The Spanish economy had a good year in 2015, but it ended with an inconclusive election on 20 December that produced a fragmented parliament. Almost two months later there is still no sign of a new government, and the potential impact on the economy’s recovery after a long recession is beginning to cause concern.

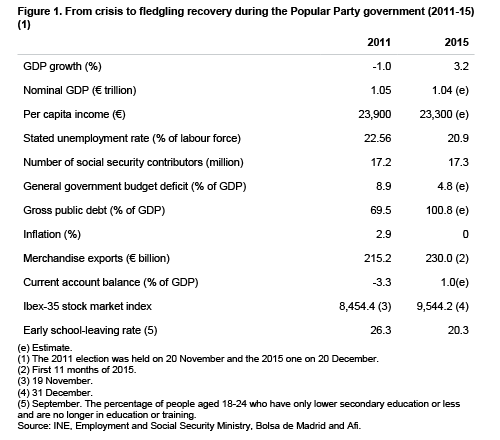

The economy grew 3.2% last year, the strongest growth since 2008. GDP, however, is still below the pre-crisis level. The stated number of unemployed fell by 678,200 to just below 4.8 million, but this sharp drop hardly dented the jobless rate, which is still more than 20%. Inflation was zero, a record 68.1 million tourists visited the country (3 million more than in 2014), exports were at an all-time high (€230 billion in the first 11 months), the current account was in surplus (around 1% of GDP) and banks’ earnings were much improved, following an EU bail-out of part of the financial system.

By any standards these are good results (see Figure 1). Other than comments such as those by Ana Patricia Botín, Executive Chairman of Santander, Spain’s largest bank, that the ‘telephone rings less than two months ago to buy assets’, and a rise in the risk premium there are few tangible signs of a fall out from the election. The premium on Spain’s 10-year government bonds –the difference between Spain’s yield and that of benchmark Germany’s– rose from 135 bp last week to 151 on 9 February, while the Ibex 35, the benchmark index of the Madrid stock exchange, dropped below 8,000, its lowest level since July 2013 and still way below its peak of more than 15,000 in 2007.

The outlook is clouded by some pressing issues that need to be tackled but no government within sight to do so. King Felipe VI entrusted the Socialists’ leader, Pedro Sánchez, on 3 February with the task of forming a new government, after Mariano Rajoy, the incumbent Popular Party (PP) Prime Minister, turned down the offer to start coalition talks. Rajoy said he saw no chance of winning sufficient support.

Both the PP and the Socialists, the two parties that have alternated in power since 1982, did very badly in the election: the PP won 123 of the 350 seats in parliament (down from 186) and the Socialists 90 (110), while the anti-austerity Podemos and the centrist Ciudadanos, campaigning nationally for the first time, got 69 and 40 seats, respectively, and broke the mould of post-Franco politics. Several other regional parties also won seats, further complicating the arithmetic for forming a stable government. Fresh elections could be called in May or June, but with little change in the results, according to all opinion polls.

Spain is one of the very few EU countries not to have had a coalition government in the last 40 years. And neither has the political class forged a culture of compromises and pacts, which the election results show is what Spaniards want, but which the political parties, stuck in megaphone diplomacy and ‘red lines’, have so far failed to deliver. That said, Belgium took 541 days to form a government (announced in 2011), and the economy did not collapse.

The European Commission fired a warning shot across Spain’s bows on 4 February when it said that ‘whatever the new government, it must make adjustments [to the budget] in 2016’. The PP controversially rushed through the 2016 budget last September, as it was crystal clear that no party would win the December election, and the government wanted the Commission’s approval before the polls. As it turned out, the budget fell short of the EU’s spending rules and the government was rebuked, but it rejected the request for stricter execution of the 2015 budget and cuts to ensure the 2016 budget was compliant. But at least there is a budget in place.

According to the Commission’s latest forecast, Spain’s budget shortfall was 4.8% of GDP in 2015, 0.6 pp above target, and this year’s deficit is projected at 3.6% of GDP –missing the 2.8% target and leaving the euro zone’s fourth-largest economy in breach of the bloc’s 3% deficit ceiling–. The Socialists want to postpone the 3% target until 2017, a proposal, should it happen, that would not go down well in Brussels.

Just as the incumbent government is not in a position to make changes to the budget so, too, it is powerless to do anything about the emerging social security crisis and the need to reform the Toledo Pact (first approved by parliament in 1995) to guarantee the system’s future.

The greying population and a low fertility rate, combined with the very high unemployment (the number of social-security contributors is still 2 million less than the peak in 2007), has pushed up the dependency ratio (the inactive elderly as a percentage of the working age population) and raised serious questions about the sustainability of the pay-as-you-go pension system.

In order to pay pensions, the government raided the reserve fund built up during the boom years, reducing it from a peak of €66.8 billion in 2011 to €32.4 billion at the end of 2015. If this pace of drawing down the reserve continues and no measures are taken, the reserve will run out in 2019.

Measures need to be taken well before then; the sooner there is a new government the better.

* The Elcano Royal Institute published the author’s new book, A New Course for Spain: Beyond the Crisis, this month.