In a country that depends almost entirely on its oil exports it seems very strange that its leaders despise the national oil company. This, however, is precisely what is happening in Venezuela under the government of President Maduro.

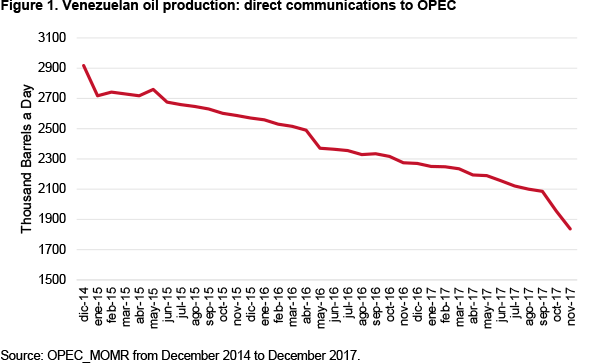

Between December 2014 and December 2017 Venezuelan oil production fell from 2.9 million barrels/day to 1.8 million as reported by the government to the Organisation of Oil Exporting Countries (OPEC). This implies a loss of over US$62 million a day, taking into account the average price of the Venezuelan oil basket in December.

A country that is currently undergoing one of the worst economic and social crises in its history would naturally look for ways to halt the decline in order to have access to this much needed foreign currency. Especially considering that according to the Venezuelan Central Bank (2015 data, the latest available official balance of trade statistics) 95% of its total foreign exchange revenue is generated by oil exports and that PDVSA’s total revenue accounted for around 37% of GDP in 2016 (using 2016 GDP estimates by Torino Capital and comparing them with PDVSA’s 2016 published financial results). All actions taken by the government, however, seem to further hinder any possibility of recovery.

“PDVSA has failed to offset the production decline of its traditional oil producing areas”

The decrease in production is a natural occurrence because oilfields become depleted. In order to offset this natural decline it is important to apply effective reservoir management techniques and invest in technologies for maximising recovery. On the other hand, companies should constantly develop new fields so as to ensure a stable total production. This is not what is happening in PDVSA. The company has failed to offset the production decline of its traditional oil producing areas. Such a decline is inevitable since they have been producing oil for over 100 years.

For the country that according to the International Energy Agency has the world’s largest oil reserves this should not be a major concern, given that the production loss can be quickly replaced by new fields. In the past years Venezuelan oil production has shifted from the traditional areas of the north-west to the centre-east where the Orinoco Oil Belt is located (the Faja as it is known in Venezuela), an area covering around 55,500 km². According to PDVSA’s 2008 operational report, oil production in the Faja accounted for 16% of total production that year and PDVSA’s 2016 operational reports show that it has grown to 50%.

In its 2017 annual statistical review, BP estimates that by the end of 2016, 222 billion barrels could be recovered from the region in an economically feasible way using existing technology (as a reference, Saudi Arabia’s total oil reserves stand at 266 billion barrels). The oil in the area, however, is extra-heavy, with an API grade below 10 degrees, and its production and transport therefore require additional efforts. In order to ensure the flow of crude towards the processing plants it needs to be blended with diluents. Initially another Venezuelan crude of higher gravity from the traditional oil fields of the north-west was used (Mesa 30) although, given the natural decline of these fields, the company started using refined products as diluents, particularly naphtha.

In the past three years the Venezuelan refining system has experienced many difficulties, largely related to ageing infrastructure and lack of investment, resulting in a dramatic drop in output. This forced PDVSA to start importing naphtha, and on some particular occasions light crudes, so as to keep the necessary flow of diluents for transporting oil from the Faja. These diluents should, theoretically, be recovered after treating the extra-heavy oil in the upgrading facilities and then sent back to the producing fields so as to maintain a constant flow. The upgrading capacity, however, has not increased at the same pace as the production of this extra-heavy oil, a large part of the production of the Faja is therefore exported with the diluents, as blended crude (naphtha with extra-heavy oil).

The fact that a large part of PDVSA’s production is tied to debt repayments, in addition to the scarcity of foreign currency due to the country’s extremely restrictive exchange control have given rise to an important cash flow problem for the company. This has in turn affected its capacity to import diluents in the required quantities to continue increasing oil production in the Faja to the levels needed to make up for the decrease in the traditional areas.

The Faja, on the other hand, is an inhospitable region, far from the country’s traditional oil centres and therefore lacking the necessary infrastructure to effectively operate the oil fields. Each new development requires hundreds of kilometres of different pipelines (for water, diluents, crude and natural gas) to allow the flow between the oil field and the processing plants. New roads are needed to link urban centres with the fields. This entails enormous investments, time and planning.

Most significant, however, is the need to have qualified personnel for each phase of the development. Unfortunately, PDVSA’s working conditions, where an engineer is paid a monthly salary equivalent to US$20, together with Venezuela’s deep social crisis have forced many qualified workers to leave the country. This, combined with the prioritising of political proselytism over technical qualifications, explains the general demoralisation of the majority of PDVSA’s employees. A few days after being appointed PDVSA’s new CEO, Brigadier General Manuel Quevedo publicly encouraged the workforce to engage in bullying and persecuting anyone not demonstrating unconditional support for President Maduro.

“All managerial posts, including the Board of Directors, have been assigned to people identified with President Maduro, regardless of their qualifications or experience”

All managerial posts, including the Board of Directors, have been assigned to people identified with President Maduro, regardless of their qualifications or experience in the oil industry. Nelson Martínez was the last high executive who had the necessary technical qualifications to solve the company’s serious internal problems, but he was ousted in November. During his short time in office he had to bear constant political attacks that did not allow him to devote himself to running the company. Additionally, the government imposed upon him a military executive vice-president, a few vice-presidents and an executive board with no knowledge of the oil industry, who reported directly to President Maduro and who constantly overruled any of his decisions.

In this very complicated context, it is impossible to develop the oil fields that might offset the natural production decline without the support of operating and financial partners. PDVSA’s partners who are still in Venezuela, however, have complained that they are not allowed to participate in the decision-making processes and that political judgement prevails over operating decisions. In addition, PDVSA has had significant delays in payment in the past years and many have opted to terminate the relationship. With regards to possible financial support, the recent sanctions imposed by the US, combined with PDVSA’s default on its international commitments, have destroyed the company’s credit rating and thus increased the cost of financing to unmanageable levels.

For all these reasons, the decline in total Venezuelan oil production has been unavoidable. Unfortunately, it seems that the trend will not only not be reverted in the short term but will worsen further. A few weeks ago, President Maduro launched a series of strong attacks against the company, claiming that PDVSA was responsible for the country’s current economic crisis. Using the attorney general, appointed personally by him, the government has presented dubious indictments and illegally detained technical executives of PDVSA. Those arrested have been accused on public television, with no right to legitimate defence and with no access to the prosecution files; furthermore, they have been isolated and have allowed no contact with their families. The workforce is demoralised and scared of political persecution, something that has been aggravated by the company’s militarisation, as it is now filled with uniformed military personnel and members of the National Guard who are close to the new CEO.

Given this context in which it is difficult to imagine production being restored, the stabilisation of oil prices might afford new opportunities to PDVSA. But in order to take advantage of the new situation it would vital for the company to focus on restoring the morale and technical capacity of its workforce, a necessary first step to address all other issues.