A great revolution of recent decades has been the powerful emergence of a significant global middle class. Among the destructive effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, one of the greatest is its worldwide decline and the growth of those in poverty, except in China. According to a Pew Research Center report, after a decade of progress on both fronts the global middle class has shrunk by 54 million people relative to the forecasts for 2020, compounded by the reduction in the upper middle class and the wealthiest. And, far from recovering, it seems likely that their fortunes will stall. The country that has been hardest hit is India, accounting for 60% of this social reverse, having lost a third of its middle class (with a drop from 99 million to 66 million). But even developed economies have not been immune from the setback, which is likely to have sweeping social and political consequences, with a negative impact on global consumption and giving impetus to the rise of identity-based populist and authoritarian movements.

Let us start with the definitions employed by Pew, which are consistent with other international centres and organisations, the figures used in the research being based on World Bank data. They focus on daily and annual income, although other factors such as type of education, employment, housing and so on may also be used. Middle class means living on an income of US$10-20 a day, or US$14,600-29,200 per annum for a family of four. Upper middle class means US$20-50 a day. The highest incomes are at least US$50 a day. The poor are defined as those living on less than US$2 a day, or US$2,920 per annum for a family of four.

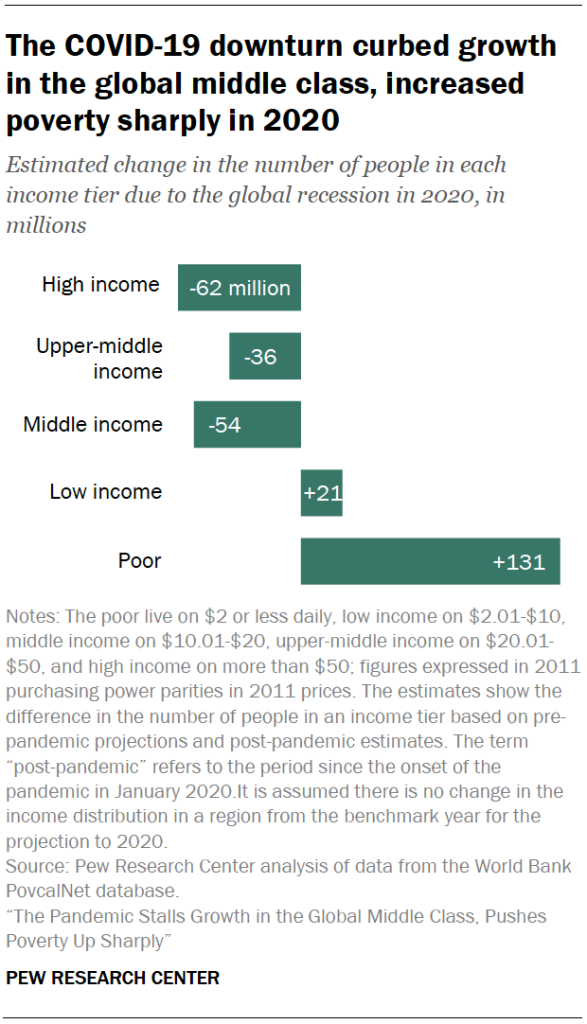

Prior to COVID-19 it was estimated that this global middle class, which is or was changing the world, had grown from 899 million to 1.38 billion between 2011 and 2019 (out of a global population of more than 7.7 billion). In 2020 (the figures will be greater now that the pandemic has extended into 2021) there were 54 million fewer people in this middle class, 36 million fewer among those on upper-middle incomes and 62 million fewer on high incomes. The vast majority of the wealthiest –489 million out of 593 million– live in developed economies and many of them are slipping down to lower rungs of the ladder, meaning that the true loss is even greater. The number of people classified as poor, after a decade of successfully reducing poverty, with some 49 million people escaping the situation every year, increased by 131 million in 2020 owing to the recession, climbing to 803 million, or 10.4%, South-East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa are particularly affected, whereas the forecasts predicted it would have fallen by 8.7% had it not been for the pandemic.

China is the only large economy that did not suffer a recession over the course of the last year, and in the first half of 2021 it is recording spectacular growth. Pew calculates that the number of middle-income Chinese has fallen by 10 million –there were already 504 million of them prior to the pandemic– and 30 million people have joined the ranks of those on low incomes (US$2-10 a day). The levels of poverty have not deteriorated. There are now more people in China among the middle and upper-middle classes than among the ranks of the poor and the lower-middle class. This may shed light on certain aspects of the Chinese regime’s assertive behaviour and its real level of support.

Bleakest of all is that the recovery prospects for the global middle class are not good. A report issued by the US National Intelligence Council, Global Trends 2040, based on the same data, suggests it is unlikely –it will depend on political and social dynamics– that the global middle class will be able to match the growth rate preceding the pandemic between now and the end of the next decade, given the slowdown in the growth of global productivity and the fact that the expansion of the working-age population is coming to an end demographically in overall terms.

According to the US report, the middle class is shrinking in the advanced economies, trapped between the growing segment of higher incomes and the smaller section that falls below the poverty threshold (this is once the pandemic is over, and despite the fact that the percentage of the population falling below the national poverty threshold in the advanced economies has risen in 19 of the 32 countries studied between 2007 and 2016, including France, Germany, Italy and Spain). It also suggests that the middle class in many countries will be hit by increases in the costs of housing, healthcare and education. There is a polarisation, in which the number of workers in low-income jobs and the number of people with high incomes grows simultaneously. This is what the economist Tyler Cowen (Average is Over, 2013) predicted when he referred to the hollowing out of the centre.

This polarisation may be aggravated by the automation of tasks implicit in the Fourth Industrial Revolution, as even the International Monetary Fund is now warning in its latest report on the global economy. A recent Lex column in the Financial Times, reflecting on the development of software capable of doing white-collar jobs, writing reports, drafting sports and economic news stories, and other advances, referred to the ‘the invisible march of the middle-class droids’. On the other hand, the phenomena of digitalisation and connectivity are serving to bring large sectors of developing countries’ populations into the banking system (often through Fin Techs), aiding their social progress and incorporation into the global middle class.

The National Intelligence Council report states that ‘large segments of the global population are becoming wary of institutions and governments that they see as unwilling or unable to address their needs. People are gravitating to familiar and like-minded groups for community and security, including ethnic, religious, and cultural identities as well as groupings around interests and causes, such as environmentalism’.

Even prior to the pandemic, Miguel Otero, Federico Steinberg and I had posited that a challenge for our times would be the avoidance of a global clash of the middle classes, between those on the wane in the developed economies and those they were preventing from ascending in the emerging economies. With the effects of the pandemic and other developments, these tectonic shifts may intensify and generate internal and external destabilisation.