On 2 April President Trump announced an increase in the tariffs levied on practically all countries of the world, allies and enemies alike. Since that day, curiously dubbed ‘Liberation Day’, the US is set to apply additional tariffs of 34% on goods from China, 20% on those from the EU, 24% on Japan and so on successively. He introduced them by an Executive Order based the 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act, which bypasses approval by Congress (the institution that, in principle, establishes trade policy).

(…) there is considerable uncertainty and it would be unwise to expect the 10% tariffs (or greater) to fall over time; indeed, they are likely to remain in place for some time to come.

The new tariff structure starts with a minimum non-negotiable tariff of 10% levied on all countries and goods (except copper, semiconductors, wood, pharmaceutical products, critical raw materials that do not exist in the US, and energy and energy products, listed in Annex II), and is separate from a 25% tariff on automobiles. But there are also additional ‘reciprocal’ tariffs based on the Trump Administration’s sui generis interpretation of the trade barriers imposed by each of its trading partners on the US.

The trade barriers erected by each country (referred to as ‘Tariffs charged to the USA, including currency manipulation and trade barriers’ in the chart displayed by Trump) were not calculated using any scientific method, but are simply the coefficient of the trade deficit and the level of bilateral imports (or 10% in the absence of a deficit). The Department of Trade has supposedly included two elasticities in the formula (imports with respect to import prices and price-tariff elasticity), but these are not distinguished by country and cancel each other out. Once this coefficient has been calculated as the ‘theoretical tariff’, a US tariff is levied equivalent to half of this number, with a minimum of 10% (Figure 1). Canada and Mexico will continue to be subject to the 25% tariffs that have been applied hitherto, falling to 10% on the trade covered by the US-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), and 10% on energy products from Canada.

The ‘reciprocal tariffs’ number is thus totally arbitrary, although the Department of Trade has drafted a report with a qualitative list of trade barriers erected by a range of countries. Various details are worth highlighting. First, as is evident from Figure 1, the tariffs do not reflect any political consideration: a 10% tariff has been imposed on the UK not because of any special relationship with that country but because the UK has a trade deficit with the US; 17% has been imposed on Israel, despite a previous announcement that all bilateral trading tariffs with the US were going to be eliminated; Russia and North Korea have been exempted from the tariff, but mainly because there are no major trade flows (Ukraine, by contrast, is subjected to a general tariff of 10%). The tariff levied on EU products is 20%, calculated in a combined way (had a distinction been made between countries, Ireland, Germany and Italy would have suffered higher tariffs and the Netherlands and Spain lower tariffs; Hungary has failed to avoid the tariff). The tariffs have been particularly swingeing for Asian countries (as in the case of China, Japan and Vietnam), with which the US has major trade deficits. It is also worth drawing attention to the fact that all these tariffs are in addition to those already announced. For example, China’s 34% tariff comes on top of the 20% that Trump announced last month, which in turn is in addition to the raised tariff regime in place since the days of the first Trump Administration. Moreover, the 25% tariffs on steel and aluminium, announced last month, are also retained.

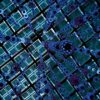

Figure 1. Some ‘reciprocal’ tariffs levied by the US (US$ mn)

| [1] | [2] | [3] | [4] = [3]/[2] or 10% | [5] = 50% [4] or 10% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | Imports | Balance | ‘Theoretical’ tariff (%) | US tariff (%) | |

| Australia | 34,594 | 16,685 | 17,909 | 10 | 10 |

| Brazil | 49,667 | 42,317 | 7,350 | 10 | 10 |

| China | 143,546 | 438,947 | -295,401 | 67 | 34 |

| Hong Kong | 27,887 | 5,974 | 21,913 | 10 | 10 |

| India | 41,753 | 87,417 | -45,664 | 52 | 27 |

| Israel | 14,792 | 22,218 | -7,426 | 33 | 17 |

| Japan | 79,740 | 148,209 | -68,469 | 46 | 24 |

| South Korea | 65,541 | 131,549 | -66,008 | 50 | 26 |

| Malaysia | 27,704 | 52,535 | -24,831 | 47 | 24 |

| Saudi Arabia | 13,178 | 12,734 | 444 | 10 | 10 |

| Singapore | 46,032 | 43,204 | 2,828 | 10 | 10 |

| Switzerland | 24,962 | 63,426 | -38,464 | 61 | 31 |

| Taiwan | 42,337 | 116,264 | -73,927 | 64 | 32 |

| UK | 79,943 | 68,084 | 11,859 | 10 | 10 |

| Vietnam | 13,097 | 136,561 | -123,464 | 90 | 46 |

| EU | 370,189 | 605,760 | -235,571 | 39 | 20 |

The Trump Administration’s neo-mercantilist logic views a trade deficit as bad per se, and sees a bilateral deficit as the consequence of protectionism and not specialisation. This viewpoint would lead to the absurd situation, if the same reciprocal tariffs formula were to be applied to services (where the US is a leader and maintains a surplus with most countries), that the EU ought to impose an 18% tariff on US services, China a 22% tariff and South Korea a 20% tariff, to cite only a few examples.

