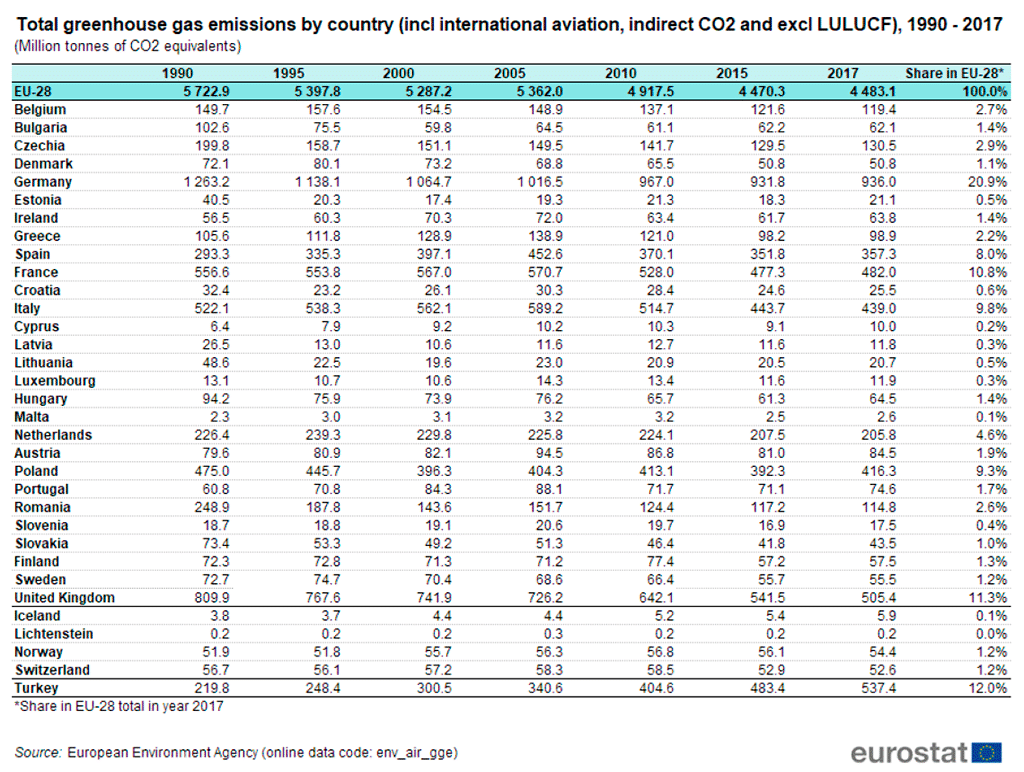

Spain is both a climate hot spot and one of the largest GHG emitters in the EU-28 (see table 1). It does not yet have a framework Climate Change and Energy Transition Law, despite its commitment at COP21 in Paris back in 2015. Acceptance of such a law by citizens is paramount to its success. However, knowledge regarding support for a framework climate law is limited. In order to support the analysis prior to the adoption of said law the Elcano Royal Institute carried out a survey to understand citizens’ concern regarding climate change and their support for different elements, instruments and processes that could be included in Spain’s future Climate Change and Energy Transition Law. This survey builds on Elcano’s previous work on legislating for a low carbon transition, in liaison with the Grantham Research Institute of the London School of Economics. The most salient results from the survey can be summarised as follows.

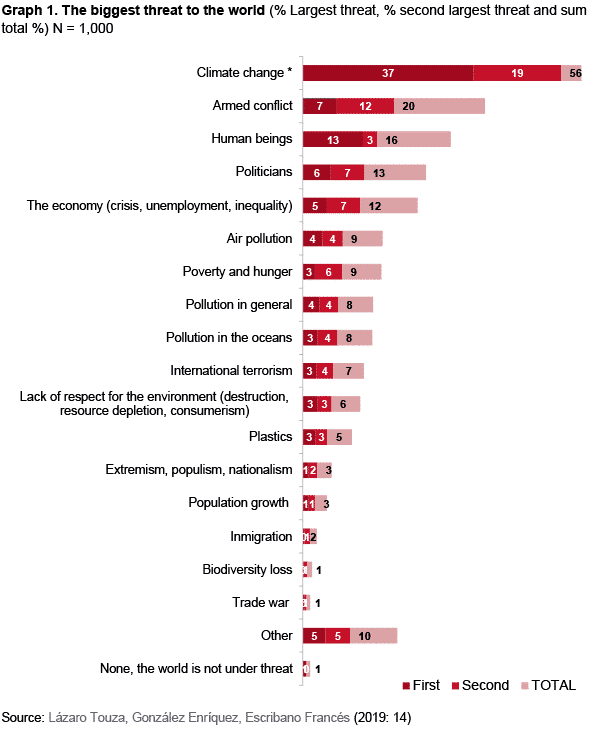

Spanish citizens perceive climate change as the biggest threat to the world2 (see graph 1 below). As regards Spanish citizens’ ecological world-view, measured on Dunlap’s revised New Ecological Paradigm scale of 1 (low pro-ecological worldview) to 5 (high pro-ecological worldview), the average of the sampled population is 3.69, which is similar to other Western and developed countries. As for the effect of socioeconomic and ideological variables on respondents’ views, the score on the NEP scale increases with education and decreases as we move to the right on the ideological spectrum.

Regarding knowledge about climate change, there are very few climate deniers in Spain. Only 3% of respondents stated climate change does not exist. Similarly, there is broad agreement on the anthropogenic nature of climate change among respondents. Additionally, only 15% of interviewees believe that the impacts of climate change are not yet noticeable. Overall, the vast majority of respondents understand the basic ideas related to the science of climate change as established by the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report (AR5).

