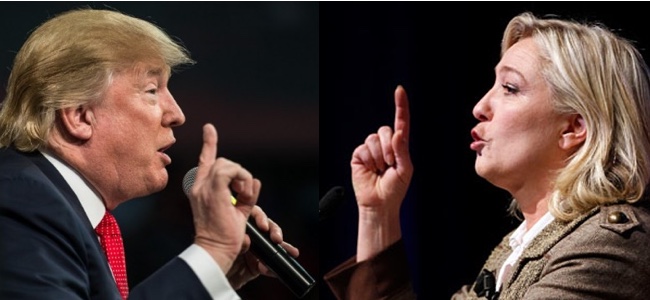

A nightmare scenario is causing some serious concern: seeing Donald Trump become US President in 2017 while Marine Le Pen becomes President of France, two processes that bear certain similarities. Writing about such a nightmarish possibility, Gideon Rachman, a Financial Times analyst, adds a third player: Vladimir Putin in Russia (much admired by Le Pen). Although neither scenario seems likely to materialise, they have both tainted the general political discourse in the two countries, among Trump’s and Le Pen’s followers and even beyond, with rants against immigration, Islam and, in France’s case, even Europe. The waters have been further muddied by the recent terrorist attacks in Paris and San Bernardino and by the appeal to fear. Extremism is now polluting the French political centre, both left and right.

Hand in hand with the crisis, with wages in real terms stagnant for decades for most citizens and an increasing cultural and racial mix (although traditionally immigrants tend to blend in and want to become ‘American’, contrary to what occurs in Europe), US society has radicalised in recent years, as shown in a study by the Pew Research Center. Although divided, Republican voters today are further to the right, which partly explains the Trump phenomenon, while the Democrats have moved further to the left. Up to 41% of the latter define themselves today as ‘liberal’ in the American sense, compared with 27% in 2000, and Bernie Sanders has forced Hillary Clinton to turn leftwards. Today 94% of Democrats are to the left of the Republican median and 92% of Republicans are to the right of the Democrat median. So there is a growing gap between Democrats and Republicans and an increasing polarisation of the electorate, with a vanishing centre that matches the relentless collapse of the middle classes.

Will Trump be elected Republican candidate for the White House? Many commentators suggest such a thing is impossible. But not totally. A poll in the New York Times suggests that he has the support of 35% of Republican voters (and his closest rival, Ted Cruz, of only 16%). If he does win the nomination, his discourse against Mexican immigration and now against Muslims, who he wants barred from entering the country, will ensure he never reaches the White House, as noted in an earlier Global Spectator. His nomination would serve Hillary Clinton the Presidency on a silver platter.

In France the regional elections have been a shock to many. In the first round, Marine Le Pen’s National Front (FN) came first in six of the country’s 13 regions, with 27% of the vote, while it garnered 28% (a further 800,000 votes) in the second round. In the latter round she was unable to capture any of the regional governments because of a greater mobilisation of centre-left and centre-right voters –their turnout was up eight points– and the decision of some candidates to withdraw in order to back the best placed. It has, nevertheless, been Marine Le Pen’s and the FN’s best result ever by number of votes, even more so than in the presidential elections of 2012, when she took 17.9% of the vote.

This particular Le Pen has both a new discourse and a new sociology behind it. The enemy is now the ‘old politics’ in the hands of the enarques –the products of the National School of Administration, although Sarkozy is merely a lawyer–. Inspired by Spain’s Podemos’s idea of the ‘ruling caste’ (la casta), Le Pen speaks of la clique in a carefully crafted language that is closer to street slang, denouncing the two-party system (or at least the coalitions) of the Fifth Republic and appealing, in her very populist style, to le peuple.

Marine Le Pen’s FN has not only collected the votes of the traditional French far right but also of working-class segments that previously voted for the Communist Party or even for the Socialists. She has reaped the most votes in the regions with the highest unemployment rates –such as Nord-Pas-de-Calais and Picardy and Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur–, in a country whose economy remains stalled after the crisis. While the Islamic State’s terrorist attacks in Paris may have reinforced the image of President François Hollande, given his sure-footed response, they have also given a boost to Le Pen, who even before had called for the return of frontiers and a stronger nationalism in Europe, and have hardened the discourse of not only Sarkozy’s Republicans, who have gained the most in the regional elections, but also of the Socialists who are currently in office.

The FN, despite its extremism, has now become a mainstream party. In reference to a study by Le Monde based on previous surveys, it has been said that the FN is the preferred option of the country’s youth. But that is at best a half-truth: 35% of young people aged 18 to 24 intending to vote would do so for the FN, and 28% among those aged 25 to 34, well ahead of Hollande’s Socialists and Sarkozy’s Republicans. But those who intend to vote account for only 35% of these two age groups. If all left-wing options are added together, the FN equals them in the first age group but lags far behind among the second (at 44%, with the right at 26%).

It may come to pass that Le Pen is second in the French presidential elections in 2017, as her father was against Jacques Chirac in 2002 –with less than 17% of the vote–. At that time many voters decided to switch to the latter in the second round, further alienating many people from politics. Similarly, if Marine Le Pen gets through to the second round in 2017 she is unlikely to win against a single candidate –whether Republican or Socialist–. But it can rightly be said that her xenophobic, anti-Muslim and anti-European discourse can taint others. In fact, it already has.

These events are not so surprising, but they are certainly worrying.