The Spanish economy is now firmly out of recession and jobs are beginning to be created, particularly in the services sector, but the stubbornly high unemployment rate will not dip below 20% until 2017, according to the government’s forecasts.

Spain has two measures of unemployment, which makes for a confusing picture. The stated rate is based on a quarterly survey of households and the registered rate reflects those recorded in the government’s employment offices as jobless and actively looking for work (job seekers) at the end of each month.

The stated rate was 25.9% at the end of March (5.9 million people and almost a quarter of all those unemployed in the 28-country EU), while the number of registered jobless was 4.7 million at the end of April (a rate of 23.9%).

The substantial 1.2 million difference in absolute terms between the two figures is due to various factors. The higher stated figure includes people who say they want to work but who are not registered as jobless because they do not think it worthwhile, they are not really interested in working or wish to avoid controls as they are working in the black economy. The registered figure is regarded as closer to reality.

There are, however, some encouraging signs from both measures. The destruction of jobs in the first quarter (184,600) was the smallest decline in this period since 2008, The first quarter, moreover, is traditionally a bad one for employment, including before the onset of the crisis in 2008. Meanwhile, the number of registered unemployed fell by 111,565, the largest fall for April since existing records began in 2011.

The number of people affiliated to the social security system in April was 16.43 million, 133,765 more than in March and 197,701 more than April 2013.

These figures led Mariano Rajoy, the Prime Minister, to say he was ‘hopeful about the future because I think we have broken a trend of destruction of employment and we are already heading in the opposite direction’.

More than half the rise in social security affiliation in April was due to the hotel and catering trade (69,725). Tourism employed 1.32 million people that month, the fourth-largest provider of jobs after commerce and vehicle repairs (2.91 million), manufacturing (1.81 million) and health (1.13 million). Tourism is enjoying another bumper year.

With the economy officially forecast to expand 1.2% this year and 1.8% in 2015, the government estimates 600,000 jobs will be created over the next two years. The labour market reforms approved in 2012, which lowered firing costs and enable companies to opt out of sector-wide collective bargaining agreements depending on their financial health, have reduced the GDP growth threshold for net job creation from around 2% to 1.3%, according to labour-market experts.

When the property bubble burst in 2008 jobs were destroyed as quickly as they had been created. Between 2002 and 2007, the total number of jobholders, many of them on temporary contracts, rose by a massive 4.1 million, a much steeper rise than in any other EU country and more than three times higher than the number created in the preceding 16 years. Since 2008, more than 3 million jobs have been lost, around half of them in the construction and related sectors. As construction is a labour-intensive sector, its collapse had a huge knock-on impact throughout the economy.

There are now 1.9 million households where all members are unemployed, and the number of long-term unemployed (more than one year) is 3.65 million (61.6% of the total stated jobless). This is particularly negative as the longer someone is unemployed, the less likely they are to find a job.

The problem for Spain is that there is no other sector that can create the number of jobs that the construction and property sectors managed to do, albeit temporarily, apart from tourism to a much lesser extent, and that sector, while flourishing, has expansion limits and many of its jobs are seasonal. The export sector is also booming, but it is not particularly labour intensive, and the need for a more knowledge-based economy is hampered by the inadequate education system.

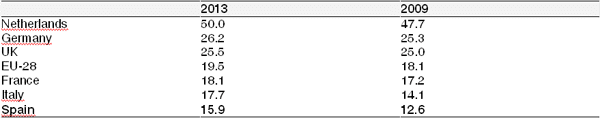

The crisis has wrought structural changes in employment. The share of total workers on temporary contracts dropped from 34.1% in 2006 to 23.4% last year, while those with part-time jobs increased from 12.6% to 15.9% between 2009 and 2013 (see Figure 1 below). Both figures, however, are far from the EU averages. Temporary workers were the first to lose their jobs as of 2008, particularly in the construction and related sectors, while more people are taking on part-time jobs to make ends meet and thanks to reforms last December that made rules on these jobs more attractive for employers. The latter is an important change: many part-timers go from being subsidy receivers to tax payers.

Spain faces a long haul in reducing the unemployment rate to the low of 8% before the crisis, and even that was still high by US and UK standards.