Last December a major shift in the tectonic plates of climate governance occurred. Over 190 countries were able to agree a ground breaking new global agreement on climate change in Paris. A number of Latin American countries including Brazil, Mexico, Peru, Colombia and Chile, among others, were instrumental in ensuring a positive result.

Additionally, an alignment of scientific, economic, energy and governance variables helped secure the Paris Climate Agreement. The changes that have occurred, the role of Latin American countries during COP21, and the challenges and opportunities presented by the agreement were analysed at a roundtable in Madrid on the 14th of January.

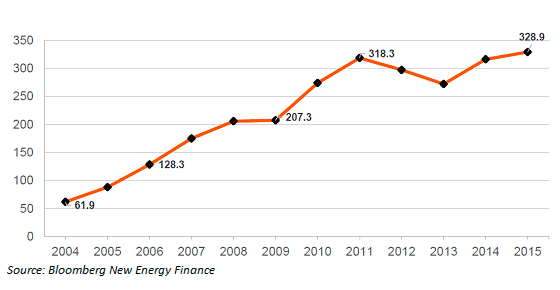

The meeting began with a brief analysis of the context in the build-up to Paris. This road has been paved, inter alia, with a better understanding of climate change as an unequivocal phenomenon, with a clear anthropogenic component and effects that are increasingly and asymmetrically being felt globally. The narrative regarding climate change economics has evolved. From the early days of the climate-policy ramp and the Stern Review’s call for prompt and decisive action the plea for climate action is increasingly being heard in economic circles. The global energy sector is slowly but inexorably embarking on a low carbon transition. In 2013, there was more renewable power capacity installed globally than fossil fuel power capacity and in 2015 clean energy attracted US$ 329 billion (see figure 1).

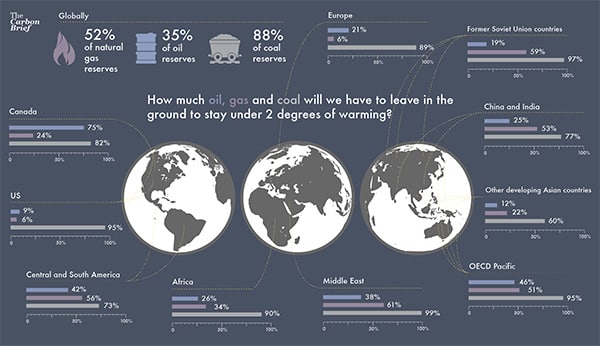

Achieving the ‘well below 2ºC’ temperature goal enshrined in the Paris Climate Agreement will entail leaving in the ground between a third and over 80% of fossil fuels, a realisation that can help push the energy transition forward (see figure 2).

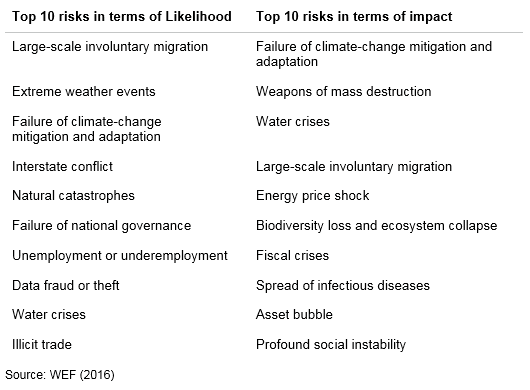

Climate risk is also increasingly present in investment portfolios, and features prominently in global risks analyses (see figure 3). Additionally, multilateral institutions including the World Bank, the IMF and meetings of the G-8 and G-20 have inserted climate change in their agendas.

Climate governance factors, with unprecedented subnational level engagement, increasing commitments by the business sector and NGO’s materialised in the Lima – Paris Action Agenda, aimed at catalysing climate action to increase the level of cooperation and support for a new agreement.

As the negotiations entered the final stage, an informal group dubbed the High Ambition Coalition emerged. Its agenda focused on setting a long-term goal on global warming that is in line with scientific advice, five-year review cycles for emission reduction pledges, and ensuring developed countries deliver the US$100 billion for climate finance per year from 2020. Many of these points are now in the Paris Climate Agreement. Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico participated in the meetings of the coalition and Brazil also joined it on the final official day of the conference.

Latin America is responsible for around 10% of global emissions, a figure close to that of the EU. Despite its status as a relatively low-emitter, the region’s emissions from energy, including from power generation and transport, are increasing quickly. Latin America has an important role in contributing to global efforts to reduce its emissions but the region’s INDCs (Indented Nationally Determined Contributions) submitted in 2015 are for the most part not in line with the global temperature goal in the Paris Climate Agreement. Therefore, countries should consider revising their INDCs and increasing the level of ambition.

The Paris Climate Agreement will enter into force once 55 countries covering 55% of global emissions have acceded to it. Some elements of the agreement are legally binding while others are not. The long term goals and the national reporting requirements are legally binding. National mitigation targets submitted as INDCs for the post-2020 period are not.

The Paris Climate Agreement provides the world with a bottom-up set of commitments that are nationally determined rather than internationally agreed. Parties will present their nationally determined contributions every five years. A common transparency framework and the requirement that future commitments should be more ambitious will guide the way forward, along with the commitment by developed countries that at least US$100 billion will flow to developing countries annually from 2020. Adaptation and capacity building have been reinforced, as has the technology framework. A peak in emissions should be reached as soon as possible, a balance in emissions and absorption by sinks is to be sought by the second half of the century and sinks should be preserved. Whether the Paris Climate Agreement is enough to ensure the global temperature is kept well below 2ºC remains to be seen. Implementation and increased ambition will determine the extent of our commitment to a low carbon future.

The agreement sends a strong signal that the world needs to make a rapid transition away from fossil fuels toward renewable energy as soon as possible. This type of climate action can be a catalyst for a better type of development. As Latin America is considered one of the great frontiers for clean energy investment, renewable energy should be prioritized as it has significant potential to create jobs and improve air quality.

Even though the new agreement will not enter into force until 2020, Latin America should continue to develop and implement its climate policies. Given the impressive potential to develop Latin America’s renewable energy sources and the need to electrify the region’s transport system, the EU can play an instrumental role, especially during this period of weaker Latin American growth.

Spanish cooperation with Latin America on climate change remains a high priority. This cooperation is channelled through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation (MAEC), the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID), the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness and the Iberoamerican Network of Climate Change Offices (RIOCC) via the Ministry of Agriculture, Food and the Environment, among others. Moving forward, the Spanish government will support the region to create tools to analyse GHG emissions and marginal abatement cost curves, develop regulatory frameworks, undertake stakeholder engagement, access climate finance and develop climate research programs.

Taking into account Latin American countries regard climate action and development as mutually beneficial goals, it is an opportune moment to deepen EU-Latin American cooperation on climate change.