Spain’s ratification of the Paris Agreement –with the government now committed to developing a Climate Change and Energy Transition Law–, the opportunities opened up by a gradual and orderly energy transition, and a public opinion increasingly demanding action on climate change, are three compelling reasons for the approval of an ambitious law in alignment with international climate commitments.

(1) International commitment and litigation for inaction

Since 1994, legislative and executive initiatives taken on climate change have multiplied 20-fold globally.1 There are currently more than 1,300 climate-change laws around the world, proof of a growing concern for the effects of climate change. The Paris Agreement is expected to lead to an increase in international climate legislation. This is because many countries made the commitment in Paris to introduce new climate legislation. Since the 1990s there has also been a significant rise in the number of climate litigation cases around the world, and it is to be expected that improvements in the science of attribution2,3 might result in more climate-related litigation. Inaction on climate change, and a failure to align with the objectives of the Paris Agreement, could land governments and companies in court.4

How do the two trends affect Spain? At the beginning of 2017, Spain ratified the Paris Agreement. The agreement’s aim is to limit increases in the average global temperature to well below 2ºC above pre-industrial levels –and to make efforts to limit the increase to no more than 1.5ºC–. The Paris Agreement also sets out to achieve net zero carbon emissions (that is, a balance between emissions and the absorption of GHG emissions) sometime during the second half of the century.

To comply with Spain’s international climate commitments would require aligning the Climate Change and Energy Transition Law (which Spain committed to approving before the end of the legislature) with the Paris Agreement. Therefore, the objective of limiting average global temperatures and the objective of achieving carbon neutrality should be incorporated into the laws that –like Spanish legislation– are currently being developed or updated. Other countries are already including the carbon neutrality goal in their climate-change legislative frameworks. A good example is Sweden, the first country to include the goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2045. Other countries that have incorporated the net zero carbon goal include France, Iceland and New Zealand.

On the other hand, the Paris Agreement calls on countries to take action based on the best available scientific data. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), along with other institutions, provide information to facilitate international climate negotiations. Furthermore, independent scientific institutions at the national level have been advising their governments on decarbonisation goals for over a decade. For instance, the Committee on Climate Change in the UK proposes emission reduction targets to the government,5 reports on progress towards achieving objectives, analyses risks stemming from climate change and suggests adaptation strategies. The means to achieve the objectives are then determined at a political level.

Although Spain does not have a strong tradition in developing these types of independent institutions, the creation in Spain of a body like the UK’s Committee on Climate Change (sufficiently resourced and adequately budgeted to carry out its mandate and to which the government would be obliged to respond) would be very useful for devising decarbonisation strategies that are scientifically sound and capable of minimising the potential politicising of decarbonisation transition processes.

(2) Opportunities for action and the risk of inaction

When they presented the Report of the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices, Joseph Stiglitz and Nicholas Stern claimed that the economy of the 21st century would be dynamic, innovative and low-carbon. Hence, their suggestion was to decide where we should be in such an economy in the future and what the risks would be of being left behind in the sixth wave of innovation.6 The latter involves sustainability, resource efficiency, the biomimetic (or biologically-inspired) design of goods and services (to successfully implant a development model based on the circular economy), and the development of renewable energies, among others.

More than a mere climate accord, the Paris Agreement and the climate legislation that it develops and fosters –and in a broader sense, the transition to a lower emission economy– is a change in economic model unseen since the Industrial Revolution… but only if action is taken swiftly and decisively. The change would benefit countries and companies with less exposure to carbon risk and that manage the low-carbon transition in a gradual and orderly way.

In Spain, many companies recognise the opportunities created by the transition to a low-carbon economy. In a recently published manifesto, 32 companies7 in the Spanish Green Growth Group asked the government to approve without further delay an ambitious Climate Change and Energy Transition Law. They want a fiscal framework that follows the polluter-pays principle and the gradual elimination of fossil-fuel subsidies. They also want decarbonisation targets for 2030 and 2050 that provide some certainty to investors and that are aligned with the Paris Agreement. They additionally call for an independent body, similar to the Commission on Climate Change in the UK, to guarantee compliance with Spain’s climate commitments. In addition, the signatories want financial flows to be aligned with climate objectives and transparency measures to be established for private-sector carbon-risk exposure.

