The decline of a section of the middle classes in the west could be behind the electoral upheaval and the growth of populism in a large number of societies, but what is the truth of the matter? And if it is the case, what accounts for it? Globalisation? Technology and automation? Domestic –European in the case of the EU– public policies, or the lack of them? It is an important issue. The fact that it has not been resolved does not mean that it is devoid of political impact.

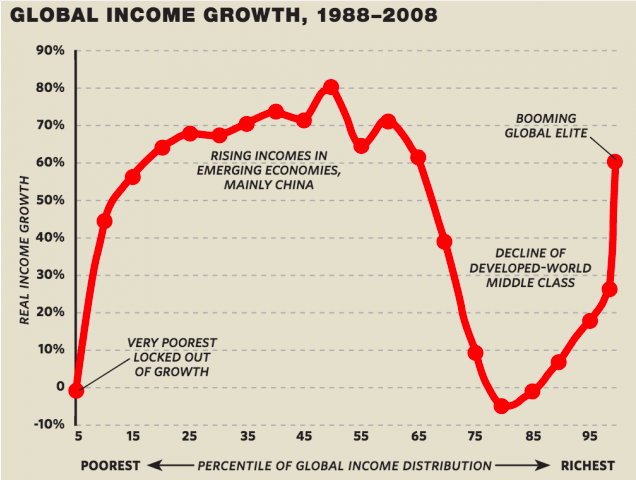

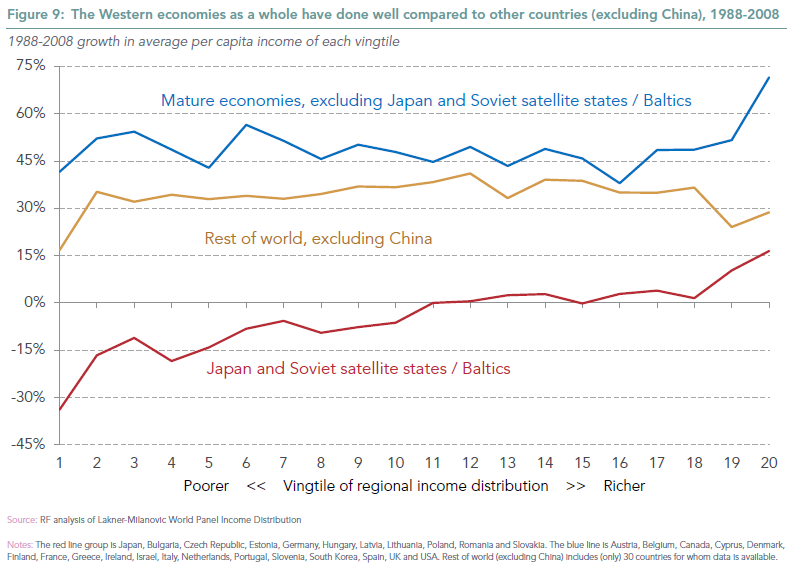

Drawing on a vast database, Branko Milanovic of the World Bank has reached two main conclusions for the period 1998-2008: inequality (as well as absolute poverty) has fallen at a global level, in other words between countries (although much less if one leaves out China and the countries of the former Soviet Union), and the middle classes have grown worldwide; but inequality in the western world has increased, and the middle classes are in decline. This is shown by a graph that, because of its shape, has been dubbed the elephant curve.

A paper published by Britain’s Resolution Foundation questions this interpretation of the data and concludes that the western middle classes have not lost ground during the period, although growth has been uneven, particularly in the US. The situation varies a great deal between countries, however. Above all, the analysis stresses the need to be circumspect when it comes to attributing such negative tendencies –which feed into public debate, including from the IMF– to global forces, in other words globalisation. The latter brings both opportunities and risks, and has lifted hundreds of millions of people out of poverty. It is also necessary to examine public policies (essentially domestic policies, including in the EU) on welfare, housing and the economy, and their impact on inequality and the western middle and working classes.

One problem with these studies is that they end in 2008, in other words when the Great Recession really began. Milanovic himself has extended the figures to 2011, examining with John Roemer the ‘Interaction of global and national income inequalities’, with the provisional conclusion that national inequality may have fallen in mature economies.

The International Labour Organisation, in a joint study with the European Commission, reaches the opposite conclusion: that growing inequalities in recent years have led to the reduction of the middle classes in Europe.

Another report, this time from McKinsey and appropriately titled ‘Poorer than their parents?’, argues that real incomes in advanced economies between 2005 and 2014 stagnated or fell for 65%-70% of households, accounting for more than 540 million people. The report gives data for a range of countries, although Spain is not among those included in the study.

McKinsey adds a deeply disturbing conclusion: ‘even a return to strong GDP growth may not eliminate the flat or falling trend as demographic and labour factors weigh on incomes’. In other words, even if there is growth not everyone will benefit from it, owing to the decline in a section of salaries (which in Germany started long before the crisis with the reforms introduced by Schröder). But the IMF does not even foresee such a return, but rather weak growth.

The latest data from the US however indicate that 3.56 million Americans emerged from poverty last year and the middle-middle and lower-middle classes are finally benefitting from the economic recovery, with a median (not mean) increase in household incomes of 5.6% in 2015.

But one must be careful with statistics, for instance those relating to unemployment. This is the approach taken by Nicholas Eberstadt in a book that has been reviewed and praised by Lawrence Summers; in Men without Work (“men” refers literally to men, not women) Eberstadt concludes that the extremely low rate of unemployment in the US (4.9% at the latest count) conceals the hidden unemployment of those who have lost work to machines or have simply given up looking for work, and are therefore not included in the statistics. They comprise one in every six men aged between 25 and 54. Although the situation in Spain is different, the active population (according to data from the National Institute of Statistics) has shrunk rather than grown: it has gone from 23 million people at the end of 2008, when the crisis began, to 22.8 million today, due in part to the people who have stopped seeking work, immigrants who have returned to their countries of origin and Spaniards who have gone to work abroad, among other factors.

In any event, perceptions weigh as heavily as reality when it comes to the political impact of this important issue of the loss of social status in the west. According to a Gallup poll, the percentage of people in the US who consider themselves working class has remained relatively stable since 2008, but the percentage of those who identify themselves as middle class has fallen by almost 10 points, from 60% to 51%. And this, the study concludes, is why politicians focus less on economic opportunity (not many years ago, in a striking demonstration of optimism, 20% of Americans claimed that they belonged to the wealthiest 10%) and more on fear, including the fear of losing identity.

In Spain, according to a poll conducted by MyWord in January 2015, 26.6% of people believed they had passed from the middle to the lower-middle class; 10.9% from the lower-middle to the lower class, and 4.3% from the lower class to the fear of falling into poverty. In other words, counting those who report having fallen from the upper to the middle class, the poll suggests that 47.9% of people felt they had dropped down the social ladder, while 37.5% reported no descent. This may help to explain many things.

The general conclusion arrived at by Dani Rodrik, one of the first to draw attention to this contentious issue, is illuminating:

‘The frustrations of the middle and lower classes today are rooted in the perception that political elites have placed the priorities of the global economy ahead of domestic needs. Addressing the discontent will require that this perception is reversed’.