When China joined the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001, it was still a developing country. More than 15 years later, its circumstances have changed and it has turned into the world’s second-largest economy. The WTO has served not to discipline China, which is what Trump (and to some extent the EU, albeit more discreetly) seeks, but rather to globalise it. And Trump wants to stop China overtaking the US technologically. Underlying the trade war –because what was a minor spat has become just that– unleashed by the current US President there is a conflict of perceptions. It is said that Trump sees China as a wealthy country with many poor people, while China sees itself as a poor country with many wealthy people.

The conflict of perceptions, complete with political consequences, goes beyond this. The Trump Administration, now featuring a more coherent and streamlined team, views Europe as a group of wealthy countries that the US defends at its own expense. This is why it is asking the Europeans to spend more on their defence, with the catch that they buy US weaponry. The EU will spend more, but predominantly on their own systems. Thus, if the €13 billion earmarked by the European Commission for the new European Defence Fund is approved, it will be spent on European projects.

The Trump Administration also views Europe through the prism of Germany, a country with a trade surplus that is first and foremost a concern for Germany’s own partners in the EU. US tariff increases are thus essentially aimed at Germany, with the sword of Damocles hanging over the automotive industry, a fundamental component of German exports. The Trump Administration perceives the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) with Canada and Mexico not only as outmoded (it is, having been signed in 1992) but as having benefitted its two partners more than the US, which is more than debatable.

The Europeans, meanwhile, tend to view Trump more as a cause than a symptom of what’s going on: yet another conflict of perceptions that makes it more difficult to find solutions. From the EU perspective it should not be assumed that if Trump loses the next elections, due in 2020, US trade policy will undergo substantial change; first, because at this juncture nothing guarantees he is going to lose and, second, because the Democrats do not embrace free trade with any great enthusiasm either, less still when the US victims of free trade (in terms of their jobs and salaries, although not as consumers) have mainly voted for Trump.

