Turkey’s Islamist-rooted Justice and Development Party (AKP) lost its absolute parliamentary majority for the first time since sweeping to power in 2002, and with it Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s ambition for greater power by changing the constitution to become an executive president.

The autocratic Erdogan, three-time prime minister and the country’s first directly elected president as of 2014, won 258 of the 550 seats (327 in 2011), 18 short of a simple majority and far from the two-thirds majority (330 seats) he had hoped to win in order to call a referendum on the constitution and turn Turkey from a parliamentary into a presidential system.

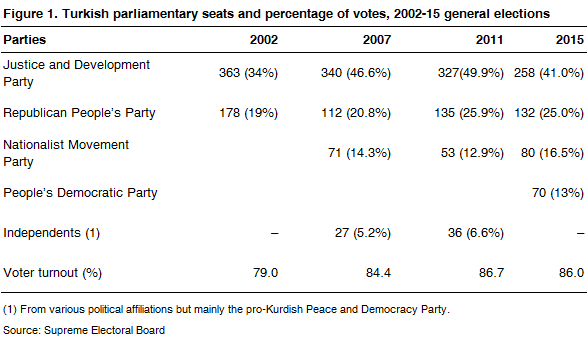

The AKP was still by far the largest party with almost 41% of the vote, but down from nearly 50% in 2011 (see Figure 1). Despite the abnormally high threshold of 10% of the national vote (3% in Spain) in order to be represented in parliament, the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP) stunned the AKP by winning close to 13% and 80 seats. Had it won fewer than 10% of the votes, its seats would have been forfeited and gone to other parties, which would have given the AKP an absolute majority.

The HDP’s gamble to run a unified slate instead of fielding independent candidates, as it had in the past, paid off. The 10% threshold does not apply to independent candidates. Erdogan accused the HDP of being a front for the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), which took up arms in 1984 in an insurgency that has killed 40,000 people and is still not definitively over.

The HDP’s leader, Selahattin Demirtas, broadened the party’s appeal to embrace liberal and secular Turks and it also fielded more female candidates than all the other parties. This was a strategy adopted to some extent by the AKP in 2002 when Turks deserted the ossified and corrupt elites of Kemalism (the ideas and principles of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder and first president of the secular Turkish Republic).

Since then the divisive Erdogan has alienated a significant segment of Turks with his Islamist agenda, identity politics, majoritarian concept of democracy, conspiracy theories and corruption in the AKP ranks. He knows how to win democratically, but not how to govern democratically. During the campaign he accused his opponents of being part of an international plot against Turkey and fulminated against the international media, particularly the New York Times, which he said was owned by ‘Jewish capital’. Erdogan broke the spirit of the constitution by campaigning heavily for the AKP. According to the constitution, the president is barred from any links with political parties once he takes office.

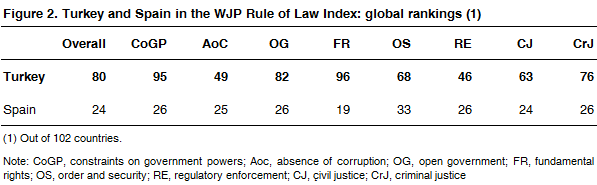

A recent European Parliament report on Turkey severely criticised the country on the subjects of independence of the judiciary, freedom of expression and freedom of the press. The country was ranked 80th out of 102 countries in the 2015 WJP Rule of Law Index (see Figure 2).

Another factor behind the AKP’s loss of support is the waning since 2014 of Turkey’s stellar economic growth. Unemployment is at a five-year high of 11% (masking a lot of underemployment) and per capita income has been stuck at around US$10,000 for several years. The country is over dependent on short-term capital flows, which can be pulled out as quickly as they arrive, and, like Spain, the economy has become too reliant on a booming construction sector. The lira has lost about 40% of its value since the Gezi park protests in 2013. Government debt, however, is only 33% of GDP and the budget deficit 1.4%.

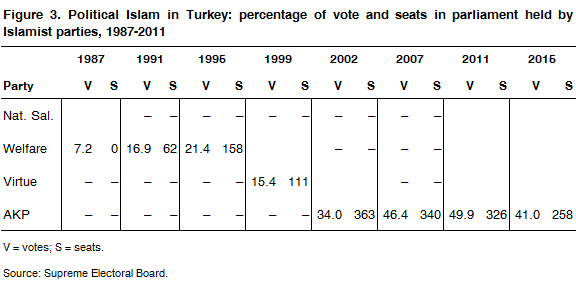

The erosion of the AKP (see Figure 3) heralds a period of difficult coalition negotiations, with no opposition party keen to get into bed with the AKP. The most likely candidate for a coalition with the AKP is the far-right Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), but it has already ruled this out, as has the HDP.

Should the sides fail to form a coalition, new elections are a real possibility and by law could be called any time 45 days from now.

A more tolerant and liberal government would help Turkey’s protracted negotiations to become a full EU member. The country, which has been nearly five decades waiting in Europe’s ante-room (it became an associate EEC member in 1963 and began accession negotiations in October 2005), has only opened 14 of the 35 ‘chapters’ or areas of EU law and policy needed to complete the process. It has closed just one of them (science and research). About 18 chapters (the key ones) are blocked or frozen, by the EU as a whole, or by some countries, most notably Cyprus.

In December 2006 the EU unanimously suspended eight chapters because Turkey refused to extend its customs union with the EU (in effect since 1996) and allow Greek Cypriot vessels access to its ports and airports, thereby recognising the state of Cyprus. The previous AKP government said it would not budge until the European Council (EC) fulfilled its promise to ease the economic isolation of the internationally unrecognized Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC).

Also bogged down are the seemingly endless negotiations between Greek and Turkish Cypriots to reunify Cyprus, divided since 1974 after Turkey’s invasion following intercommunal violence and an attempt to incorporate the island into Greece through a military coup.

A window of opportunity was opened with the election of the pro-reunification Mustafa Akinci in April as leader of the Turkish Cypriots. Akinci’s call for new relations between the TRNC and Turkey on more equal terms, however, drew a rebuke from Erdogan who told him never to forget who picks up the bill for supporting the territory.

Turkey is now in unchartered waters.