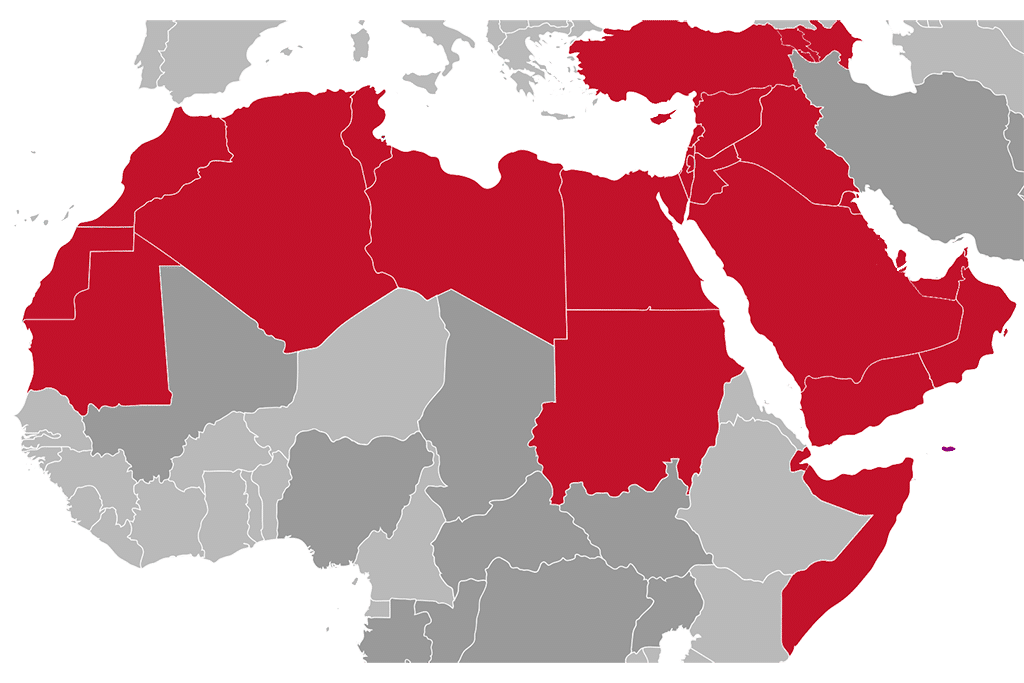

In the context of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, access to cyberspace by states and societies poses risks to security across systems, services and infrastructure. Despite measurable progress in this regard, that is to say, in securing both undisturbed access to and use of the cyberspace, the regional states share a particular trend of prioritizing capability development in the face of a different threat: political and social destabilization. Similarly, the need to draw on cyber defence against state-perpetrated or sponsored aggressions is frequently overshadowed by the proclivity to rely on active defence, interlacing with the geopolitical rivalries partitioning the region.

Every MENA country –Algeria’s passivity depicting the most atypical case–, later than sooner, has hosted international events, established legal and policy frameworks, designated institutional structures and greased its informational machinery in order to signal its commitment to shield cyberspace. Nonetheless, that shell finds itself subtly displaced by practices and initiatives pursuing the control over it –a sort of cyber control–, in line with an understanding of the World Wide Web that gives preference to the concept of ‘cyber sovereignty’. The main focus seems to sideline threats to IT infrastructure and services in a cyber connected context in favour of those threats to the model of political stability and social peace defined by the regimes, which implies the search for control over information flows, often with ramifications beyond territorial borders.

Cyber control

State cyber espionage on critics and activists, or on suspects thereof, under pretexts that blur the difference between political motivation and national security, leaves behind a wide palette of cases. In Egypt, where the 2018 cybercrime law compels internet-service providers to store user data for its hypothetical request by security agencies, monitoring and intrusion systems have been used on non-governmental organizations’ employees as well as vocal critics abroad. Moroccan Hirak leaders were victims of ‘enhanced social engineering messages’ during the latest peak of protests: basically, phishing attacks intended to install spy software in their mobile phones. It is not unusual within these kind of operations to target individuals from different backgrounds and for dissimilar reasons. Therefore, the goals of social control and yielding a relative advantage over geopolitical adversaries may appear together. For instance, two Twitter employees were indicted for allegedly accessing user accounts of Saudi and other nationalities after being recruited by the government. This has turned out to be the first-ever formal accusation against the Kingdom for espionage in the US.

