The Trump Administration’s announcement of import duties on steel and aluminium may trigger a spiral that leads to a trade war. In themselves, the measures are not of great importance. But they are important in terms of what they could signify. The announcement is based not on a whim, but on three ploys: (1) he links it to national security; (2) he uses it as a means of extorting partners and allies for other ends; and (3) it may enable him to take definitive ownership of the Republican Party agenda. Trump is trying to deliver on what he promised in the 2016 campaign, which many did not take seriously.

The bogus pretext of national security: the Trump Administration has appealed to national security as the justification for the tariffs, citing section 232 of a 1962 trade act passed in the middle of the Cold War. The World Trade Organisation (WTO) explicitly allows trade restrictions based on national security, but they have hardly ever been invoked. Doing so makes it extremely difficult to appeal to the WTO, because it is highly unlikely to want to enter into exactly what constitutes national security. It is a way of thwarting the WTO, which is not an organisation of free trade but of trade rules (it has succeeded in getting China to modify some of its practices, for example). It is quite clear that Trump’s measures have little to do with national security. According to Pentagon data, the steel and aluminium needs of the US military account for less than 3% of national output.

There has been a certain alliance between this Administration’s trade and national security apparatuses. The Secretary of Defense, Jim Mattis, and the National Security Advisor, General H.R. McMaster, are obsessed about the race with China for technological supremacy. The announcement and the obsession could be closely linked, although as far as steel and aluminium are concerned China is not one of the countries most affected by the new measures. Rex Tillerson’s abrupt departure from the State Department and his replacement by Mike Pompeo, former Director of the CIA, together with the resignation of the President’s Economic Advisor, Gary Cohn, replaced by Larry Kudlow (a free-trade supporter but reportedly able to live with these protectionist proposals), strengthens the protectionist ‘America First’ brigade that the Trade Representative, after Trump himself, embodies like no other.

The White House has wielded national security to play politics, and to undermine the WTO. It has an ever more prominent role in the trade policy of the Trump Administration, and that of other countries. Citing national security considerations of this type the President has vetoed (before it was announced) the purchase of Qualcomm, a maker of semiconductors (among other things), by Broadcom (based in Singapore). The Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS) is becoming increasingly active. This trend in security is also evident in Europe, amid the possibility of technology companies being bought by Chinese capital. While not in the realm of security, the announcement that 10% of shares in Daimler (the maker of Mercedes Benz) have been bought by the Chinese firm Geely has sent shock waves through Berlin.

The extortion ploy: Trump has suspended the measures in the case of Canada and Mexico, on condition that they reach an agreement to amend the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) as he wants. The Europeans are also waiting to see whether they are going to get special treatment from the US as partners and allies; if not, it would lead to reprisals and a possible escalation (Trump has had his sights on imports of high-end German cars for some time). Another possibility is for Washington to differentiate between European states (which would be unacceptable, because it would be in contravention of the EU’s trade unity) or make other demands. According to Politico, Lighthizer told the European trade commissioner, Cecilia Malmström, that the EU would be made exempt from the measures if the it showed itself more dependable and active in the fight against over-capacity (ie, against China) and other initiatives.

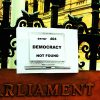

A power play for the Republican Party and its agenda: protectionism was part of Trump’s DNA long before he reached the White House, but not the Republican Party’s, which adhered more to a free-trade stance. The Party and many of its think tanks were opposed, but Trump is taking over the party. As Fareed Zakaria points out, ‘Trump is more in line with his party’s base than most of its leaders’. He quotes a poll that suggests support for free trade among Republican voters has fallen 21% in a decade, while among Democrats it has risen 14%: a complete reversal of traditional affinities. And it also comes at a time when the executive has been wresting power from the legislative branch (Congress) on trade matters.

All this seems rather behind the times considering that the economy is shifting towards new products, to global value chains, artificial intelligence and the economy of intangibles. These days the global flows of data contribute more to worldwide growth than the trade in goods, as a report on the transatlantic digital economy points out. Japan meanwhile has managed to resuscitate the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), abandoned by the US under Trump, and now going by the name of Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). Of course, the EU’s response to Trump could be to restart talks on the moribund TTIP, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership.

Trump tweeted that ‘Trade wars are good, and easy to win’. A year earlier, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, the Chinese President Xi Jinping had said that ‘Nobody can win a trade war’.