed their analysis, and the MERICS office in Brussels provided a chapter outlining current EU policies vis-à-vis China. Authors focused on the following guiding questions:

- National China strategies: Where do member states and other European countries stand?

- Mechanisms: How do European countries coordinate and share information on China?

- EU tools: Which national instruments exist for implementation?

- Risk analysis: Which approaches do countries take?

- Working with China: In which Chinese institutional frameworks do countries participate?

- Spotlight on Taiwan: What activities exist in this contested space?

European approaches to China vary considerably

The year 2023 has brought new momentum to the relationship between Europe and China. After more than three years of pandemic-related stagnation, mutual visits have picked up again. European heads of state and government and EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen traveled to Beijing; China’s new premier Li Qiang visited Germany and France in his first overseas trip since taking office. Despite the revival of contacts, numerous factors continue to burden relations between China and the EU, and other European countries.

The year 2023 has brought new momentum to the relationship between Europe and China.

Under Xi Jinping, China has changed and become more centralized, authoritarian and assertive abroad, and its goals are often in contradiction with European interests and values. Back in 2019, the EU Commission acknowledged this shift by introducing the tripartite definition of China as a partner for cooperation and negotiation, an economic competitor, and a systemic rival.

Since then, Xi and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) have continued their path: China has become more confrontational in the Taiwan Strait, more repressive in Xinjiang, tightened control over Hong Kong and promoted visions of an alternative international order. Increasing geopolitical and economic tensions between China and the United States have put pressure on the European Union to position itself in a complex triangle. The apparent “no limits” friendship with Russia, irrespective of Moscow’s war against Ukraine, has changed many European countries’ formerly favorable views of China, particularly in central and eastern Europe.

On the EU level, a range of mechanisms have been created to counter the increasingly geopolitical nature of Chinese influence and competitive distortions of markets, industries and technologies. These include investment screening, an anti-coercion instrument, an international procurement instrument (IPI), the Global Gateway Initiative and a planned law package aimed at monitoring and combatting foreign interference (including from China), as well as industrial policy initiatives such as the EU Chips Act.

