The evolution of Spain’s economy over the past 750 years to its current position as the world’s 15th largest in terms of nominal GDP (and 34th in per capita GDP) has been a long and winding road, with alternating periods of stagnation and growth.

Leandro Prados de la Escosura, one of Spain’s leading and most distinguished economic historians, sets out in his recent book, A Millenial View of Spain’s Development (Springer, available free at Open Access), how economic progress and wellbeing have been achieved since the de facto end of the Reconquista in the mid-1260s (the recapture of Muslim territories by Christians).

Average income multiplied by more than 20 times over that period, but most of the gain was achieved in the last 200 years. Historians do not dispute Spain’s relative backwardness, compared with, for instance, north-western European countries, but they do not agree as to when it originated. Was it the result of the impact of the Black Death (1348), did it flow from the decline of Imperial Spain in the 17th century or was it due to other factors?

The author divides his investigation into two epochs, with 1850 as the dividing line. The first one saw long and deep swings in average incomes and, the second, sustained improvement in per capita GDP. He shows that population and economic growth evolved simultaneously, challenging the Malthusian theory which held that populations inevitably expand until they outgrow their available food supply, causing the population growth to be reversed by disease, famine, war or calamity. As it turned out, capital accumulation and productivity gains overcame the Malthusian constraint, enabling both higher population and income levels.

Spain was what is known as a frontier economy, with an abundance of natural resources (in its case wool) and a shortage of labour. It had one of the lowest population densities and one of the highest urbanisation rates in Europe. As a result, the amount of land available per worker was much higher than in the rest of Europe. This high land-labour ratio favoured the development of a pastoral system that was intensive in land use and low in labour use. Because of this, the Black Death had a devastating impact on an economy sensitive to changes in its scarce resource of labour.

Moving on to the late 16th and early 17th centuries, another probable explanation for Spain’s decline was its efforts to maintain its costly European empire through increasingly expensive wars (the Low Countries rebellion of 1567 and open war after 1573 and the Lepanto battle in 1571 against the Ottoman forces).

The Peninsular War (1807-14), known in Spain as the War of Independence, also had negative consequences, albeit short run. The war’s demographic impact caused a fall in the population to one million short of its potential and there were around 500,000 casualties, 5% of the population, which made it the bloodiest conflict in Spain’s modern history. That war also triggered the fight for independence in Spanish America, with the consequent impact on trade, manufacturing and government revenues. But it also sparked a complex transition from an absolutist empire to a modern nation, which redefined property rights, gradually shifted control of the executive to parliament and produced a more efficient allocation of resources.

Over the past 70 years, there have been three phases: the so-called ‘Golden Age’ (early 1950s to 1974); from the end of the Franco dictatorship (1975) to the start of the Great Recession (2007); and from then to the present. The 1959 Stabilisation Plan was key, as it moved Spain from 20 years of inefficient autarchy and statist orientation to a more open and market-friendly economy. The advent of mass tourism as of the 1960s, which Spain practically invented, was particularly important as it generated much needed foreign exchange earnings.

Political stability enabled long-term planning, encouraged gross capital formation and made macroeconomic management more predictable. This is not a justification of the Franco regime, but we should not forget that Spain suffered 53 coups between 1812 and 1935, seven constitutions and the three Carlist civil wars. By the time Franco assumed the position of head of government during the 1936-39 Civil War, there had been 145 heads in the previous 100 years. Peace is one of the prerequisites for prosperity recognised by Adam Smith.

Economic output grew nearly five times faster during the ‘Golden Age’ than in the previous 100 years and almost twice as much from 1975 to 2007. Since 2008, GDP has stagnated as a result of the Great Recession (2008-13) and the COVID pandemic, but the economy is now growing briskly.

Taking a much longer view, between 1850 and 2020, the population multiplied over three times, hours worked per person shrank by one-third and output per hour worked rose 24-fold (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. GDP growth and its composition, 1850-2020 (annual average logarithmic rates, %)

| GDP | Population | Hours worked per head | GDP per hour worked | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1850-2020 | 2.3 | 0.7 | -0.3 | 1.9 |

| 1850-72 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| 1873-92 | 1.3 | 0.4 | -0.3 | 1.2 |

| 1893-1913 | 1.2 | 0.7 | -0.1 | 0.6 |

| 1914-19 | 0.5 | 0.8 | -0.4 | 0.1 |

| 1920-29 | 4.1 | 0.9 | -0.3 | 3.5 |

| 1930-35 | 0.0 | 1.5 | 0.0 | -1.6 |

| 1936-39 | -6.6 | 0.4 | -1.0 | -5.9 |

| 1940-45 | 2.8 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 2.1 |

| 1946-53 | 3.4 | 1.0 | 0.3 | 2.1 |

| 1954-58 | 5.7 | 0.8 | -0.1 | 4.9 |

| 1959-75 | 6.4 | 1.1 | -0.9 | 6.2 |

| 1976-85 | 2.5 | 0.7 | -3.8 | 5.6 |

| 1986-2007 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 1.8 | 1.0 |

| 2008-13 | -1.3 | 0.5 | -3.4 | 1.7 |

| 2014-23 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 1.1 | 0.4 |

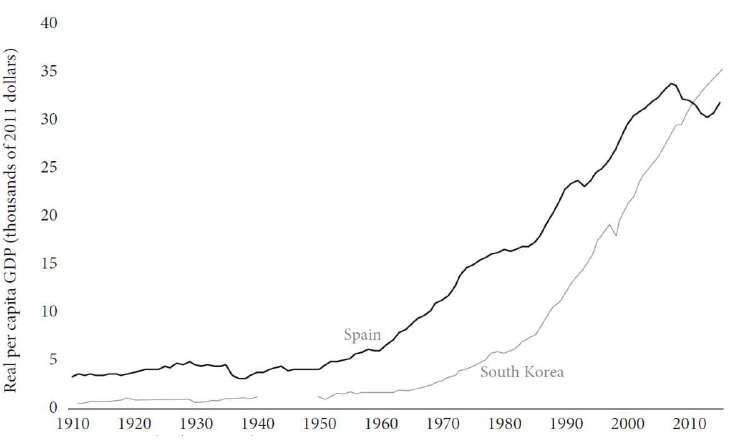

Spain is one of very few nations, along with South Korea, that has successfully transitioned from middle-income (per capita GNI of US$1,036 to US$12,535) to high-income status (see Figure 2), recounted by Óscar Calvo-González, a Spanish economist at the World Bank, in his equally enlightening book Unexpected Prosperity (OUP) published in 2021.

Figure 2. Spain and South Korea’s real per capita GDP

Prados’ book has chapters on capital accumulation, productivity growth (sluggish over the last 20 years), inequality and poverty, the loss of the American Empire, the terms of trade between Spain and Britain and the Industrial Revolution, and Spain’s financial position in the first globalisation, embellished with a mass of fascinating statistics.

The book deserves a long shelf life as a standard text on how Spain arrived economically at where it is today.