Today we are launching the 2020 edition of the Elcano Global Presence Index. This 11th edition does not yet reflect the effect of the pandemic, so, in a sense, it can be considered a description of the world before the eruption of the pandemic. A world that had, however, already undergone a remarkable transformation since the 2008 crisis.

The pandemic has also changed the research agenda of this project. The biennial global presence reports, in which we present the main results of the Index as well as the trends in the globalisation process, have been put on hold, replaced by biannual analyses that try to anticipate the impact of the pandemic on the globalisation process.

We continue, however, with our annual data release, while maintaining the addition of 10 new countries to our database with each new edition. It is now the turn of Armenia, Benin, Brunei, Chad, Guinea, Moldova, Mongolia, Niger, Papua New Guinea, and the Republic of Congo. Therefore, we offer global presence results for 140 countries, since 1990, in an open access database covering 99% of the world’s GDP and 97% of its population.

And, with each new edition we incorporate improvements in the index methodology, which are applied to the entire historical series since 1990. This year we have conducted a new international survey for the weighting of the different indicators and dimensions that make up the Index.

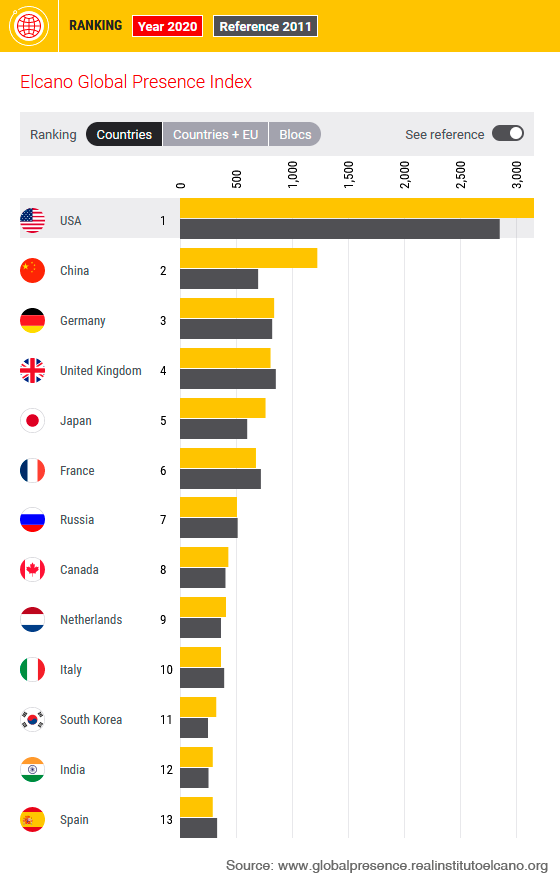

2020 Ranking: Asia unstoppable, Europe still suffering from the Great Recession

In this new edition there are significant changes in the ranking of global presence, even among its top positions, which is unusual for an Index that is fundamentally conceived to report on structural changes. This reflects the fact that we are at a time of historic change.

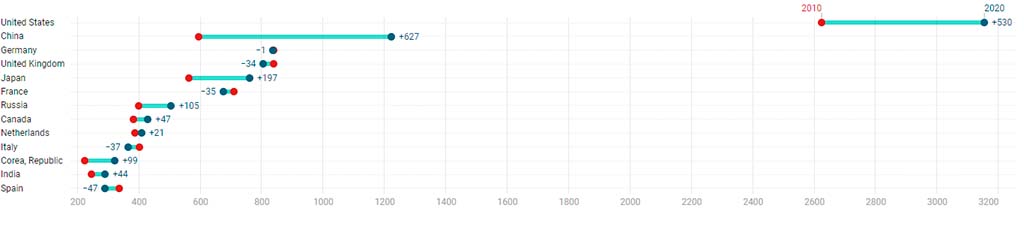

The US still leads the world ranking, followed by China, but the gap continues to narrow. Between 2019 and 2020, US global presence grew by 2.1% compared to China’s 4.5%. The gap is still considerable, with the US presence being 2.5 times that of China. However, in 2010 US external projection was more than 4 times higher – in 1990 more than 12 times -. Moreover, China already leads the Index ranking in manufacturing, information and, for the first time in the series, science. Also, both countries have by far the largest increases in global presence in the last decade, while the decline of the European powers is materialising.

Germany and the UK remain in 3rd and 4th place respectively, but with different trends. Germany has accumulated two consecutive years of loss of global presence -both economic and military and soft-, while the UK has maintained mild increases. However, its distance from 5th-placed Japan is narrowing, while the latter is experiencing a notable recovery in the rate of growth of its external projection.