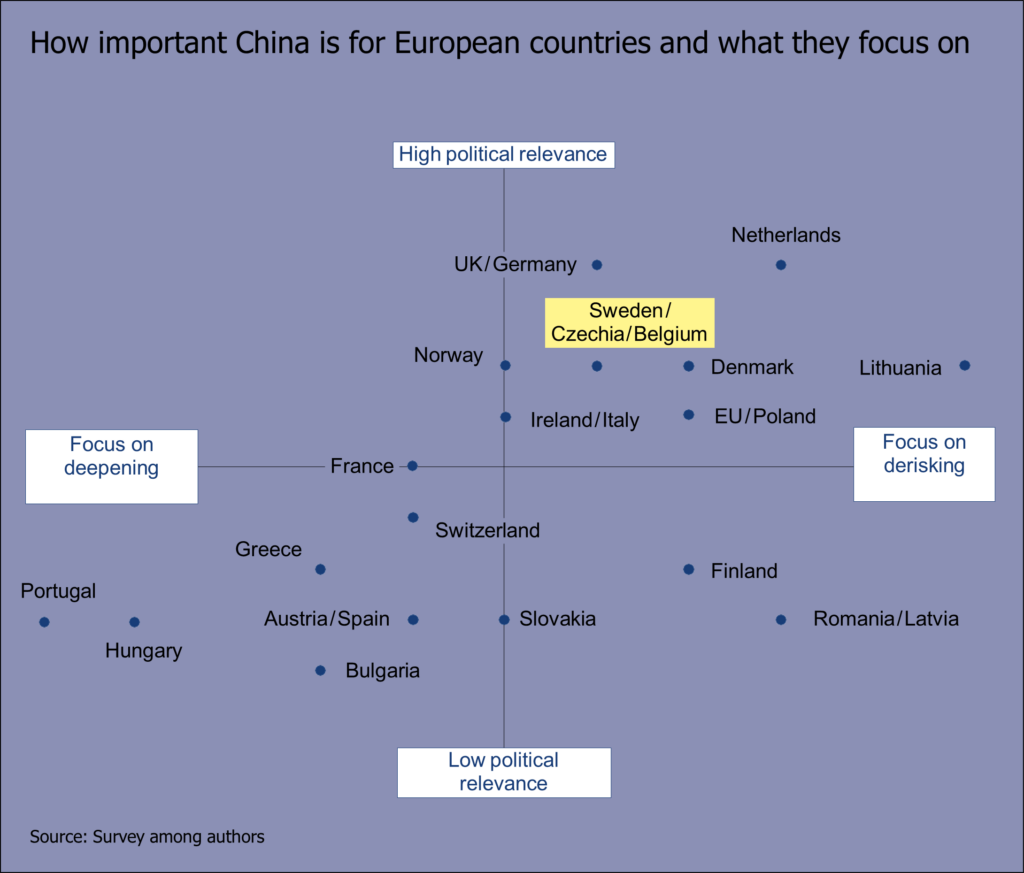

Exhibit 1. How important China is for European countries and what they focus on

Commission President Ursula von der Leyen introduced a “de-risking” proposal in March 2023 for navigating dependency risks in relations with China. The concept was also mentioned in the European Council conclusions on China after the June summit. Clearly, there has yet to be full agreement in the EU on how to operationalize “de-risking”, a sign that a unified European approach to China is still a long way off, even if there is more agreement today that some sort of strategic thinking on the issue is needed.

European approaches to China – whether by the EU, its member states and other countries in the region – have changed since the publication of the first ETNC report on “Mapping Europe-China Relations – A Bottom-up Approach” in 2015. The European Think-tank Network on China (ETNC) has for many years now analyzed the variations among European countries’ relations with China on a range of issues, including economic interdependencies, soft power, the Covid-19 pandemic, political values or the impact of China’s growing rivalry with the United States (all publications available on the network’s website: https://etnc.info). The EU institutions can only act with support of member states; at the same time, initiatives launched by Brussels often set the tone and pace for actions taken in European capitals.

Ten years after Xi Jinping took the helm in China, European countries have become more aligned on how to deal with this aspiring world power. However, approaches towards China vary depending on the intensity of relations, the extent and nature of economic dependence as well as attitudes towards the authoritarian government in China. Some have devised national China strategies, some prefer a less public, more decentralized approach, others do not consider China an important issue for their national politics. National approaches and their evolution in recent years are laid out in the country chapters of this report.

In addition to the chapters, each author completed a survey on the aforementioned guiding questions. Some questions were non-exclusive with multiple responses possible. For example, a country could have both an official, as well as a sectoral China strategy. Furthermore, respondents could choose to skip any question. As a result of this methodological approach, the number of responses may not match the total number of participants for each section of the survey.

Moreover, some of the questions were open-ended with some room for interpretation, such as what counts as an “unofficial” China strategy. Respondents could also indicate if they did not have enough knowledge or information to answer a specific question. Hence, the lack of a response does not necessarily imply the lack of a national mechanism or approach. The following is a summary of the key findings.

Almost all European countries have developed strategic approaches to China

Compared to the situation a decade ago, it can be clearly stated that the discussions on China in all European countries have matured. Many governments and other stakeholders have developed more sophisticated policies, coordination mechanisms and regulatory tools with which to approach China. Out of the 24 countries in this report, 20 countries and the European Union pursue more strategic approaches to China in the sense that they discuss, analyze and communicate their stances in structured and formalized settings.

Discussions on China in all European countries have mature.

Only a minority of European countries has published an official China strategy

Even though exchanges with China have intensified tremendously since the turn of the century, only six European countries reviewed in this report have cast their approach into a more formalized China strategy. Norway came in first in 2007, the Netherlands followed in 2013 and 2019. Sweden also joined the group in 2019, the same year the EU presented its tripartite “partner, competitor, rival” approach in its Strategic Outlook. Sweden, at the time, did not speak of a strategy, but a “communication”, stressing that it was following the EU’s example. Both governments published the strategies on request of their respective parliaments.

