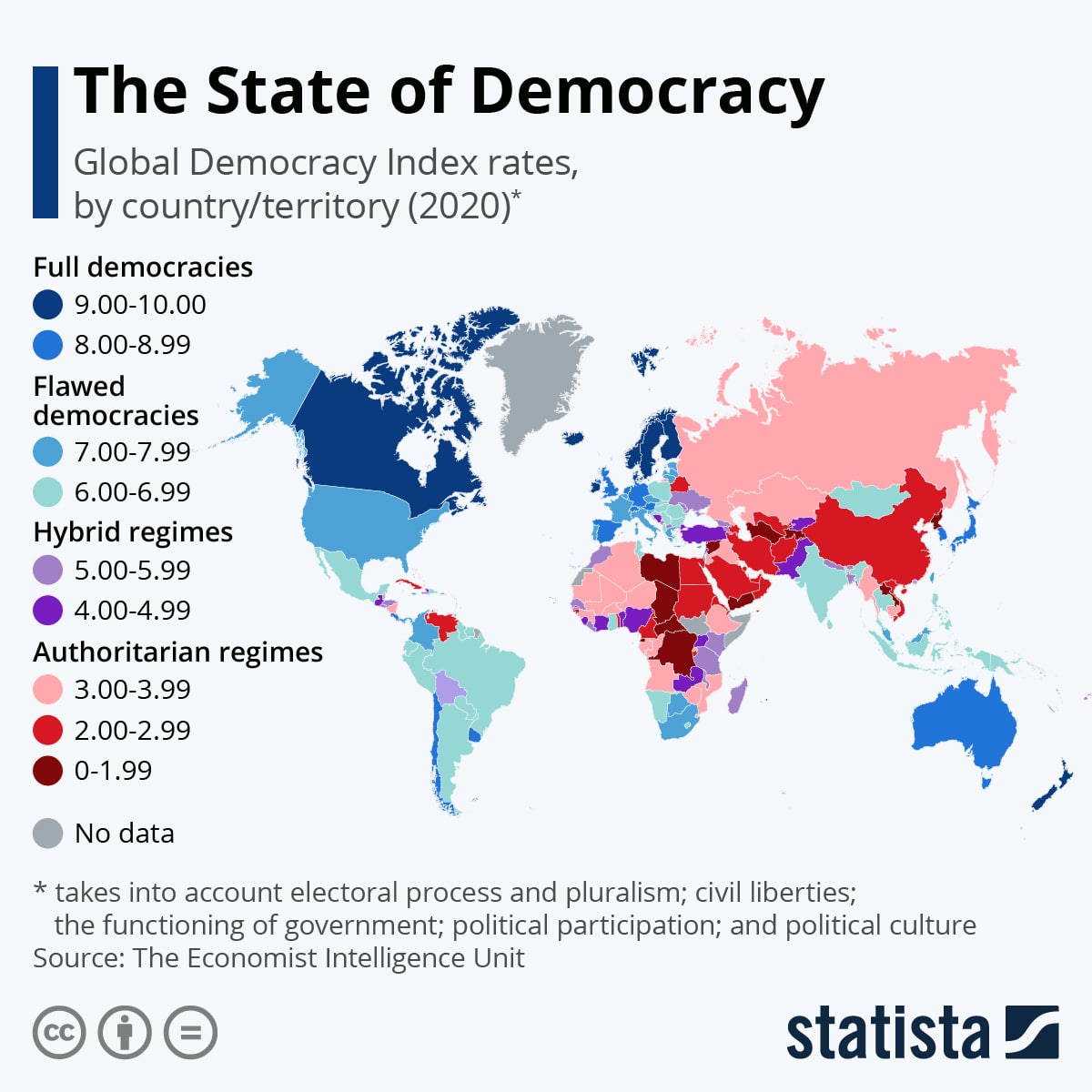

According to the latest edition of the Democracy Index by The Economist Intelligence Unit, globally there are more authoritarian and hybrid regimes than democratic countries: 91 States against 76. Within “democracy” category, 54 countries are flawed democracies, while only 22 States may be found at the “full democracy” label. Full democracies do not only represent the lowest figure in terms of number of countries –13.2%–, but it also makes up the lowest percentage of world’s population –5.7%. Furthermore, although flawed democracies host the largest world’s population group in the index –42.7%–, still authoritarian and hybrid regimes continue excelling the “democracies” group. The 51.6% of humanity live in States where, to a greater or lesser extent, free and fair elections are not guaranteed, there is no political pluralism, institutional instability –partial or total– occurs on a daily basis, the rule of law and the fight against corruption are weak frameworks, civil society remains fragile, press and expression freedoms are overthrown by censorship tools, and the judiciary is not independent.

