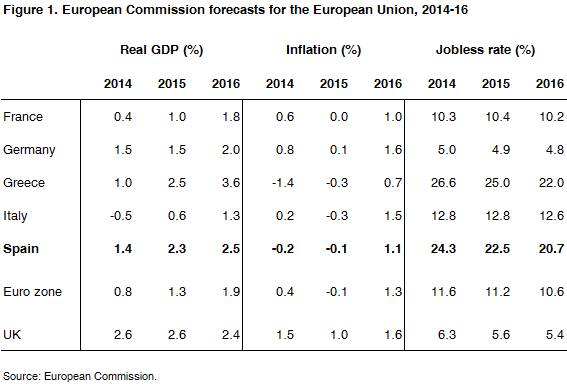

The Spanish economy is gaining momentum at a faster pace than expected, as evidenced by the constant upgrading of the GDP growth forecasts for the country by the International Monetary Fund and the European Commission.

This month the Commission put growth at 2.3% in 2015 and 2.5% in 2016, higher than the euro zone average (see Figure 1). The previous forecasts, made last autumn, were 1.7% and 2.2%, respectively. The research department of BBVA, Spain’s second-largest bank, puts growth even higher this year at 2.7%.

The IMF has been even slower to recognise Spain’s recovery: its upgrading last month to 2% growth this year from a previous 1.8% was the sixth consecutive improvement. Together with the US, Spain (the euro zone’s fourth-largest economy) was the only economy of significance whose growth forecast was not downgraded. A year ago, the IMF projected growth of just 0.8% for Spain.

These institutions, which always tend to err on the side of caution, do seem to have underestimated the incipient recovery in domestic demand, which after several years has replaced external demand (ie, exports) as the engine of GDP growth.

Domestic demand is forecast to contribute 2.6 percentage points to this year’s GDP growth, while net exports’ contribution will be 0.3 points negative (leaving overall growth at 2.3%). In 2013, when the economy was still in recession, domestic demand’s contribution was 2.7 points negative and net exports 1.4 points positive, leaving growth at -1.3%. Imports (+5.7%) grew faster than exports (+2.5%) in 2014 for the first time since 2006.

The upturn in domestic demand, traditionally the engine of growth in Spain, reflects the easier financing conditions resulting from the European Central Bank’s monetary policy interventions, greater investor confidence, labour market reforms and lower oil prices, all of which is spurring growth after three years of recession (which ended in the fourth quarter of 2013) and seven years of adjustments since the bursting of the massive property bubble in 2008.

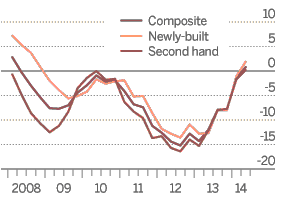

Two indicators, in particular, show the timid recovery in domestic consumption. Car sales rose 18.4% in 2014 to 855,308, the highest level since 2010 but still far from the average of 1.6 million between 2004 and 2008. Growth continued in January (+27.5% year-on-year, the highest rise for that month in 20 years). And property sales were slightly higher in 2014 (+2.2%) for the first time in four years, suggesting that the corner has finally been turned in the housing market, although most of the homes sold were second hand and not new. The number of housing starts plummeted from 750,000 in 2006 to an estimated 38,000 in 2014. House prices began to rise last year for the first time since 2008 (see Figure 2).

The tourism industry, a cornerstone of the Spanish economy (it generates more than 10% of GDP and a larger share of jobs), also enjoyed a record year in 2014 with around 65 million visitors (+7% and 18.4 million more than Spain’s population). Hotel prices have been held down and the 15 million British tourists benefited from the stronger pound.

The recovery is also no longer being held back so much by banks’ reluctance to lend, particularly to small and medium-sized companies (the backbone of corporate Spain), some of which were so starved of working capital that they went out of business.

Lending fell by close to 6% in 2014 (-1.5% across the whole euro zone), according to EY, the accountancy and consulting firm, which projects growth of 1.8% this year and 5.4% in 2016.

All but one Spanish bank, and a minor one at that, sailed through the European Central Bank’s stress tests last year. This followed the restructuring linked to a €41 billion bailout from the EU in 2012 of several banks, most notably Bankia, whose collapse threatened to bring down the whole financial system.

No bank needed to raise new capital after the exercise. In the case of Santander, the euro-zone’s largest bank by market capitalisation, it was one of the banks in the baseline scenario that generates the most capital in the three-year period and in the adverse scenario (plausible but most unlikely to occur), it is the bank with the least negative impact among the big banks.

The victory of the left-wing anti-establishment party Syriza in Greece’s general election last month has hardly affected Spain, although it has a similar party, Podemos, that is riding high in the polls and is forecast to win the general election due to be held by December.

Podemos, like Syriza, is pushing for an easing of austerity measures and debt relief. The comparisons between Greece and Spain are tenuous; the medicine that Spain has swallowed, bitter though it has been, is beginning to work. This has not been the case in Greece, whose much tougher medicine has kept the country in intensive care.

The risk premium on Spain’s 10-year government bonds over Germany’s equivalent, an indicator of international investor confidence, has risen since Syriza’s victory on 25 January by only 17 basis points to 1.17 percentage points, lower than Italy. Greece’s risk premium has increased from 9.10 to 9.69 percentage points.

Spain may be winning the war, but the battle is far from over. The unemployment rate has dropped from a peak of 26.9% at the end of 2013 but is still above 23%, despite the creation of more than 430,000 jobs (many of them precarious) in 2014. The pool of unemployed (5.4 million) is so big (almost two-thirds of whom have been without work for more than two years) that even with the economy growing at more than 2%, the jobless rate will remain above 20% until 2017. The workforce, however, is increasing and suggests that those without work who gave up hope of finding a job are looking for work again.

Thanks to the labour market reforms in 2012, the GDP growth threshold for job creation has been lowered.

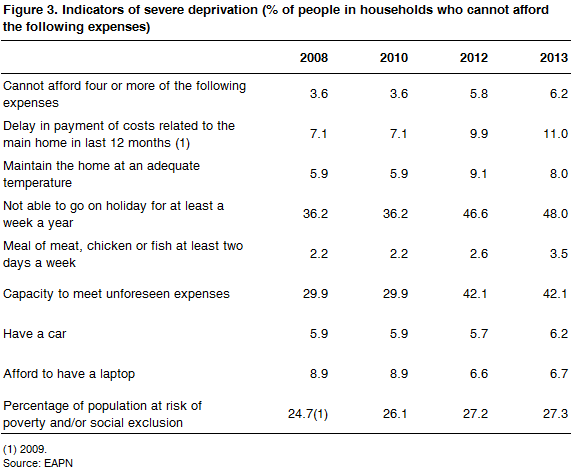

There is no doubt that Spain is firmly recovering, although it is yet to recover the pre-crisis GDP level, and the reality for many is harsh. The number of people at risk of poverty and/or social exclusion rose by 1.9 million between 2009 and 2013 (latest figure) to 12.86 million (27% of the population), according to the Spanish chapter of the European Anti Poverty Network (EAPN, see Figure 3).

Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy believes the recovery vindicates his policies, as does the fiscally-conservative Angela Merkel, Germany’s Chancellor, for whom Rajoy has become something of a poster boy. Only time will tell, but some analysts believe the gathering pace of the Spanish economy could see Rajoy’s Popular Party, contrary to what the opinion polls say today, very narrowly squeeze back into office after the next election.