In 2021, Finland’s “Action Plan on China” painted a rather dire picture of the future of mutual relations. In July 2023, Germany published its first ever China strategy after fierce discussions within the ruling coalition over its general direction and tone. Outside the EU, Switzerland’s Federal Council, the country’s highest executive, published the “China Strategy 2021 – 2024”, calling out challenges more explicitly, while insisting on continued engagement.

Experiences with formulating national China strategies have been mixed. On the flipside were diplomatic pushback from the Chinese side and constant pressure to update strategies in a geopolitical environment that is continuously, and sometimes dramatically changing. There are good reasons for deciding against a full-fledged strategy, but it appears that many governments now see the benefits and the necessity of formalizing their approach to China on some level. On the positive side, authors in this report note gains on transparency, knowledge development and greater alignment from discussing the issue among wide groups of stakeholders.

A larger proportion of European countries has China-specific approaches embedded in their policy frameworks

Among the countries analyzed in this study, nine have relevant frameworks in place or formulated approaches in differing contexts that are recognized by the respective governments. But these are not published as official China strategies. The United Kingdom and Ireland, for instance, outlined their China policies in speeches given by their respective Foreign Ministers in spring 2023. The Belgian Foreign Ministry has developed a China strategy this year but has not yet publicly communicated on it. The Austrian government has announced the development of a China strategy, but with no time frame given and it remains unclear if it will ever come to fruition.

Political parties are only beginning to include China as a topic in their programs.

Others make China policies part of more overarching strategies. In France, China features as a topic in the Indo-Pacific Strategy. In Lithuania, it is part of the National Security Strategy and the Indo-Pacific Strategy published in 2021 and 2023 respectively. Latvia includes China policies in the yearly report of the Foreign Minister to parliament. In Spain it is mentioned in its more recent foreign policy and national security strategies. Denmark’s most recent foreign policy and security strategy (from 2023) contains some overall strategic guidance for relations with China, and it specifically refers to the EU as a key coordinator in handling the challenges from Beijing.

Eight countries in our analysis included approaches to China in their sectoral strategies. In Norway, the topic features in various policy fields. In the Czech Republic, the export strategy serves as a backdrop for describing approaches to China, while Greece uses the Greece-China Tourism Action Plan for this purpose. According to a survey the editors of this study conducted among the contributing authors, to date, only Bulgaria, Hungary and Poland are still lacking more coordinated strategic approaches to China.

Developing strategies below the threshold of an all-of-government process is, for some countries, a reasonable way to formulate goals in their China policies without having to deal with the sometimes painful and diplomatically controversial process of devising a stand- alone document.

On the domestic level, political parties in the analyzed countries are only beginning to include China as a topic in their programs. Several parties in the Czech Republic, Germany, the Netherlands and Switzerland have published position papers on policies towards China; in Lithuania, the topic is mentioned in electoral programs. On the EU level, the center-right European People’s Party and the pro-European Renew group also have formulated their own China strategies.

Better mechanisms for coordination and information sharing on China

Within governments, the level of attention for China-related issues, coordination, steering, knowledge and mechanisms of information sharing differs considerably between the countries analyzed in this study. The European Union itself and 11 countries have inter-ministerial coordination mechanisms in place. Among them are the Dutch “Interdepartementaal China Beraad” (ICB) and the “Interdepartementaal Directeurenoverleg China”, the Swedish “China Network of the Government Offices”, the Finnish “Valtionhallinnon Kiinaverkosto”, Poland’s “Inter-Ministerial Team for the Coordination of Activities for the Development of the Strategic Partnership with China”, or Germany’s regular ministerial state secretary rounds. Eight countries have established official consultation mechanisms between government and business. For instance, in Germany, the Asia-Pacific Committee on German Business (APA) regularly convenes meetings on China, bringing together the Economics Ministry and representatives from five major business associations. In the United Kingdom, there are various bodies which engage business and government, such as the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) or the China Britain Business Council. The Czech Republic, Finland, Spain and Sweden also have business-government formats on China in place.

