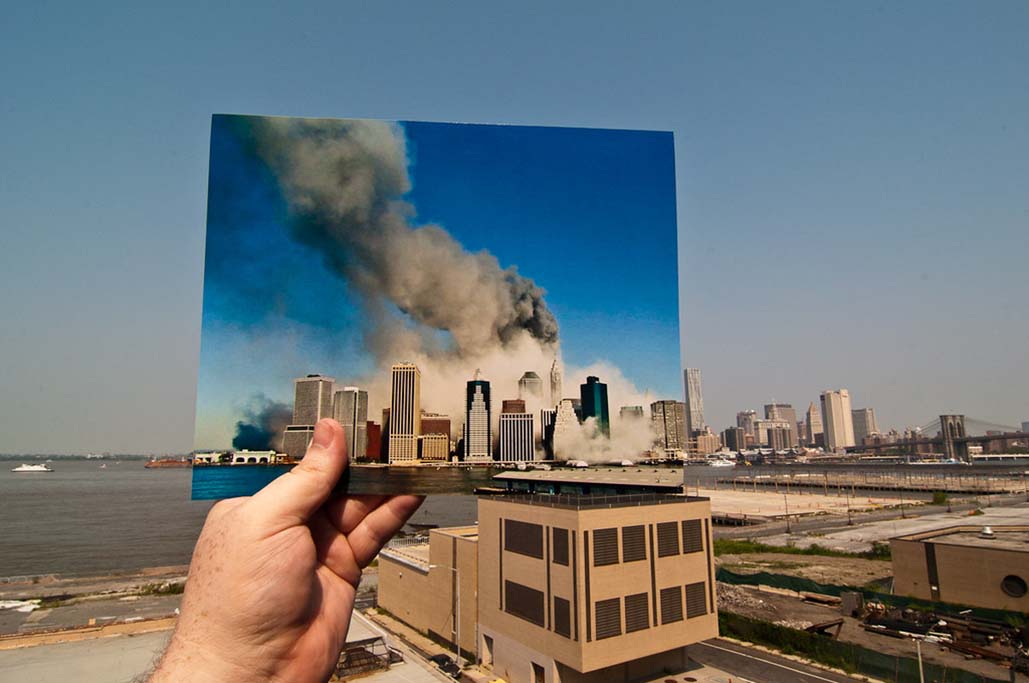

George W. Bush, Bush junior, entered the White House in January 2001 on a platform that emphasised a degree of isolationism, deriving from the unipolar episode the US was experiencing. The September 11 attacks that same year awoke him from the slumbers of the strategic snooze the US (and the West) had been lulled into and unleashed –egged on by the influential Neoconservatives in his Administration– a new era of US interventionism geared towards changing various regimes, such as Afghanistan under the Taliban and Iraq under Saddam Hussein and ‘remaking the Middle East’. We have witnessed the results. Their reaction sprang from the fact that they ‘overestimated the effectiveness of military power to bring about fundamental political change’, as the political scientist Francis Fukuyama has argued. Obama began the withdrawal from Iraq, and Trump announced the pull-out from Afghanistan, aware of the disillusion among voters. Twenty years after the attacks and the subsequent invasion of Afghanistan starting on 7 October that year, the current US President, Joe Biden, has brought this long Afghan war to a close, ‘ending an era of major military operations to remake other countries’. It marks the end, at least for now (is it a sea change or a pause?), of interventionism, of nation-building and of the construction of states along more liberal lines.

It involves not only Afghanistan, nor only the US. Even Pope Francis (although he does not represent the West) agrees with the (still) German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, in viewing as ‘irresponsible’ the policy of ‘intervening from the outside and building democracy in other countries, ignoring the traditions of the people’. The West is pulling back from a certain type of operation as a means of defending interests, exporting freedoms and even its understanding of democracy, when this is at the point of a bayonet (or its modern equivalent). Twenty years down the line less importance is placed on the fight against Jihadist terrorism, as opposed to cyber and space defence and technological rivalries in general.

As well as leaving Afghanistan, the US is reducing its presence in Iraq even further, a place where it triggered so many disastrous events, principally the birth of Daesh, otherwise known as Islamic State. In July the US agreed the end of its military operations there in order to focus on the training and logistics of the Iraqi armed forces. Trump had already withdrawn the bulk of US troops from Somalia. France too is in retreat from Mali and in general from the Sahel. Last June Emmanuel Macron declared that French forces in the Sahel would not remain there ‘eternally’ (having arrived in 2013). For now they will be reorganising. As The Economist points out, they are not withdrawals from a position of success, but of failure. This is without mentioning Yemen and Libya. Will there be an ‘Afghanistan syndrome’, as there was in the case of Vietnam, but this time with a Western and not merely US scope?

It is a mistake to engage in military operations or wars with no plan for how to emerge from them, because the withdrawal ends up as a debacle, as witnessed in Afghanistan. But there are other reasons and causes underlying these Western retreats. First, the fight against terrorism and insurgencies has proved extremely expensive. In the war and reconstruction of Afghanistan alone the US has spent more than US$2 trillion and the Europeans US$20.3 billion. Other priorities are now coming to the fore, such as competition with China in a range of areas, and, to a lesser extent, with Russia. There is also the confidence of being able to attack or counterattack terrorist groups remotely, with drones or cruise missiles, without involving troops on the ground, barring limited special forces for surgical strikes. Moreover, the US believes that the ‘war on terror’ has been successful, first and foremost for the US itself, which has avoided any new attacks on its own territory and has regionalised terrorist groups outside the West. While continuing to cooperate on intelligence matters, Europe needs to seek a way to extricate itself. Nation building in a liberal sense, which smacks heavily of ideological neocolonialism, has proved a failure both for cultural reasons and because the plundering of prodigious sums of money has led to local corruption. The desired outcomes have not materialised, because the premises and instruments were faulty.

It is not a total retreat. The US continues to maintain a network of facilities, bases and military deployments in the world that is quite unequalled by any other power. But the withdrawal may affect the world order. The US is very often a factor that lends stability, although at other times it is destabilising. It needs to think out its foreign policy better, and not only on the basis of its polarised domestic politics. NATO meanwhile needs to reflect on its future with more realism, all the more so when many European diplomats in Washington are suffering grave misgivings, first with Trump and now with the manner in which the withdrawal from Afghanistan was handled, rather than because of the intrinsic importance of the country itself, which has been the graveyard of so many empires. This is the first time NATO has used Article 5 (regarding collective defence) of its founding treaty in a major operation and it has resulted in failure following the unilateral decision of the US. It has been more of a political and social defeat than a military one. NATO had found a new reason for being in Afghanistan, while reviving the traditional opposition to the caprices of Putin’s Russia. On the question of China, where there is no unanimity, it will not find a new purpose. Meanwhile, awareness of the fact that Europe, the EU, needs to equip itself with strategic autonomy, as the High Representative Josep Borrell has pointed out, has increased among European governments, although the full consensus and resources needed for this are still lacking. There is a lack of strategic vision, which must focus on Africa as much as the East.

Does this Western retreat leave a vacuum? Not necessarily. Of greater concern than the one China and Russia may fill, with other instruments, in Afghanistan and its neighbours, the vacuum has been laid bare in the lack of global governance in this crisis and others, stemming from multiple causes. Both the UN and the G20 (but also NATO and the EU) have been found wanting. It is this, rather than the partial withdrawal of the West, which, once again, has erred in its strategic planning, that should be the cause of concern.