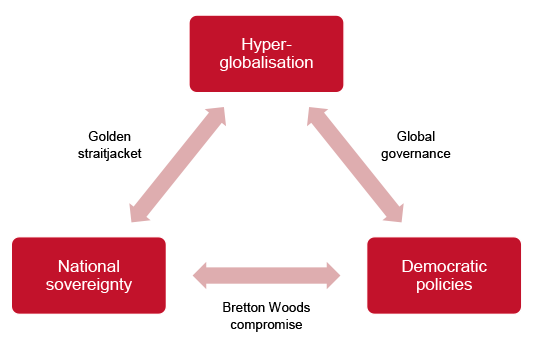

In his book The Globalization Paradox, published in 2011, the Harvard Professor Dani Rodrik formulated his famous trilemma: it is impossible to attain economic hyperglobalisation, national sovereignty and democracy simultaneously, because only two of these things can be achieved at any one time. The sides of the triangle must be chosen (and it is a choice that comes with consequences: global governance, a golden straightjacket or the Bretton Woods compromise, also known as the liberal order). But at a time of emergence from a lengthy crisis and a change of the world order, the three vertices –and therefore the sides– are all fracturing at once, or at least being subjected to tensions they may or may not be able to withstand, certainly in Europe but also further afield: globalisation, which was already stalling and more so now with the trade war unleashed by Trump; national sovereignty, with the territorial tensions in a range of states and the new nationalisms; and democracy, with reverses to the rule of law in various places, the crisis of systems and the rise of populist movements. A choice can no longer be made between the three sides.

Let us start with national sovereignty, although paradoxically it may prove to be an illusion in these times, at least for European societies. Various countries are being subject to territorial tensions, to secessionist movements or serious internal division. Spain is one of them, with the Catalan question as well as other less obvious centrifugal processes. But we are also witnessing the way Italy is politically, socially and economically cleaving into two, between north and south, albeit managing to stay united for now, in an unstable way, through a governing coalition of two populist movements with different leanings and territorial strongholds. There are many other cases, witness for example Germany with Bavaria. The national sovereignty issue is fuelling nationalism, at both the state and sub-state levels. Nationalism and pro-sovereignty movements have been bolstered in such major countries as Russia, Turkey, China, India and the US (‘America First’).

These tensions around national sovereignty are affecting European integration, which used to be a sui generis response to Rodrik’s trilemma, but is now in delicate health, weakened by the divisive forces mentioned above. In turn, the EU used to have its own trilemma: it could not strive simultaneously for closer integration, the maintenance of the nation state and democracy. Macron has started an interesting debate about ‘European sovereignty’.

As far as democracy is concerned, as the Freedom House and The Economist indices both indicate, it is in retreat throughout the world. Authoritarian regimes (of various stripes) are not only not waning, if anything they are becoming stronger. China is the clearest example. Even in Europe, supposedly the home of democratic values, there are clear democratic reversals, for instance in Poland and Hungary, member states but at the same time pro-sovereignty and radically opposed to accepting more refugees and immigrants, an attitude that is spreading like an oil slick with a corrosive effect on the EU. In many cases the populism that supports nationalism and restricts globalisation has blossomed. What has happened in both European (France, Spain, Germany, Italy, etc) and non-European democracies has led to the destruction or profound transformation of the existing systems of political parties.

Globalisation has faltered. UNCTAD’s most recent World Investment Report shows a 23% reduction in the world’s flows of foreign direct investment in 2017. While the World Trade Organisation states that the growth in trade in 2017 was the greatest since 2011, it also reports that between October 2017 and May 2018 the restrictive trade practices of the G20 economies doubled compared to the same period a year ago. And this was when the Trump Administration’s tariff war had not even got going. The economist Paul Krugman claims that a widespread trade war could cut world trade by 70%.

A key problem is that not only can Rodrik’s trilemma not be broken down into pairs, but that what has happened in the triangle’s three vertices and sides has generated a vicious –not virtuous– circle that affects everyone. A good deal has been written on the subject. The relationship between the defence of sovereignty and democracy has already been touched on in this blog; likewise, the relationships between globalisation and national identity, and the former and the loss of democratic controls. These are causal relationships, not mere correlations.

The British political scientist David Held sees another kind of triangular crisis, connected to the preceding one, in which the crises of democracy, of globalisation and of global governance all overlap, producing a state of gridlock that threatens the former world order, the principles of democracy and global cooperation. According to Held, the institutions (what others call the ‘liberal order’, the base of Rodrik’s triangle) of the post-war world enabled interdependence to grow as new countries joined the global economy, a virtuous circle that could not last because ‘it set in motion trends that ultimately undermined its effectiveness’. Now multipolarity, the assertions of sovereignty by the great powers and the decline of the West make it more difficult to arrive at agreements on global governance, when the problems are more complex, ‘penetrating deep’ into domestic politics, including the conflict generated by those who are left behind in societies. For Held, the gridlock ‘freezes’ problem-solving capacity in global politics, whether the problems be commercial or geopolitical in nature, as is evident in parts of the Near East and elsewhere, something that in turn unleashes waves of refugees who affect the domestic politics of recipient countries.

In other words, to express it in Rodrik’s terms: the vicious circle that is being generated in the vertices and sides of the trilemma hinder a way out. It is not that it has become catastrophic, yet, but it is certainly worrying, at the very least. And it requires, if not solutions, then at least options. To be continued.