Coordination on China becomes more challenging if one wants to connect China knowledge on the national and subnational level, as our analysis shows. Only the Netherlands, Norway and Finland have coordination mechanisms for municipalities. Three countries – Belgium, the Netherlands, and Sweden – have established national China competence centers. Their organizational structures are different, but they all have similar purposes: improving understanding of China, bringing together existing knowledge and responding to demands from governments on different levels.

Coordination becomes more challenging if one wants to connect China knowledge on the national and subnational level.

EU member states apply defensive tools conceived by Brussels differently

The EU has, in recent years, launched and established several instruments and regulations that are (not only, but also) aimed at improving capabilities to deal with China’s increasing economic and geopolitical clout. Among these:

- International Procurement Instrument

- Anti-foreign Subsidy legislation

- Foreign Direct Investment Screening

- Anti-coercion Instrument (pending approval)

- Anti-forced Labor Instrument (under negotiation)

- Chips Act (pending approval)

- Critical Raw Materials Act (under negotiation)

- Economic Security Strategy

Taking the screening mechanism for foreign direct investment (FDI screening) as an example, among the countries analyzed in this report, 16 EU member states have made national provisions, and four countries are preparing for implementation. Outside of the EU, the United Kingdom, Norway and Switzerland are engaged in parallel processes. For the time being, Greece and Bulgaria are not yet planning the introduction of similar tools.

In the context of China’s growing strength and ambitions in science, technology and innovation, the EU put forward in 2021 a strategy on cooperation in research and innovation (“Strategic, open, and reciprocal”). It suggests measures to protect research security and integrity in member states. The EU and some member states have started developing tools to better protect their interests, but the process proves to be cumbersome. According to this analysis, only six countries covered in this report have established regulations or guide- lines for research institutions – Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, Switzerland and the United Kingdom. In 2022, the EU published a Staff Working Document on tackling foreign interference in research and innovation (R&I). Risk analysis: an approach in the making

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 and the resulting economic fallout for European countries dependent on energy supplies from Russia, the issue of dependence on China has been fiercely discussed in Europe (also covered in the 2022 ETNC report: https://etnc.info/reports). The Commission’s “de-risking” agenda and the June 2023 frame- work on a European Economic Security Strategy are aimed at minimizing risks arising from economic exchanges in geopolitically challenging times. However, only the EU itself, Finland and the Netherlands have presented systematic and public analyses of dependencies, e.g., in critical raw materials or supplies.

Two countries – Lithuania and Latvia – have compiled internal reports on the issue, four countries – the Czech Republic, Germany, Norway, and Poland – are working on assessments. Sweden and France have also conducted an analysis. Austria, Greece, and Slovakia, on the other hand, do not appear to plan any risk assessments. In Bulgaria, the war in Ukraine and the overarching risk stemming from chronic dependence on Russian energy imports and technology are hotly debated. However, this has not resulted in any substantial reviews or policy shifts. For ten countries, no information was available to the experts compiling this report.

European countries are increasingly wary of participating in Chinese frameworks

In the past decade, China has systematically established its own institutional frameworks to increase geopolitical and economic influence. One of these frameworks is the 16+1 initiative established in 2012 to engage with Central and Eastern European countries – a format that was sometimes criticized in the EU as undermining its unity.

After a period of expansion (Greece entered the format in 2019), the group is now down to “14+1”. Seven countries (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovakia) analyzed in this report are part of it, among them, two (Romania, Bulgaria) have downgraded their participation in the most recent summit meeting in 2021. Two others covered in this report (Latvia, Lithuania) have withdrawn from the group, while a third (Estonia) has also withdrawn. While some country representatives mentioned disappointment over China’s economic engagement in the region as their main motive for dropping out, others have grown wary of China’s support for Russia and coercive measures for deepening relations with Taiwan. The future of 14+1 is uncertain.

China has established its own institutional frameworks to increase geopolitical and economic influence.

