Due to the authoritarian nature of his regime (a format now known as ‘illiberal democracy’, since he actually wins elections), to the way he annexed Crimea and intervened in the Eastern Ukraine, to his homophobia and other similar traits, Vladimir Putin is the object of widespread distaste in the West (although he does have some fans among the growing European far right). But it must be recognised that without Russian military intervention in Syria things would not have begun to move and there would be little hope of a glimmer of pacification on the horizon. Putin’s Russia has not acted on humanitarian grounds but in defence of bare-faced power interests, such as gaining a friend in the Middle East, an area where it had lost ground and that is being redrawn, and an important base in the Mediterranean. It also has security considerations in mind, since attempting to de-activate the Islamic State (ISIS or Daesh) is also a priority for the Russians.

The US Administration has understood this well. But not so the Europeans, who still believe that they have some influence in the area. Telephone communication between Washington and Moscow is alive and well. The Foreign Ministers of both the US, John Kerry, and the Russian Federation, Sergei Lavrov, have already spoken face to face in Vienna, at the meeting held to discuss Syria. They agreed to invite Iran –finally, as it is a key player without which peace will never be reached– to the talks. And it was a success that the two great rivals, not only in Syria but throughout the region, Iran and Saudi Arabia, were seated at the same table. Furthermore, in a very sensible move, the Russian and US military are in contact with each other and have manoeuvred together, not to coordinate their action but at least to prevent accidents during each other’s bombing runs.

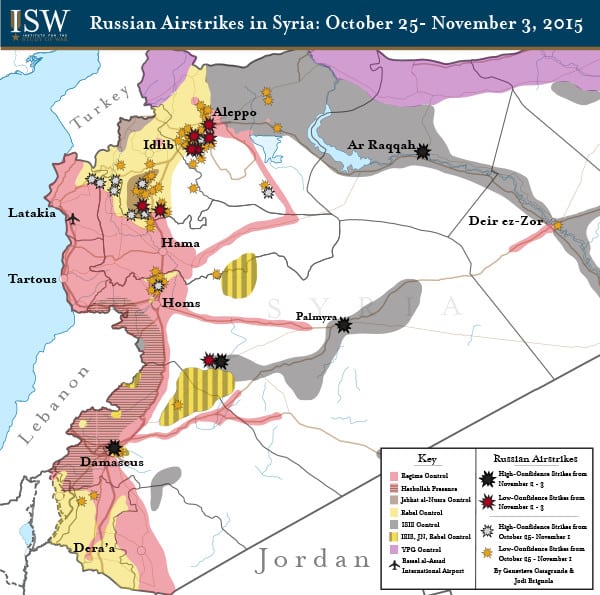

It is quite true that Russia is not just bombarding Daesh’s positions but also the facilities of rebel groups fighting the Assad regime –a highly diverse complex of groups, including elements from al-Qaeda–, and Russia has declared it has reached agreements with some of them and is still in negotiations with others. Some may congratulate themselves that Russia has got itself stuck in a quagmire from which it will only emerge bruised and battered (and what might have been bomb exploding on a Russian airliner over Sinai may well be a warning sign). But Obama, who was becoming increasingly disengaged from the drama in Syria, has had to reconsider, given Russia’s active role and the refugee crisis that is fostering right-wing extremism in Europe. He has already decided to dispatch a special operations group, numbering around 50 effectives, which is not much but at least a beginning. Will it become inevitable to have boots on the ground?

Many, both in Europe and the US, have become convinced that demanding Assad’s removal –despite being backed by Iran, although more the actual regime than the individual himself– is now not only not a priority, given the emergence of Daesh, but that it could also be counterproductive if it were to lead to chaos. The lessons of Iraq and Libya are clear: a regime, or a state, should not be destroyed without creating another one in its place, either beforehand or in the process of ousting its predecessor. There is talk of partitioning Syria, which is the situation it is already in –divided between areas controlled by the regime, the various rebels and Daesh–, but it is important to maintain, as in Iraq, the fiction of a single state, with its borders intact, while attempts at designing some sort of transition are in progress.

Russian action and the influx of Syrians refugees into Europe has finally awoken NATO to the reality that the threat is not only in the East –which some, but not all, identify as neoimperial Russia– but from the South, where the real risk is a situation of chaos on which terrorism can feed and grow. Next month NATO is to present a Southern Strategy, among other things to ‘project stability’ without necessarily having to deploy conventional military forces, according to its Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg. NATO, nevertheless, using language now obsolete, continues to speak of its ‘Southern flank’. However, it is no longer a flank but a front, liquid perhaps but in a physical sense and as defined by Zygmunt Bauman.

In Syria, and by extension its entire surrounding area, the US and Russia are moving jointly to draw up a diplomatic plan, despite their underlying great-power rivalry. Might Kerry and Lavrov become the new Sykes-Picot of the Middle East, as noted by Spain’s former Foreign Minister Miguel Ángel Moratinos? It is unlikely. Neither the US nor Russia have the capacity to impose a solution, should there be one and, even if there is, it is unlikely to be good but perhaps only less unsatisfactory. Nevertheless, at least they can do something, which the Europeans have proved incapable of. Europeans are always reluctant to talk about ‘interests’ because they prefer to take comfort in ‘values’, that meanwhile they are themselves forgetting to put into practice.