However, this scenario is nothing new. Since the first report in 2006, average global score has always levelled up around 5.5 points –under the “hybrid regime” category, from 4.0 to 6.0 points. Nevertheless, this year’s edition distinguishes itself from the previous ones because it triggers a sense of urgency: 2019 has the worst average global score since its creation (5.44 points on a scale of 0 to 10). 2019 result is even lower than the 2010 record, which represent a sharp democratic quality’s decline driven by the global economic and financial crisis. The driving factor is given to downturn in Latin America –due to electoral fraud and corruption– and Sub-Saharan Africa –because of repression during street protests.

By contrast, what is happening goes beyond this statement: it is the inception of the second stage of the “democratic recession”, noted by Thomas Friedman in 2008. He spoke about the retreat of democracies due to the loss of influence over United States’ leadership and the emergence of new powers, which are now illustrated with the comeback of the great-power competition narrative. Herein, a decade later, we propose that the demos slowdown –in the case of democratic countries– is not only due to a crisis related to the reconfiguration of geopolitical forces, and its impact on diverse dimensions of multilateralism –trade, public diplomacy, or values. This is also due to the fact that democracies forget their raison d’être and their leitmotiv. Democracies have also forgotten to be ahead of transnational and global changes which affect them from a country-risk perspective. During these last years, global order has become a two-fold system: a structure in which, if agents wish to be part of, they must devote more efforts; while at the same time these agents –States- are over time losing their capacity because their own agency is questioned from within.

This is confirmed by the Democracy Index: the single variable which has risen, compared to 2008, is political participation –from 4.59 to 5.28. The definition of 2019 as the year of street protest and the recently mentioned “slowbalisation” –the global order has passed the peak of global integration, with a forthcoming recession or growth at a slower pace– are symptoms of the need for democracies to adapt the way they look at themselves and the near future, which is characterized by the lack of full control over seemingly exogenous events –such as climate change and digitalisation–, which instead are part of every State’s idiosyncrasy because States are held accountable for their genesis and responsiveness.

In such a way, which is the path for democracies to assume long-term uncertainty in a scenario where a mere country-risk matrix is no longer possible? The first mistake is to assume that concrete, future events may be foreseen. The second mistake is to believe that the future will look like the present. It almost never does. The key idea is not about knowing the concrete, but the trend. Hence, there is a need for experts specialised in coming future issues’ policy-making with a holistic mindset of the international world, so that they may complement each other to enhance democracy. In order to overcome blind spots and dead angles, public institutions can and have to implement risk analysis methodologies by which, knowing what is likely to occur –without exactly knowing when, where and how–, they may have contingency, quick response plans at their disposal.

To do so, intelligence techniques are highly useful when it comes down to prepare a country facing trends and sudden changes. These techniques are usually managed on a short-term tactical level. However, its redefinition towards a long-term, strategic mindset is an idea which must and, indeed, can be done. This methodology is used in the United States’ public policy making. It also serves as a conversation enabler among those sectors which, in other countries such as Spain, are conceived as disjointed spheres. The first step is to identify errors from the past: concretely, those which were avoidable and those which were not preventable. There are several options, although we will limit to refer to a few ones. The first method is to challenge a single, strongly held view or consensus by building the best possible case for an alternative scenario and potential evolutions of such an input (devil’s advocacy technique from the CIA). Another way is to highlight a seemingly unlikely event that would have major policy consequences if it happened: this is the high-impact/low-probability analysis, which makes some rarely unheard variables become “observables”. If we want to have preventing intervention protocol, a valuable technique is what-if analysis, which is already used by the Paris-based European Union Institute for Security Studies. It does not analyse consequences, but instead the causes of a possible scenario (involved stakeholders, regulations, sociological and economic factors). Additionally, alongside internal prevention and increasing response capabilities, red teaming is a highly useful analysis as it provides adversarial response to the organisation’s point of view, then helping the organisation to improve their problem-solving capabilities and overcome cultural bias.

These techniques –alongside too many others with more analytical deepening and framing, being diagnostic, contrarian or imaginative thinking techniques– show that whether a full democracy, such as Spain, vies for acquiring a strategic outlook, it has to respond to the near-term volatility, not only on an “island” basis –focused on the state–, but also putting the shift onto the “orbit” –spheres of influence– and “community” –in a global world, the local basis is even more important due to greater margin of manoeuvre by non-state actors and private groups.

Willingness and resources are essential assets when becoming a strategic-minded democracy which is ahead of events. The development, success and sustained efficiency of these efforts will rely on taking a leap forward in the gathering of new ways of communicating with other countries, as well as new specialisations –internally. In short, on the boldness of embracing decisive ideas and minds, with a logical and holistic mindset –such as the outside-in thinking technique– with the purpose of guaranteeing, in an uncertain world which no longer works from a country-risk perspective, the main goal: updated, recycled democracies, which are at the forefront of responsiveness towards problems and people.