The EU’s annual report on Turkey’s accession negotiations, which have advanced at a snail’s pace since they were opened nine years ago this month, is like an end-of-term student report card. If an overall grade were to be assigned to Turkey it would be a C, with the comment that the government was trying harder but still had a long way to go to obtain the mark that would enable the country to join the EU.

Ankara has opened only 14 of the 35 policy chapters, and only one of them (on science and research) has been provisionally closed. The last chapter (on regional affairs) was opened last November, following a three-year hiatus.

Around half of the remaining chapters are either blocked because of French and Cypriot objections or frozen by Brussels because of Ankara’s failure to implement the 2005 Ankara Protocol and open its ports and airports to Greek Cypriot traffic and hence extend its customs union with the EU (since 1996) and recognise the Republic of Cyprus, an EU country since 2004. Turkey has occupied the northern part of Cyprus since invading the country in 1974.

The European Commission’s report, released on 8 October is less harsh than the previous one and, significantly, calls on member states to bury their objections and agree the opening benchmarks in order to start negotiations on two key chapters: justice and the rule of law. This would be a better way to lock Turkey into achieving progress in these vital areas and keep Ankara on board, rather than keep on shutting it out.

Signalling a less strident tone in its relations with Brussels, since the authoritarian Recep Tayyip Erdogan became president at the end of August after 11 years as prime minister (see Figure 1), Turkey’s Minister for EU Affairs and Chief Negotiator Volkan Bozkir called the report ‘objective’ and ‘balanced’, although there were some points he did not agree with. ‘We will take note of the fair and reasonable criticism and use it as a constructive element’, he said. Previous official reactions to the annual report were more hostile.

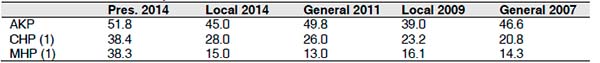

AKP = Justice and Development Party.

CHP = Republican People’s Party.

MHP = Nationalist Action Party.

(1) Joint ticket in the presidential election along with some other parties.

Source: Supreme Electoral Board.

The Commission is right to home in finally on justice and the rule of the law, as these areas are very weak and are at the core of Turkey’s lagging progress and the declining support EU-wide for the country’s full EU membership. Opening talks on these two chapters ‘would provide Turkey with a comprehensive road map for reforms in this essential area’.

The excessively brutal handling of the protests over Gezi Park, which rocked the country last year and particularly appalled Angela Merkel, Germany’s Chancellor (no great supporter of Turkey’s EU membership), the creeping Islamisation of Erdogan’s Islamist-rooted Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the government’s response to corruption allegations regarding senior officials and members of Erdogan’s inner circle have polarised the country.

‘The adoption of legislation undermining the independence of the judiciary, massive reassignments and dismissal of judges and prosecutors and even detention of a high number of police officers, as well as blanket bans imposed on social media’ are among the negative points made in the report.

The corruption allegations have turned the judiciary into a battleground between the government and what it calls a ‘parallel state’ affiliated to the movement of the US-based Islamic scholar Fethullah Gülen, once an erstwhile ally of Erdogan. Erdogan was happy to let the Gülenists serve his cause to weaken the military –once the arbiter of political life– by producing fabricated evidence and violating due process in the Sledgehammer trial that led to the jailing of 237 retired army officers in 2012 accused of plotting a coup. Once fully behind the charges, the fall-out with Gülen led the government to concede that there was a plot against the military. The Constitutional Court released all the officers in June 2014.[1]

The Commission also noted the government’s autocratic approach to passing new legislation, inherent in Erdogan’s majoritarian concept of democracy. ‘The tendency to pass laws and decisions, including on fundamental issues for the Turkish democracy, in haste and without sufficient consultations of stakeholders is a matter of concern’.

Fewer journalists are in prison than a year ago when Turkey ranked as the world’s top jailer, but media freedom is still very limited and censorship pervasive in one form or another.

Positive steps over the last year include the adoption of a plan to prevent violations of the European Convention on Human Rights and a package of measures for a peaceful settlement of the long-running Kurdish issue. Turkey’s Constitutional Court also overturned the government’s blanket bans on YouTube and Twitter, media widely used to spread the corruption allegations.

Now that Erdogan is installed in the presidency, after winning the country’s first direct elections for the post, the government needs to re-visit constitutional reform; it ground to a halt almost a year ago when the AKP pulled out of the talks with other political parties. A consensus was reached on around 60 of the 170 articles of the constitution that came into force in 1982 drawn up after the military’s last direct coup. Re-starting this process, the Commission said, ‘would constitute the most credible avenue for advancing further democratisation of Turkey, providing for the separation of powers and adequate checks and balances guaranteeing freedom, democracy, equality, the rule of law and respect for human rights, including the rights of people belonging to minorities’.

These are the issues that will decide whether Turkey makes the grade for EU membership. If Erdogan is really serious about membership remaining a long-term strategic goal, he knows what has to be done.

[1] The very detailed account of the trial by the Princeton University professor Dani Rodrik, the son-in-law of General Çetin Doğan, the alleged and freed leader of the coup, is devastating. See The Plot Against the Generals.