Although the title of this comment suggests something different, the Strategic Review focuses on the defence and armed forces of France, and not on the country’s national security. As pointed out when the first White Book was published in 2008 with the extended title including both national defence and security, the defence dimension took priority over the non-military aspects of security. Although both Nicolas Sarkozy and Ségolène Royal announced during their election campaigns that they would concern themselves with national security, in line with the general trend in Europe at the time, the White Book on the National Defence and Security of France was very similar to the previous strategic review. Even the very few mentions of domestic security, diplomacy or civil protection were diluted in the version of the White Book in 2013; but they have practically disappeared in this last edition of 2017. From such omissions, and upon a close reading of the document, one could conclude that, in terms of France’s national security, la Défense et les Armées en sont le tout (‘defence and the armed forces are everything’).

“The sequence followed –strategy first, budget later– reveals the primacy of military power in France”

The Review was ordered by President Emmanuel Macron to be undertaken by the Minister of Defence, Florence Parly, and it was meant to serve as a basis for a future Law of Military Programming 2019-25. It was prepared in a record time of three months. The sequence followed –strategy first, budget later– reveals the primacy of military power in France. Instead of adjusting strategies and forcing structures to the budget available (as small and medium power must do), the French President has decided to try and maintain France among the great powers. It will not be cheap, as the defence budget would need to rise from €32 billion in 2018 to €50 million in 2025, if the budget is to reach 2% of GDP by then, a goal established in the Strategic Review. Such an investment is being justified by growing insecurity and by the economic and social dividends it would generate. However, it is actually being undertaken because France has a President with both vision and the will to lead, along with a national security culture that supports him.

The Strategic Review identifies how and for what such budgets should be used for. The money should be spent to provide the French armed forces with the means needed to carry out the missions to which they are assigned. These are precisely the means which have been skimped upon in the budgets of recent years and that were again cut in 2017, prompting the resignation of the previous Chief of the Defence Staff, Pierre de Villiers. The objective is also very clear: to preserve and even to augment the strategic, technological and operational autonomy of France, as Minister Parly declared to Le Monde (13/X/2017). The Strategic Review is a coherent document: but more cannot be done with less, and it is up to the political and military leadership to recognise this inconsistency and to correct it.

Autonomy is the most repeated word found in the Review; it is a concept that carried forward the Gaullist tradition of reserving final decisions for France. The Review places emphasis on autonomy because it recognises that France cannot depend on a multilateralism which is languishing in the face of proliferating challenges and threats. This situation obliges France, on the one hand, to reinforce its capacities to act unilaterally or in coalition with other partners sharing its global vision, and, on the other hand, to strengthen the development of the collective capacities of the EU and NATO, which would provide an additional complement to France’s strategic autonomy. France preaches and leads by example: it puts more money into the defence budget, invests more in technology and capacities, and widens its operational ambitions because it aspires to mobilise the will of partners and allies to share both challenges and opportunities. Mobilisation is pragmatic in that France supports any kind of cooperation that helps its national defence and security, regardless of the form it takes: bilateral, European, Atlantic, sub-regional, cluster or ad hoc.

“The French armed forces will operate and cooperate with those others with whom France coincides in terms of interests and inter-operability, and always so long as it complements French operational autonomy”

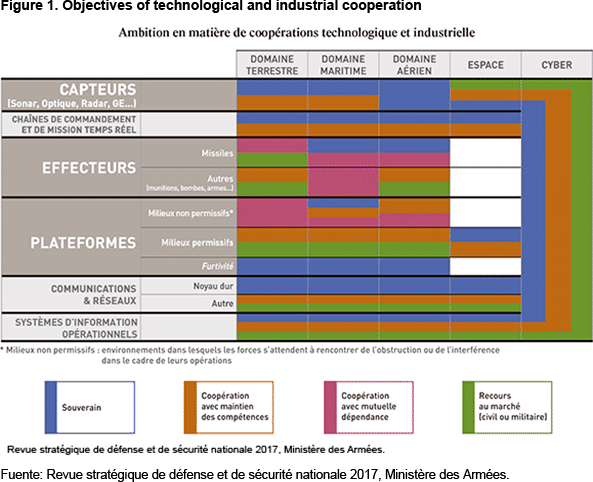

The 2017 Strategic Review has pointed to some important changes in the industry. In contrast to the 2013 White Book’s broader focus on the defence and security industries, the latest review emphasises the technological and industrial base of defence. This change is more than mere semantics and highlights how the defence industry has reached into all areas of security and defence. This State-controlled industry is the pillar of French strategic autonomy and the driving force of its national industry. The Strategic Review considers this industrial base to be essential for French sovereignty and therefore establishes very clear criteria for its future development. No one can expect France to share technologies critical to its defence industry and that are considered essential for maintaining its strategic autonomy. One could expect France to cooperate with others, however, as long as it does not put its sovereignty at risk or generate a mutual dependence. France would preferably seek cooperation within a European framework, but it does not rule out other associations beyond Europe, and even to enter the commercial market, as shown in Figure 1.

Similar criteria guide French cooperation in the operational sphere. France wants to have armed forces that can undertake as wide a spectrum as possible of missions and that possess the highest possible level of operational capacities. The country aspires to preserve its autonomy in the domains of intelligence, territorial protection, military operations, other security and cybersecurity operations, and in the realm of special asymmetric missions and missions of influence. The French do not rule out the possibility of receiving contributions from third parties to complement their autonomy, but they do not want to depend on them to undertake operations because they do not trust the slowness and complexity inherent in the resulting decision-making process. This explains their interest in implanting agile decision-making procedures within the permanent structured cooperation of the EU and their willingness to put to the test the solidarity of cooperative partners in the face of decisions taken. The French armed forces will operate and cooperate with those others with whom France coincides in terms of interests and inter-operability, and always so long as it complements French operational autonomy. In this sense, France will lead any bi/mini/multilateral configuration of forces as long as it has been articulated beneath its own planning control, mustering of forces, operational command and control, and inter-operability.

Now that it has been published, the Strategic Review still faces the inherent difficulties involved in transforming the Review’s lines of orientation into specific policies. France will have to confront controversial issues –from deficit and debt levels to the inevitable delays and lags which mediate between desired goals and action and execution– but one cannot deny the merit and valour of recognising reality and trying to change it. France shows a will to enable strategic transformation, and that should cause us a salutary envy.