On 14 October the European Commission made public its selection of the first set of Projects of Common Interest (PCIs) regarding Europe’s energy infrastructure.[1] The 248 PCIs selected are supposedly intended to increase the integration of the EU’s energy networks and markets, solving the isolation of some Member States, promoting the integration of renewable energies in the EU’s energy mix and diversifying gas imports by opening up new gas corridors. There is no surprise in the fact that Commissioner Oettinger has once again missed the opportunity to address the serious shortcomings that afflict European energy integration. The most remarkable aspect in the Communication is how short-sighted the European Commission’s long-term energy vision for Europe looks.

This is especially so as regards the lack of answers to Spain’s long-lasting demand for increased interconnections with France, although similar criticism can be levelled at the scarcity of common projects with neighbouring countries, the absence of projects that facilitate the integration of renewable energies and the neglect of smart grids, which are widely perceived to be among the most promising energy-related technologies. The Communication recognises its shortcomings in an almost pre-emptive manner, stating that ‘much more still needs to be done’, that this first list of PCIs is ‘just the first step towards the implementation of the longer term infrastructure vision’ and that the list ‘will be reviewed every two years with a view to integrating new projects’.

The absences are more significant than the projects included. For instance, it only selects two smart-grid projects –a technology that is expected to shape electricity markets in the years to come–, few projects address the troubled energy interdependency between Mediterranean Europe and its southern neighbours –apart from the Galsi Pipeline connecting Algeria to Italy (Sardinia) and some vague references to the Israel-Cyprus–Greece gas interconnector, also known as the Euro Asia Interconnector– and there are no significant common projects intended to facilitate the integration of North African renewable resources into the EU’s energy space. Including the need to secure supplies from North Africa and using energy infrastructure as a way to advance functional integration and energy-based development in such a disturbed region would have required an excessively long-term strategic vision. Despite the failure of Commissioner Oettinger’s beloved Nabucco project, its downgraded substitute still receives the bulk of attention as a gas diversification driver, even if supplies beyond Azerbaijan are more than dubious.

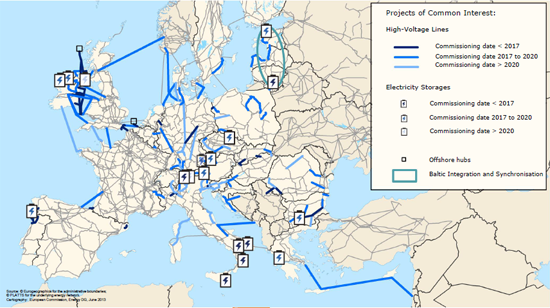

The Communication was frostily received in Spain. A simple look at the energy infrastructure maps provided by the Commission show a profusion of interconnectors, pipelines, grids and storage facilities in Northern and Eastern Europe. In contrast, the map of Spain is almost empty, with only six PCIs of minor significance compared with the evident lack of interconnections that the country has been denouncing for years with no significant solution being offered by the Commission.

The Barcelona European Council in 2002 agreed on a 10% electricity-interconnection target over installed production capacity , but the communication warns that Spain will not reach that target with the selected PCIs, being the only Member State to remain well under the 10% target after its implementation. The Communication recognises that ‘still more projects need to be identified for the true integration of the Iberian Peninsula within the European market’. In fact, Spain appears in a prominent manner only under the heading of ‘remaining challenges’, which symptomatically accounts for more than half of the Communication’s text (four out of seven pages). The first ‘remaining priority’ (an extraordinary expression that reveals the nature of an EU energy policy that is plagued with ever-lasting ‘remaining priorities’) in electricity is to ‘[f]urther increase the interconnection level between the Iberian peninsula and the rest of the continent’.

As for gas, the Commission states that the ‘gas system must further increase flexibility…, including through the development of more LNG terminals’. However, there is no recognition of the contribution that existing Spanish LNG facilities (already operating well below capacity) could make to flexibility and gas diversification, a much easier and cheaper strategy than embarking on uncertain initiatives like the Southern Gas Corridor to the Caspian. There is no recognition either of the potential for gas diversification that North Africa can offer to non-Mediterranean Europe, and no vision on how to profit from the two existing gas pipelines running from Algeria to Spain to open a functioning North-South Western gas corridor rather than embarking on wishful thinking about the Caspian Sea.

To be fair, it should be recognised that the Spanish government does not seem to have been able to put forward any far-reaching projects that are easy to accept by the Commission, or more importantly for that matter, by France. It is also understandable that the French government does not want to deal with another pack of renewable-electricity providers at negative prices like those from Germany. But this lack of proposals also applies to (third) neighbouring countries. For instance, the absence of any common project with Morocco in the field of renewable energy shows to what extent the blocking of the Mediterranean Solar Plan is related to the Spanish renewable energy market’s current distress. However, this is at least as short-sighted as the Commission’s vision, because were Morocco to join the Energy Community Treaty it could benefit from virtual green exports (on the basis of green certificates) with no relaying grid from Morocco to the EU’s markets.

Some observers have also suggested that the few proposals submitted by Spain are explained by the reluctance of certain Spanish companies to export renewable electricity to France at low, or eventually even negative, prices.[2] But in the final analysis, this is the result of a dysfunctional European energy policy, whose integration model is far from efficient or conducive to the competitiveness of European firms. National priorities shape the debate, but some more so than others. The Spanish energy sector is highly diversified by geographical origin and energy source, and Spaniards have paid a high cost in developing a competitive renewable energy sector following the EU’s sustainability narrative. However, neither Spain nor the EU can benefit from these efforts in an inconceivable negative-sum game for a true energy integration project.

This matches the more general criticism on the lack of consistency of a kind of melting-pot of national rather than European priorities, or on the disproportionate emphasis on electricity and gas without any link to the EU’s allegedly environmental and climate-change priorities. The message delivered by the Commission is a lack of coherence and leadership, as well as a feeling that it is incapable of addressing the many weak links that plague the EU’s energy infrastructure. The next Commissioner will undoubtedly have to face this fundamental weakness in the EU’s energy policy, but in order to do so he or she will need a longer-term energy vision that really deserves the name.

[1] Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions (2013), ‘Long term infrastructure vision for Europe and beyond’, Brussels, 14.10.2013, COM(2013) 711 final.

[2] L. Doncel (2013), ‘España queda al margen de las grandes obras de energía europeas’, El País, digital edition, 20/X/2013.