Both (1) the adoption of the recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFP)8 and (2) the adaptation of article 173 of the French Law for Energy Transition to the Spanish economic context and its integration into the future Climate Change and Energy Transition Law would facilitate the reorientation of financial flows towards low-carbon investments. The recently-published European Commission Action Plan on financing sustainable growth also focuses on the same aim. Specifically, the EC action plan’s four-fold objective entails reorienting capital flows to sustainable investments, integrating sustainability into risk management, increasing transparency and fostering long-term decision-making. To meet these objectives the Commission will: (a) develop a taxonomy of sustainable assets and projects; (b) devise labelling and certification schemes for green financial products; (c) clarify the obligations of both investors and asset managers; and (d) incorporate sustainability considerations into prudential requirements, for which the use of Green Supporting Factors or Brown Penalising Factors, among others, are being considered.

(3) Public opinion

Finally –and perhaps of political significance for the local, regional and European elections of 2019–, concern for climate change as one of the greatest threats to the world is rising at the global, European and Spanish levels. Furthermore, as shown by the analysis of the Elcano Royal Institute (2017), climate change is the second most important foreign policy priority for German, French and US public opinion, right after combating international terrorism. Among the Spaniards surveyed, climate change is the top foreign policy priority, over and above the fight against jihadist terrorism (Elcano Royal Institute, 2018).9

