The Spanish economy’s external sector has suffered the impact of COVID-19 with greater intensity than other EU countries. This is mainly due to its sector-based specialisation, though it should be noted that before the pandemic it was already showing a slight deceleration in both exports and imports.

There are many uncertainties looming over the Spanish economy, not least because of the uncertainties that exist as to the pandemic’s duration and control. The external sector has the potential to contribute to economic recovery. This requires, first, that it receives greater attention from both civil society and those responsible for economic policy.

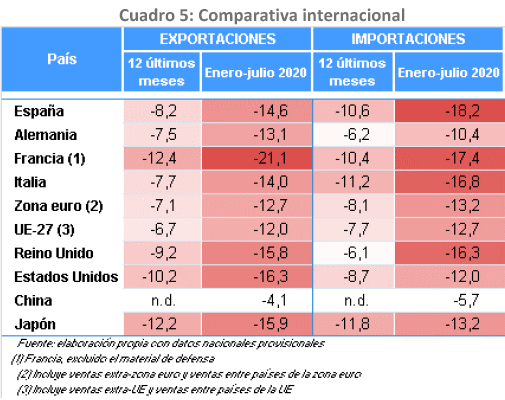

The latest statistics on the foreign goods trade for the period January-July 2020 show a 14.6% decrease in exports, higher than the 12% drop in the EU27 as a whole. The difference is even more pronounced in imports: Spanish imports decreased by 18.2%, compared with 12.7% in the EU27.

The impact of product specialisation

The impact of COVID-19 on Spanish foreign trade has been analysed in a recent and interesting paper by Asier Minondo, of the University of Deusto. As Minondo points out, the greater impact on the export of Spanish goods and services, compared with other European countries, has been partly due to the Spanish economy’s product specialisation, in which services carry more weight (accounting for 30.8% of total Spanish exports, compared with 24.7% in European countries).

Additionally, within the services category, Spain has a high degree of specialisation in tourism, the sector most affected by COVID-19, as it is directly associated with physical contact between people. In terms of goods, one of the most negatively affected industries has been the automotive sector, which accounts for most Spanish exports.

The geographical structure of exports has also played a role. Exports of goods would have decreased by 1.6 percentage points less if the geographical distribution of exports had been the same as in France, Germany or Italy, according to Minondo’s study. Spanish exports have a higher rate of concentration in European markets (as well as in Africa and America).

Minondo analyses exports according to the business profile of the companies concerned. His conclusion is that exports could recover rapidly once the medical crisis caused by the pandemic is overcome. The reduction in exports has been mostly concentrated in the ‘intensive margin’, by which he means that the company continues to sell its products in a market, albeit in smaller quantities. The decline in exports has been less affected by the ‘extensive margin’, which is when a company completely interrupts its export activity.

The recovery of exports is easier if the decline is due to the intensive margin. The company sells less but maintains its relationships with its customers, making it easier to recover sales later. If the decline is due to the extensive margin, the company loses those relationships with its customers. It would then have to rebuild them or build new relationships, which is harder and more expensive to do.

Other data analysed by Minondo also support this interpretation. The drop in exports would have been even more worrying had it been accompanied by a decline in regular exporters. However, the number of regular exporters has remained practically unchanged between the first half of 2019 and the first half of 2020. Furthermore, the fall in exports has been more significant amongst large exporters, those who export the most. These companies are larger and therefore have more resources to regain their export activity.

A temporary impact or also a structural trend?

Is this relative optimism about a rapid recovery in Spanish exports justified? Admittedly, uncertainty is running high. And there is another factor that must be considered: as already noted, in the past two years both exports and imports of goods were experiencing a deceleration. The growth rate of exports fell to 1.8% in 2019, the lowest since 2011. Similarly, imports (always more volatile) grew by only 1% in 2019.

To what extent is the decrease in exports in 2020 a consequence of the COVID-19 disruption, or does it also partly reflect this deceleration, which is possibly a more structural trend as already witnessed in recent years? The question is difficult, if not impossible, to answer at present.

Minondo’s study is a useful contribution to our understanding of –and the ongoing debate about– the external trade sector, which has a great significance in Spain’s economy, but does not always receive the attention it deserves. It is striking, for instance, that in an important and useful recent report titled ‘For a political and social pact on a strategy of inclusive growth and reactivation’, published in September 2019 by the prestigious think tank Fundación de Estudios de Economía Aplicada (Fedea), written with the assistance of 130 experts, the external sector is practically absent. The report has no section devoted to the external sector or to internationalisation (with the sole exception of tourism), and the term ‘export’ or ‘exports’ appears only three times in the document’s 113 pages.

The external sector can significantly contribute to the Spanish economy’s recovery, and it must be given the attention it deserves. Regarding this subject, a paper published by the Spanish Exporters and Investors Club titled ‘Proposals to enhance the external sector as an engine of economic recovery’ can be highly recommended.