The Belt and Road Initiative, launched by Xi Jinping in 2013, is the best-known among China’s initiatives to go global and create markets, investment opportunities for its companies but also increase political influence in the participating countries. Ten countries analyzed in this report have a high-level BRI agreement (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia). Switzerland and Austria entertain so- called “sectoral” agreements in the BRI context. In the case of Romania, an agreement was signed during the visit to China of a state secretary in the Ministry of Economy and Commerce back in 2015. Since the text is not public, it remains unclear whether it is a general or a sectoral one.

In Italy, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni announced during her election campaign an intention of leaving the agreement that Rome signed in 2019 and which will be automatically renewed next year. Now, her right-wing government seems caught between a rock and a hard place: on the one hand, there is fierce opposition to withdrawing in the local business community, which is worried about losing preferential treatment they perceive to enjoy as BRI members. On the other hand, a competing narrative in Italy attests that other countries get the same treatment without any MoU. On the international stage, the US and European partners expect Meloni to deliver on her campaign promise.

A majority of 19 countries participates in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), a multilateral development bank and financial institution to support social and economic development projects globally. The EU and five other countries covered in this report are not members (Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia).

Approaches to Taiwan: Nonissue for some, increasing contacts for others

While some of the countries analyzed follow China’s expectations and steer clear of entertaining even informal contacts with Taiwan, there is a trend among others for increased exchanges at the political level. In light of rising military tensions in the Taiwan Strait and calls from the Xi government for unification, the number of high-level exchanges between European and Taiwanese politicians has increased recently, with more than a dozen visits in 2022/23 so far.

| Most recent high-level visit to Taiwan from countries surveyed in this report 2023: Czech Republic: Markéta Pekarová Adamová, Speaker of the Chamber of Deputies of the Czech Parliament. France: Alain Richard, Vice-President of the Senate, Head of the Senate-Taiwan study and exchange group, former Minister of Defense (plus delegation). Germany: Bettina Stark-Watzinger, Minister of Education and Science. Ireland: Parliamentarians John McGuinness, Brendan Smith, Cathal Berry, and senators Seán Kyne, Martin Conway. Lithuania: Aušrinė Armonaitė, Minister of Economy and Innovation. Romania: Catalin Tenita, Member of Parliament (Chamber of Deputies). Spain: Rosa Romero Sánchez, Chair of the Health Commission – Congress of Deputies. Switzerland: Fabian Molina, National Councilor (Co-President Parliamentary Friendship Group Switzerland-Taiwan). 2022: Finland: Petri Peltonen, Under Secretary of State, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment. Netherlands: Sjoerd Sjoerdsma, Member of Parliament. Poland: Grzegorz Piechowiak, Deputy Minister of Economic Development and Technology. Slovakia: Peter Gerhart, Deputy Minister of Economy. Milan Laurenčík, Deputy Speaker of Parliament. Sweden: Håkan Jevrell, State Secretary to Minister for International Development Cooperation and Foreign Trade Johan Forssell. United Kingdom: Greg Hands, Trade Minister, Alicia Kearns, Chair, House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee (plus delegation). 2021: Latvia: Parliamentary delegation of Baltic states. Before 2020: Austria: Werner Amon, Parliamentarian, 2018. Bulgaria: Rumen Yonchev, Ventsislav Lakov, Petya Raeva, Vladimir Toshev, Members of Bulgaria’s National Assembly (private trip paid by Taiwan), 2014. Denmark: Pia Kjærsgaard, Member of parliament, 2019. Italy: Interparliamentary Friendship Group, 2016. |

The road ahead for shaping future relations with China

In this report we observe the trend that some European governments are becoming more aligned because they perceive China as being more confrontational than ever. The fact that China policies in many European countries have shifted to become more critical also reflects the changes in the US approach to the People’s Republic, which has also become much more confrontational since 2017, when it first labeled Beijing as a “strategic competitor”.

Another trend worth mentioning is the apparent gap in a number of countries between the business community, on the one hand, who tends towards continued and even stronger engagement with China, and economy, foreign affairs or defense ministries and intelligence communities, on the other hand, who are more worried about critical dependencies and security issues.