In fact, Japan is, after China and the US, the country that records the largest increases in presence between 2010 and 2020. After the long crisis of the 1990s, Japan’s external projection declined in the face of the rise of other Asian countries, with the consequent loss of its regional leadership. But in recent years it has regained dynamism in both its economic presence – through foreign investment and crowding-out manufacturing exports – and its soft presence – pushed by the technology indicator.

France and Italy, 6th and 10th in the global presence ranking, respectively, follow the European trend of global presence losses, while Russia, Canada and the Netherlands do register external projection growths. The Netherlands is one of the few exceptions to the general decline in the global presence of European countries, something closely related to the country’s external orientation and the evolution of foreign investment due to its fiscal particularities. Most EU countries have not recovered their pre-Great Recession levels of global presence, due to the reconfiguration of the integration space in the aftermath of the crisis, with a weakening of intra-European links. However, the EU’s presence in the rest of the world – that is, member countries’ extra-European ties – has increased, partly in response to such weakening of the common space, although this increase is insufficient to compensate for the previous loss or to prevent the sustained rise of Asia.

South Korea has held on to the 11th place since 2014 – a position previously held by Spain – although in recent years it has been registering absolute reductions in its index value, mainly due to the economic dimension. Perhaps Asia’s export strategy was already showing signs of exhaustion before the pandemic.

Spain drops another place, which is gained by India. Spain is now 13th, although its foreign projection continues to grow in index value, sustained by its soft projection. In 2020, Spain has not yet recovered its 2010 level of global presence, neither economically nor militarily, although it has recovered its soft presence. Spain’s external projection profile in this pre-pandemic edition has more weight in services and less in investment abroad, is less militarised – both due to the reduction of troops abroad and less military equipment – and is softer – with more weight in tourism, but also in technology, science, and education, and less in development cooperation.

India is recovering the growth of its global presence, although it still ranks relatively low compared to its size in terms of GDP (6th in the world ranking) and compared to its size in terms of population (2nd place). This is explained by India’s development model which, unlike China’s, has been inward-oriented, although there appears to be a reversal of this trend. India has recorded significant growth in economic presence – with a greater role for services, followed by manufacturing – as well as in some indicators of the soft dimension – culture, science, and technology.

In short, over the last decade, Asia has boomed, Europe has slumped –with a few exceptions –while North America has kept the pace.

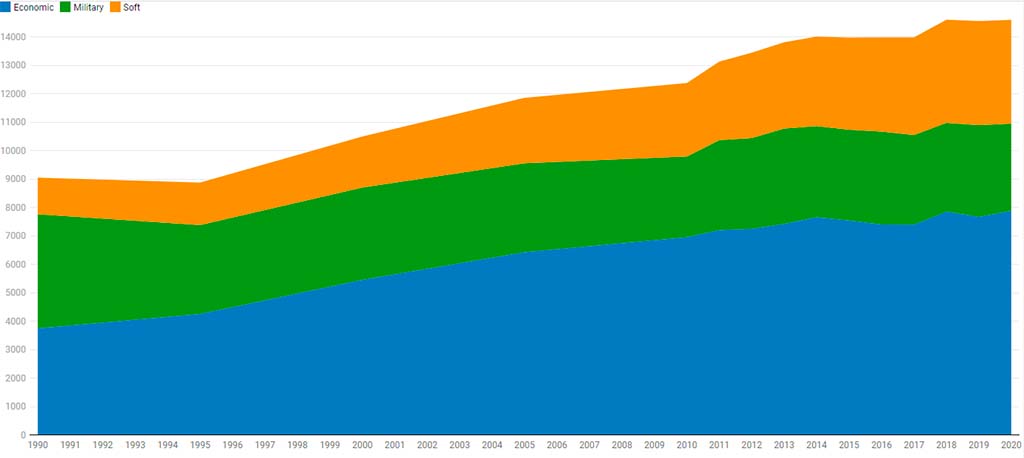

Stagnant globalisation

Considering the Elcano Global Presence Index as a possible measure of the globalisation process, we can observe a slight recovery of the process between 2019 and 2020. Even so, the aggregate growth rate in the last decade has been remarkably low, when compared to what happened in previous decades. The globalisation process has plateaued, as the greater dynamism of the soft dimension cannot compensate for the economic contraction. In other words, Europe’s decline is not being compensated for by greater integration in other regions or by the uprising of new emerging countries. The pandemic has therefore impacted on a trend that had been brewing before its outbreak.