Turkey held parliamentary elections on 7 June 2015. They could have been like any other election if Turkey’s first directly-elected President and former Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan had not decided to put the current regime to the test. His aim was to change the country’s parliamentary democracy into a presidential system, in addition to establishing an undemocratic minimum-10% threshold to gain seats in Parliament.

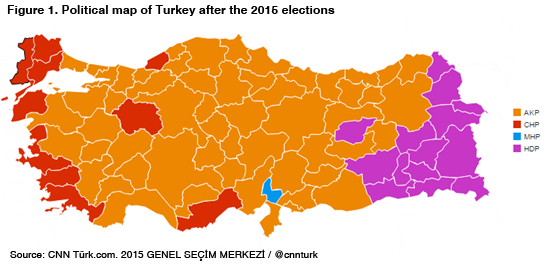

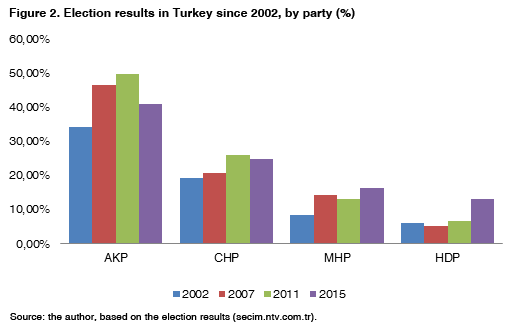

Turkey’s more than 47 million voters were called to the ballot box to elect 550 members to Parliament. The 86% turnout was very high compared with what is usual in most European countries. According to preliminary results, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) lost the majority it had commanded for the last 13 years. Nevertheless, it remained the most voted party, at 40.8%, and won 258 seats. The significant point is that Erdoğan will not have enough support in Parliament to change the Constitution and the regime, at least for the time being.

Turkey’s main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (CHP, responsible for establishing the Turkish Republic in 1923), gained 25% of the vote after an all-out election campaign by the party’s leader, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu. Contrary to previous elections, the CHP proactively determined the agenda to be discussed, set realistic goals and created economic policies instead of merely trying to answer back at the AKP’s accusations and responding in kind. Although the CHP was unable to increase its share of the vote, contrary to expectations, the shift from a reactive to proactive campaign is a happy development for the party’s future and raises hopes for the next elections.

The National Action Party (MHP) obtained 16% of the vote, placing itself in third place. It is ironic that both the Turkish nationalist party and the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) have the same number of seats, 80, in the new Turkish parliament. The party mostly relied on its long-standing position as ‘the’ opposition party and on the backlash vote against the HDP. Hence, it appears to have increased its percentage of the vote without exerting itself very much. Erdoğan played his cards, the HDP saw his bluff and the others were there for the ride.

The real winner: the HDP

The HDP, which decided to enter the elections as a party and not as a combination of independent candidates, is the elections’ real winner. It broke through Turkey’s 10% threshold and managed to obtain 13.1% of the vote. It was supported by more than 6 million voters, far beyond what its candidates had gained as independents in the previous election, in 2011.

“This is the first time since the 1980s that the ‘left’ has achieved such a successful outcome.2

The party has been accused of being the legal arm of the terrorist organisation Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). However, throughout the campaign, the HDP’s co-leader (the party has a man and a woman in each post, for purposes of gender equality) tried to explain its position to liberal and secular-minded voters in order to dispel the idea. Looking at the results, it would appear that he has been successful in expanding its identity from being merely a protector of minority Kurdish rights to being a champion of all oppressed social groups, including ethnic minorities, LGBT people and even women. The HDP’s efforts to be a ‘party of Turkey’ seem to be yielding the hoped-for results.

Nonetheless, many voters gave critically-needed support to HDP in order to exceed the 10% threshold and thus reduce the number of AKP-controlled seats and strengthen the opposition. The party’s leaders modestly admitted to this and explained that they were aware of the purpose of these votes that had been entrusted to them. They also said they would work hard to gain the hearts and minds of their voters over the next term and try to ensure they did not regret their decision.

This is the first time since the 1980s that the ‘left’ has achieved such a successful outcome. The CHP and the HDP together garnered 38% of the vote, which could be a sign that there is now a substantial social demand for change. The leader of Spain’s Podemos, Pablo Iglesias, congratulated the HDP through Twitter, claiming the three parties were connected ideologically. Naturally, Turkish dynamics are quite different from those in other European countries, although it could be said that the spirit inspiring the Gezi park social movements has had an impact on the election’s results, similarly to comparable mobilisations in other countries.

The election campaign

The election campaign was especially intense for two main reasons: the fight over the threshold and the activities of the President. Erdoğan had been the founder of the AKP but he campaigned on the party’s behalf despite it being strictly unconstitutional for the President to stray from a position of strict neutrality. The AKP not only counted on an extremely large budget but also on resources provided by the State thanks to the President’s involvement in promoting its cause. All others were in a position of inferiority, especially as regards use of the mass media.

Turkey’s civil society plays the game

It is important to underline the role played in the elections by the fear that they would not be free and fair. There was much concern about fraud, which in turn mobilised civil society. Voluntary organisations, numbering thousands of citizens, had been established to ‘protect’ ballot boxes. The largest voluntary organisation, ‘Vote and Beyond’, managed to mobilise 60,000 people in Turkey and cooperated with other organisations that aimed to secure votes abroad. More than 1 million Turkish citizens cast their vote in foreign countries and this increased the risk of election fraud.

An authentically new Parliament, and a much more colourful one

The Turkish parliament has 357 new members, with 193 having retained their seats. Thus, 65% of Parliament has been renewed. Female members now total 98 –30 of them from the HDP– and account for 17.8% of the total.

In addition to the positive development of the rising number of women in Parliament, ethnic diversity has also been enhanced. The first Roma candidate in Turkish history, Özcan Purçu, gained a seat in Parliament as a CHP MP for Izmir. In addition, three Armenians from three different parties were also elected, while an Assyrian lawyer, Erol Dora, became a member for the HDP. Furthermore, a Yazidi and former member of the European Parliament, Feleknas Uca, will represent her people along with Ali Atalan. This was another of the HDP’s pledges: opening Parliament to all ethnic groups and minorities.

“Whatever may occur, it is important for hope to be the winner in Turkey.”

What’s next?

Now is time to learn coalition-making. There are various options that can be summarised very simply but which in practice are very difficult to achieve. Any coalitions including the AKP –such as a grand AKP-CHP coalition, or AKP-MHP and AKP-HDP varieties– would have sufficient seats. The HDP has said that, according to its election pledge, any coalition with the AKP is out of the question. The MHP’s leader also ruled out the possibility on election night, even though it would have been a natural ally for the AKP’s Ahmet Davutoğlu. The CHP, on the other hand, has said it is open to discussion as Turkey should not be left without a viable government.

The other option is a coalition of opposition parties: CHP-MHP-HDP. This could also be an option, even if a recipe for difficult governance. As for the country’s economic situation, there are doubts about the efficacy of a three-party coalition.

The last option, which is as good as any other, is to call for elections again. If none of the political parties can establish a government, Turkey will go to the ballot box again in brief. This does not seem to be a good idea as the result might be a return to an AKP majority, based on the claim that the opposition is incapable of forming a credible government.

In conclusion, whatever may occur, it is important for hope to be the winner in Turkey. Turkish democracy has been under much pressure from authoritarianism for a long time. Freedom of expression, freedom of the press and confidence in the rule of law have all been in decline. Since the Gezi protests two years ago, public opinion has been seeking a way out. The 2015 election has provided the opportunity and a way ahead. There is still much work to do, but at least there is now an alternative.