Approaches vis-à-vis China depend on the intensity of mutual relations.

The approaches the countries analyzed in this study take vis-à-vis China depend on the intensity of mutual relations – and also on the political views of Beijing’s stances. In spite of the many differences, we argue that there is common ground that could possibly facilitate a more coordinated European approach to China in the future:

- In shaping relations with China, there is a great deal of agreement among contributors to this report that it is important to keep channels of communication open, to re-invigorate political exchange regardless of differences. The handling of cooperation formats such as BRI, 14+1 and others should be subjected to a critical examination in this context.

- In economic relations with China, the “de-risking” approach mainstreamed by EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen in March 2023 is lauded by some and contested by others. Countries need to strive for a balance between seeking opportunities, cutting dependencies and attracting investments that are beneficial. The defensive mechanisms launched by the EU, like the FDI screening mechanism and the anti-coercion instrument, are considered important tools for managing these relations.

- In the realm of security policies, countries need to face and tackle the challenges posed by China and find unified positions on crucial geopolitical issues like China’s support for Russia despite the brutal war in Ukraine, the pressure exerted on Taiwan or Beijing’s influencing strategies in foreign countries.

- On the EU level, capacity-building needs to be front and center to navigate relations successfully and jointly with China. This entails sharing analysis and information to devise strategies and finding language that member states can agree on and unite behind.

- Seeking alignment within the EU, but also with like-minded partners, is another prerequisite for successful implementation of a strategic approach to China. This also means finding consensus within the EU about how to manage relations with the United States, which is compounded by concerns voiced in some European capitals about transatlantic dependencies while others pivot closer to Washington. To defend its own interests in a global environment shaped by increasing competition between the Unit- ed States and China, the EU also needs to create maneuvering space by safeguarding its sovereignty.

What happened since …

… May 2023. That was when the articles for this ETNC report were finalized. On this page, we include updates of crucial events concerning China policies in some of the countries analyzed:

Bulgaria: On June 6th, a new government came into office, which seems set to toughen the stance on Russia. This may affect relations with China should the Sino-Russian friend- ship of “no limits” persevere. In July, the Bulgarian Diplomatic Institute to the Minister of Foreign Affairs initiated an expert consultation to help developing the first National Foreign Policy Strategy. This will likely include language on China, as the institute is currently building up in-house China expertise.

Czech Republic: A new Security Strategy was issued on June 28th. It explicitly mentions China as a security threat. Taiwan’s Foreign Minister Joseph Wu visited Prague for the second time in June 2023, meeting the Speakers of both parliament chambers.

Lithuania: An Indo-Pacific Strategy was published in early July, just before Vilnius hosted the NATO Summit. Despite its stated adherence to One China Policy, the assessment of Beijing remains one of alarm.

Netherlands: In May, the government opened a Contact Point for Economic Security aimed at businesses. In June, the investment screening law (VIFO) came into force, while in July, the Dutch coalition government collapsed, leading to the cancellation of a parliamentary visit to Taiwan.

Slovakia: At the end of May 2023, Slovakia’s Deputy Foreign Minister Ingrid Brocková traveled to Beijing on an official visit. During a meeting with her counterpart Deng Li, she raised several contentious issues, including China’s position on the Russian aggression against Ukraine, human rights in China, the status of Taiwan, as well as presence of an illegal Chinese police station in Slovakia. In June 2023, the third round of the Taiwanese-Slovak Commission on Economic Cooperation took place in Taipei, attended by Slovakia’s Deputy Minister of Economy Peter Švec. The gathering concluded by signing eight MoUs and one agreement to deepen partnerships in the fields of culture, economy and trade, academic exchanges, healthcare, and semiconductors.

Sweden: At the Stockholm China Forum in May 2023, Prime Minister Kristersson acknowledged “the need for de-risking”, which indicates that Sweden supports the EU Commission’s approach. He also stated that the US is “the most important security partner for Sweden and the EU”, emphasizing the importance of the transatlantic link.