For macroeconomic purposes, the relevant balances are not bilateral but rather the global current account balance and this is not reduced with tariffs but rather with an increase in public and private saving with respect to investment. Moreover, it is unlikely that a policy that raises the cost and impedes imports of industrial inputs is capable of increasing net employment in a world of global value chains and with the growing preponderance of services.

Nor is it likely that the 10% base tariff will succeed in securing a structural increase in revenues, something that is essential if Congress –where there is a Republican majority but also concern about the high public deficit– is to approve an extension of the first Trump Administration’s tax cuts or additional cuts to, for instance, corporation tax or taxes on tips. The US collects very little from tariffs, around US$77 billion annually (the same is true of all advanced countries with sophisticated and progressive fiscal systems). It is hoped that the newly announced tariffs will raise up to US$800 billion, but it will undoubtedly be significantly less. Everything also depends on how the US’s trade partners react and where the final equilibrium settles, but wherever it is there will probably be much less trade between the US and the rest of the world.

The White House argues that the US trade deficit is due to the strength of the US dollar which, by virtue of being the global reserve currency, suffers excess demand and tends to appreciate. But despite Trump wanting a cheaper dollar to make the prices of physical US exports cheaper, the proposed tariffs will achieve exactly the opposite. By generating inflation in the US, they will force the Federal Reserve, its central bank, to raise interest rates (or to stop reducing them as it had planned), something that will inevitably strengthen the dollar. This would cancel out the improvement in the trade balance that is being sought with the imposition of tariffs.

Once the initial shock has subsided it is likely that tariffs in excess of 10% will be subject to concessions, whether economic or otherwise. In other words, they will be negotiable. It is conceivable that there will be a relocation of semiconductor production, for example, from Taiwan to the US or pharmaceutical products from Switzerland to the US. In any event there is considerable uncertainty and it would be unwise to expect the 10% tariffs (or greater) to fall over time; indeed, they are likely to remain in place for some time to come.

Regardless of this, the hike in tariffs has been considerable. Paul Krugman claims that it exceeds the increase the US imposed in the 1930s (the infamous Smoot-Hawley tariff, which helped to exacerbate the Great Depression). It should not be forgotten that the US starts from a relatively low level of tariffs (a non-preferential weighted average tariff on the rest of the world of 2.2%, distributed between 4% for agricultural and 2.1% for non-agricultural goods), so that transitioning to a minimum tariff of 10% (and a much higher weighted average) constitutes a veritable structural shock. Hence, as already pointed out, a major impact on US inflation is to be expected, to be borne predominantly by medium- and low-income consumers, many of whom form Trump’s electoral base (note that there are very high tariffs for countries such as Vietnam –46%– and Cambodia –49%– from where the US imports low added-value textiles and consumer goods).

For the EU, the fact that the tariffs have not discriminated between Member States will facilitate a coordinated response from the Commission. Meanwhile, the high tariffs imposed on Asian countries (higher in general than European countries) theoretically makes a coordinated response feasible.

The European Commission is obliged to respond to display its strength and try to negotiate to reach a settlement, none of which seems straightforward. It is essential for tariff increases to be imposed with surgical precision and on goods produced in states where the Republicans secured narrow victories (the so-called swing states, such as Wisconsin and Pennsylvania). A cut in interest rates from the European Central Bank could weaken the euro and boost internal demand to make up for the negative impact on demand stemming from Trump’s tariffs. If it came down to it, it may be necessary for the first time to resort to the Anti-Coercion Instrument, approved at the end of 2023, which enables drastic non-tariff measures to be taken, although it would be wise to use it cautiously with services and financial transactions, given that dependency on the US (in strategic services, for example) is considerable. In any event, it is worth pointing out that this instrument would take several weeks to put into practice, since it requires an investigation on the part of the Commission and a qualified majority of the European Council. The European Commission hopes that its activation will enable negotiations to get under way.

In the medium term it will be difficult for trust in the US as a trading partner to be restored, so efforts will need to be invested in diversifying export markets and reducing risks, given that tariffs are surely here to stay. The US ‘Liberation Day’ provides yet another incentive to make headway along the path of the EU’s open strategic autonomy.