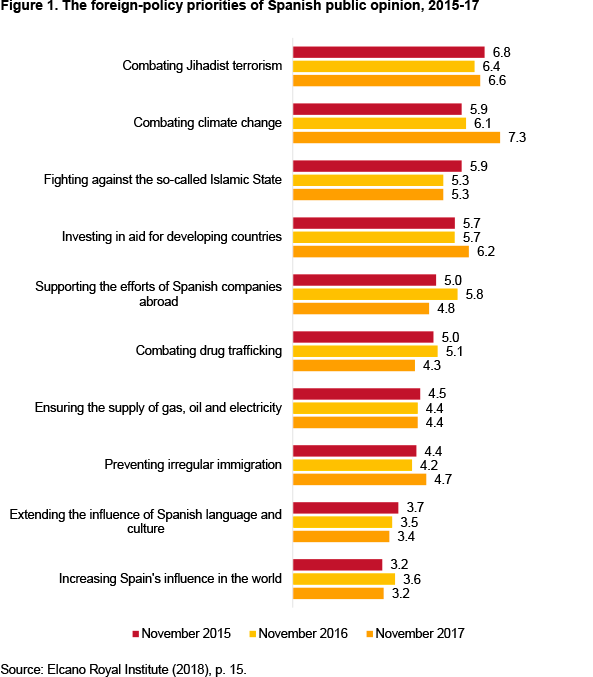

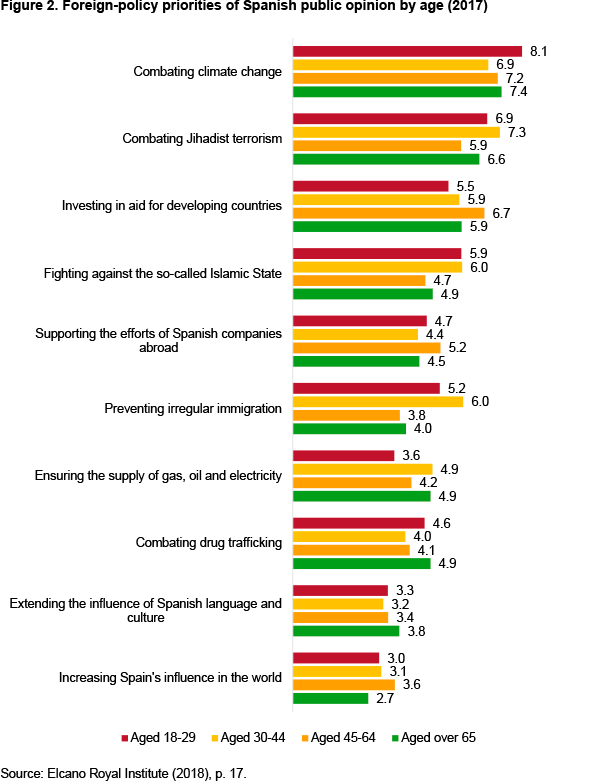

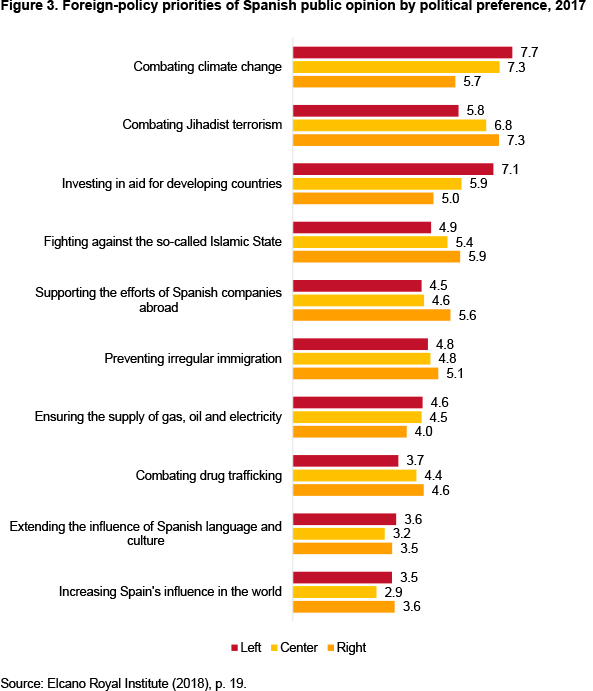

Figures 1, 2 and 3 show a breakdown of the foreign policy priorities of Spanish respondents from November 2015 (just before the COP21 in Paris) to November 2017 (Figure 1), with a breakdown by age in 2017 (Figure 2) and by political preferences in 2017 (Figure 3).

As shown in Figure 1, climate change as a foreign-policy priority has steadily grown in importance for Spaniards between 2015 and 2017, a year marked by extreme weather events.

Figure 2 shows that for all age groups the fight against climate change is the top foreign-policy priority except for those aged 30 to 44, for whom fighting climate change is the second priority after combating jihadist terrorism.

The data from Figure 3 reveal that for both voters at the centre and the left of the political spectrum, the fight against climate change is the top foreign-policy priority. For voters on the right of the political spectrum, climate change is the third most important foreign-policy priority.10 In summary, public opinion is much concerned about climate change as a global threat and wants the foreign policy focus on climate change to be a top priority.

To be a credible partner, who complies with international climate commitments, Spain needs to take up the opportunities offered by the low-carbon economy to respond to business and public opinion concerns about climate change and to an increasing demand that it prioritises combating climate change in its foreign policy. It must therefore approve the announced Climate Change and Energy Transition Law in accordance with the Paris Agreement and as soon as possible.

1 A. Averchenkova, S. Fankhauser & M. Nachmany (2018), Trends in Climate Legislation, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham.

2 The science of attribution analyses the variation in the likelihood and seriousness of two meteorological phenomena due to human-induced climate change, assigning them a degree of statistical confidence. See S. Marjanac, L. Patton & J. Thornton (2017), ‘Acts of God, human influence and litigation’, Nature Geoscience, nr 10, pp. 616-619.

3 National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (2016), ‘Attribution of Extreme Weather Events in the Context of Climate Change’, Committee on Extreme Weather Events and Climate Change Attribution Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate, Division on Earth and Life Studies.

4 H. Covington, J. Thornton & C. Hepburn (2016), ‘Shareholders must vote for climate-change mitigation’, Nature, nr 530, p. 156.

5 The five-year carbon budgets are approved sufficiently in advance to avoid the short-term thinking imposed by the political cycle.

6 S. Nair & H. Paulose (2013), ‘Emergence of green business models: the case of algae biofuel for aviation’, Energy Policy, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.enpol.2013.10.034i.

7 The 32 signatory companies are ABERTIS, ACCIONA, ASOCIACIÓN FORESTAL DE SORIA, BANKIA, BBVA, CLIMATE STRATEGY, CONTAZARA, ECOACSA, ECOALF, ECOEMBRES, ECOTERRAE, ENDESA, EULEN, FERROVIAL, FRATERNIDAD-MUPRESPA, IBERDROLA, IKEA, INCLAM, INECO, LAFARGEHOLCIM, LOGISTA, MAPFRE, NH HOTEL GROUP, OHL, REE, SICASOFT SOLUTIONS, SIEMENS GAMESA, SINCE02, SUST4IN, TEIMAS, TELEFÓNICA and WILLIS TOWERS WATSON.

8 A working group on financial communication and climate change in the G20’s Financial Stability Council.

9 It should, however, be borne in mind that historically the CIS barometer registered environmental concerns as only marginally relevant. One of the reasons for the apparent discrepancy between the CIS survey data and that of the PEW analysis (Poushter y Manevich, 2017), the European Commission (Eurobarometer) and the Elcano Royal Institute is that the latter surveys ask about ‘threats to the world’ (Eurobarometer), ‘threats to the country of the person surveyed’ (Pew) or ‘foreign-policy priorities’ (Elcano Royal Institute). The CIS asked about ‘the three main problems facing Spain today’, highlighting unemployment, corruption, politicians and healthcare, among other issues.

10 After combating jihadist terrorism and fighting against the self-proclaimed Islamic State.