In MENA, we equally spot private firms offering cyber espionage and cybersurveillance services leaving quite a noisy trace throughout the region, such as the Israel-based NSO or Black Cube. In an unprecedented move, Facebook has sued the former on the basis of selling spyware and handing operational support to track journalists, dissidents and human rights defenders. The case is said to implicate 20 different states, with UAE and Bahrain among them. By the same token, the great powers have made their own contributions to the cause: former US National Security Agency (NSA) and White House officials advised the UAE in its actions against Qatar as well as in those pursuing social control, representing another example of how a cyber offensive instrument may serve divergent purposes. For its part, Russia’s SORM (System for Operative Investigative Activities) has several MENA customers, namely Iraq, Bahrain, Qatar, etc. SORM allows communications interception and surveillance inside a given country. Meanwhile, China is trading key components for Dubai’s initiative Police Without Policemen, which attempts to revolutionize our understanding of urban surveillance.

Influence operations embody another course of action in line with social manipulation and control ends. A hectic activity in social media combines intimidatory measures with the deployment of ‘bot armies’ that harass or bury unfavourable opinions and swell partisan messages. To those aspects already addressed, it is also relevant to add the ability to restrain or even shut down internet’s traffic as seen in Iraq and Iran -in the latter, with unprecedented success- amid the new cycles of mass protests. According to Netblocks, connectivity reached to minimums of 22% and 5% respectively, while the protests had garnered high momentum by the end of the year.

Cyber offensive

Among the tools available in cyberspace, the MENA countries have not ruled out the use of the offensive ones against third states, given their lower cost and greater deterrence capacity compared to defensive instruments, at least from the urging perspective of boasting retaliatory options.

Council on Foreign Relations’ Cyber Operations Tracker shows that Iran or hacker groups somehow related to the state, between July 2012 and January 2019, conducted 16 cyber espionage operations comprising multiple attacks targeting interests in MENA, especially those located in Israel and Saudi Arabia -the actual number is presumably much higher, indeed, but it is still representative of the general modus operandi. A macro-conspiracy involving Qatar was uncovered last year, affecting approximately 1.400 people. Following a spear-phishing pattern, the operation aimed to get access to football players and religious figures’ email accounts as well as more straightforward rivals like Bahrain’s crown prince. Actors with lesser international outreach, such as Lebanon, are also joining these activities: an apparent mistake made by the main intelligence agency led to the online discovery of content where there was “literally all kind of stuff”.

Although cyber defence offensive instruments delivering disruption or interference continue to excel among the capabilities of Israel and Iran, more MENA states are gradually signalling more sophisticated cyberattacks. The most visible –and critical in geopolitical terms– example so far is the Emirati operation that enabled the diplomatic and economic offensive against Qatar by the so-called Quartet –Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, UAE and Egypt– two years ago: the defacement that linked emir Tamim al-Thani to comments in support of Hamas and Iran. It did not take long before a good number of emails from the Emirati ambassador to the US were leaked to the press, most likely by pro-Qatari agents, thus representing a retaliatory action in the form of a hack-and-leak operation.

Gregory Gause’s core argument in his book on the international relations of the Gulf seems to retain some validity: Middle Eastern and North African states’ approach to cyberthreats prioritizes those drivers of political and social instability at home over those threats on information systems and networks. Regarding the cyber-defence dimension, to attack or counterattack are preferred avenues to the struggle to defend, in the classic sense of the term. An aggressive stance toward cyberspace prevails in numerous instances, and what is left for us is to see whether time will continue on this path or if we will witness a redefinition of priorities in the future.