Resource governance is a relatively novel issue in global and European energy governance. By the mid-1990s there was already an overwhelming literature on the ‘resource curse’ showing that the contingent benefits of oil, gas and mining for economic development were not being realised, leading instead to increased inequality and poverty. Furthermore, resource-rich countries were found to be more prone to conflict (internal and external) and corruption. The proposed solution was providing mechanisms to improve transparency in resource management and opening it up to scrutiny and dialogue with civil society. These ideas found a significant response within the development community during the late 1990s, not only among the World Bank and Western donors but also in civil society as a result of campaigns favouring company reporting such as Publish What You Pay (PWYP) in 2001. The growing activism of Global Witness, Human Rights Watch and Oxfam America was first felt in the US and later in certain European countries.

The PWYP campaign was particularly successful in the UK and the Blair government started to work on an initiative built on the notion of a joint reporting standard for governments and IOCs. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) was officially launched in London in June 2003 with a Statement of Principles to enhance the transparency of payments and revenues in the extractive sector. The US Congress gave a mandate to the Security Exchange Commission (SEC) to issue an extractive resources payment rule known as Section 1504, part of Dodd-Frank Act signed into law in 2010. Section 1504 requires that all oil, gas and mining companies listed in US stock exchanges engage in annual public reporting of any payments to foreign governments exceeding US$100,000. However, in July 2013 a US federal judge voided the SEC’s requirement in Section 1504 that US companies report competitive information that could be used against them by global competitors. In September 2015, a US Federal Court decision ordered the SEC to submit an ‘expedited schedule’ to issue a final ruling within 30 days.

This introduced some uncertainties that weakened the US’s leadership vis-à-vis the EU, with the latter enacting a more stringent regulation that encompassed more companies and sectors. The European Commission started to work on new disclosure legislation and a final rule was approved in June 2013 after a heated debate and strong pressure from energy lobbies and NGOs. It requires extractive companies to disclose payments over €100,000 to governments on a country-by-country and project-by-project basis, stipulating annual reporting, sanctions for non-compliance and applicability to non-European companies. It covers almost 3,000 companies, including Russia’s Gazprom. Member States can impose sanctions depending on national law and extending from naming and shaming to fines. The transposition period is almost closed, and member States must pass it into law before 2016. Starting from 2016 listed companies will have to publicly disclose all payments they make to governments of the countries in which they operate (Ernst & Young even has a nice brochure comparing EU and US norms).

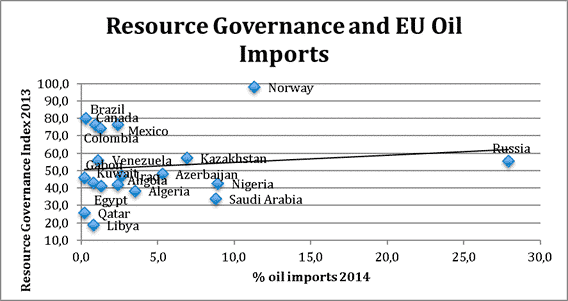

The shift from material (natural-resource reserves and production) to normative (regulating extraction) capabilities illustrates the vertical transition from hard to soft energy power and the role the EU seeks to play in producing norms as global public goods. Nevertheless, in 2014, the fact 1 is that –as Figure 1 shows– Europe continues to import oil from countries with a poor Energy Resource Governance Index (NRGI). Only 16% of European oil imports come from producers with a ‘satisfactory’ level of resource governance, ie, with NRGI scores of over 70, including Colombia, Mexico, Canada, Brazil and Norway, the latter alone fortunately comprising more than 11% of EU oil imports. In contrast, around 40% of oil imports are from ‘weak’ or ‘failing’ producers. ‘Weak’ resource-governance oil exporters have NRGI scores of between 50 and 40 and include Nigeria (9% of the EU’s oil imports), Azerbaijan (5%), Iraq, Angola and Kuwait. ‘Failed’ producers are those with NRGI scores of under 40, such as Qatar, Libya, Algeria and, more importantly, Saudi Arabia, which alone accounts for almost 9% of EU oil imports. The EU’s leading oil supplier is Russia, which ranks low –with a NRGI score of 56– in the ‘partial’ governance range but accounts for 28% of the Union’s oil imports. Kazakhstan is in a similar (mis)governance position and accounts for 7% of EU oil imports. Figure 1 above also shows the adjustment line, identifying which countries are above or below.

The question is: how much will the picture change once the EU’s new directives come into force? The new rules will be in place next year and the data will provide the answer, but no big surprises should be expected.

1 For further information, see Gonzalo Escribano & Enrique San Martín (2014), La Unión Europea y el buen gobierno de los recursos energéticos, Revista CIDOB d’Afers Internacionals, nr 108.