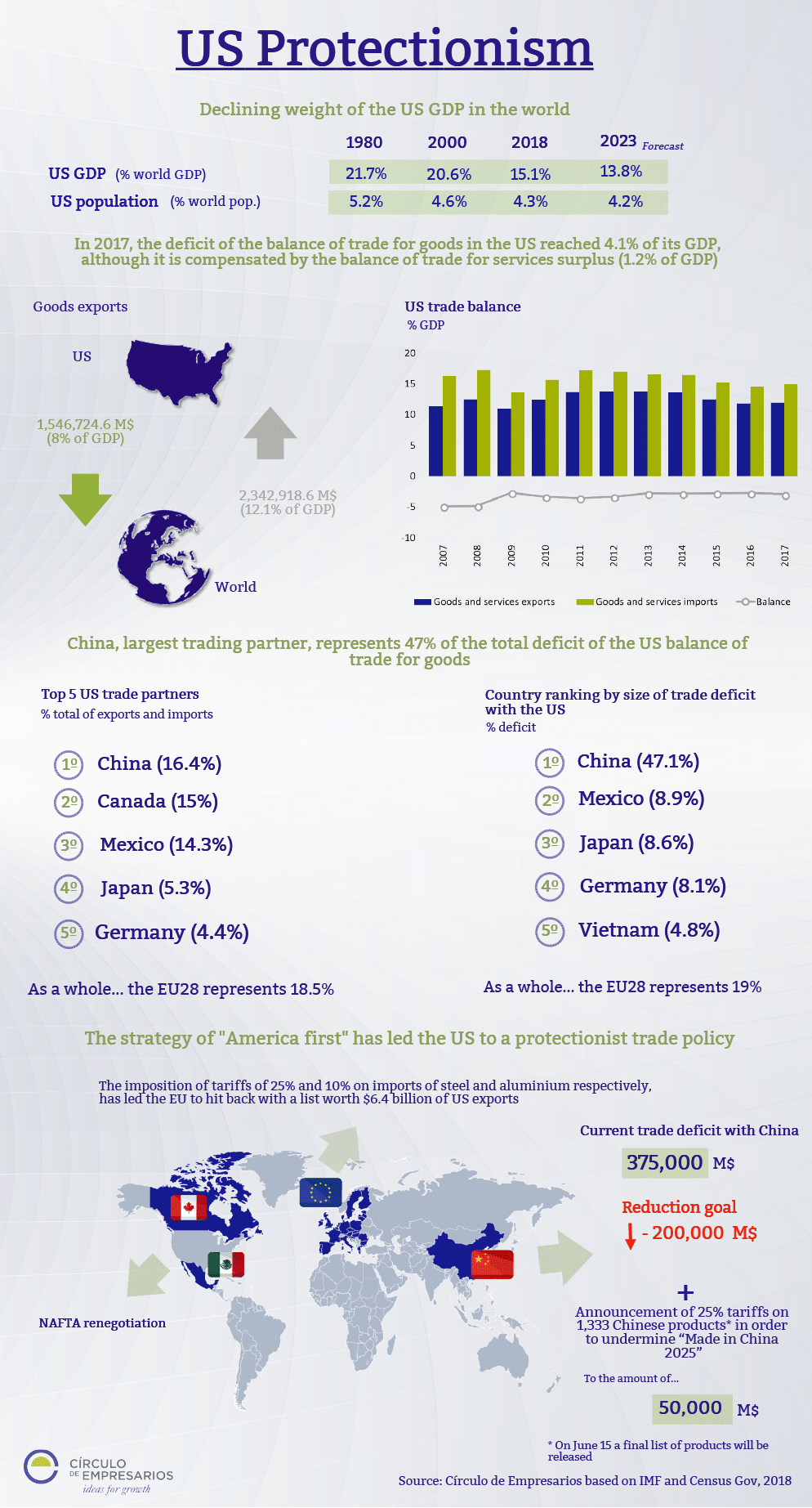

According to data published by the Círculo de Empresarios, the main countries with which the US runs a trade deficit are China (47.1%), Mexico (8.9%), Japan (8.6%), Germany (8.1%) and Vietnam (4.8%). With the EU as a whole the figure is 19%. But the statistics tend to reflect an outdated model. Digital transactions do not appear in many reckonings, nor does a growing and currently crucial component of such transactions, namely the trade in data, which is not covered by the WTO. The rules applied offline are not the same as those applied online, although regulations are increasing in the latter domain.

The Trump Administration has used national security as the pretext for its protectionism. But, in point of fact, what does national security have to do with, for instance, importing cars (or olives) in peacetime? As the German Foreign Minister, Heiko Maas, likes to point out with more than a hint of irony, American streets and freeways ‘are more secure with German cars’. Moreover, Trump has deadlocked the WTO, where all such disputes are supposed to be settled. For the last year he has vetoed all judicial appointments to the organisation’s seven-member appeals chamber, which is charged with resolving trade quarrels.

That said, the WTO is in dire need of in-depth changes. As Pascal Lamy, the WTO’s Director-General between 2005 and 2013, pointed out at the recent Global Solutions 2018 in Berlin, the WTO is an organisation in which its member states rule supreme. In other words, its board and Director-General (by contrast to the UN, or indeed the EU) have little scope for taking the initiative. In this respect, and others, change is in order.

Many of these problems predate Trump. Not everything can be laid at his door. The WTO has achieved little in terms of multilateral trade agreements since 1994. Thus, previous US Administrations, including Obama’s, favoured bilateral treaties, with the exception of the transpacific (TPP) and transatlantic (TTIP) treaties. The latter was undermined in the 2016 election campaign not only by Trump but also by his Democratic rival, Hillary Clinton. It has become evident that the G7 is not the appropriate forum to start settling these issues. But the G20 is unlikely to be either. They are useful for expressing disagreements, talking and clearing the undergrowth. But institutions are needed, a requirement that neither the G7 nor the G20 fulfils.

Lamy argues that we need a new agreement, a new balance, on globalisation. It is worth remembering that between 1870 and 1914 globalisation survived because, in the English-speaking world at least, an alliance or coalition was formed between liberalisers and social reformers, as Suzanne Berger has astutely pointed out. These days there are protectionists, but the social reformers are less prominent.

Are we witnessing a process of de-globalisation? With the exception of digital trade, mentioned above, global commerce and the flows of international investment are now slowing down according to UNCTAD’s latest World Investment Report. And this comes at a time when, as Jorge Argüello of the Argentine think tank Embajada Abierta points out, the costs of de-globalisation are higher than 20 or 30 years ago: and that goes for all of us.