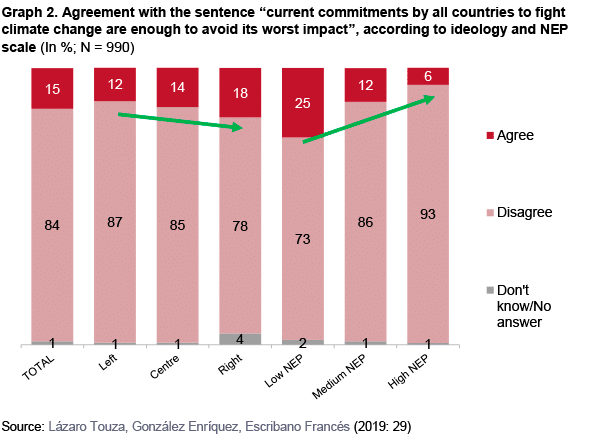

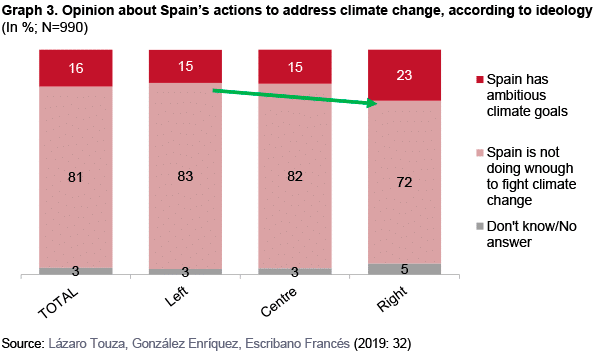

There is also a very broad agreement on the lack of adequate action to fight climate change both at the international level, and at a national level, with over 80% of the interviewees deeming it insufficient (see graphs 2 and 3 below).

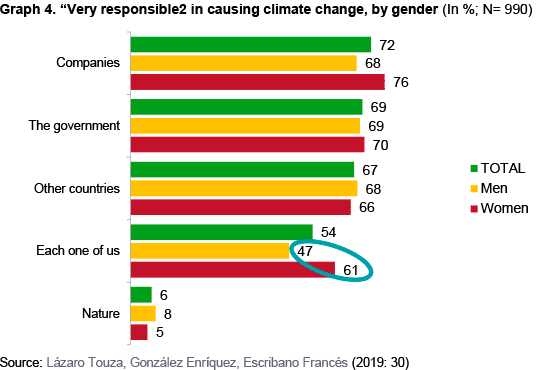

Companies, the government and other countries are perceived as highly responsible for climate change while there is more limited acknowledgement of respondents’ own responsibility for causing climate change. It is interesting that women acknowledge their own responsibility more than men (see graph 4 below).

One of the novelties of the survey is including citizen’s attitudes towards compensation for damages caused by climate change, i.e. testing preferences for public action beyond adaptation. Over 90% of Spaniards say they agree that the State should invest part of its budget in compensating for the effects of climate change. As expected, lower income respondents (income < €600 a month), interviewees on the right of the ideological spectrum and those with lower pro-ecological world view (low NEP score) are more likely to object to the State compensating for the damages caused by climate change.

Interviewees were asked whether they were willing to pay to prevent climate change. Respondents were informed about the weight of emissions from the transport sector in Spain’s global emissions. They were then asked whether they owned a vehicle and, if so, whether they would be willing to pay higher taxes in their annual road tax to mitigate climate change. Over 40% of respondents who owned a vehicle, even those with higher pro-ecological world view (high NEP score), were unwilling to pay more to limit climate change, showing limited personal involvement. On average (arithmetic mean calculated by using the mid-point of the payment interval offered to interviewees) vehicle owners who said they would be willing to pay agreed to an annual road tax increase of €46. Again, as expected, there is a positive relationship between both the level of income and the level of educational attainment of interviewees and the additional amount they would be willing to pay.

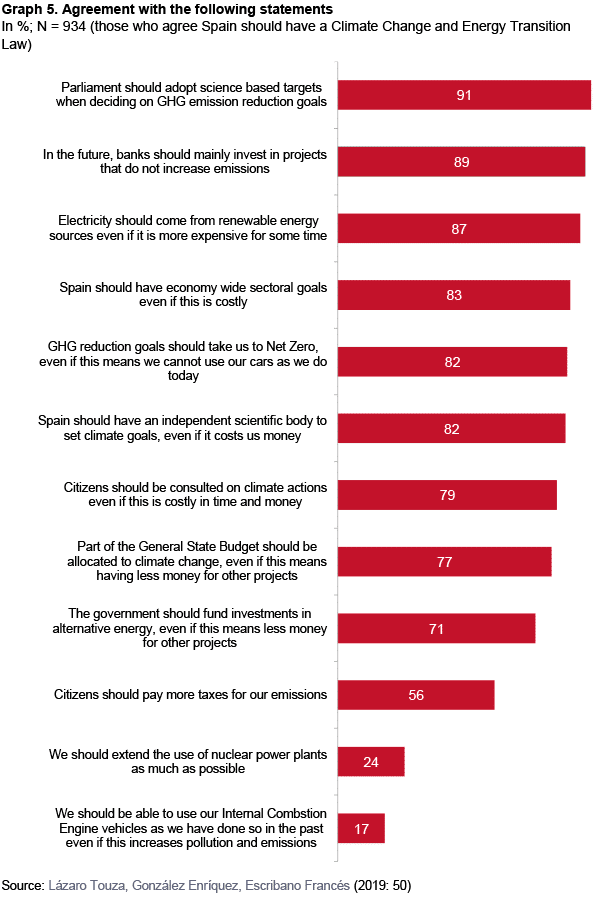

The vast majority of respondents (93%) believe that Spain should have a climate law. Overall, there is broad support for the key elements in Elcano’s prior case study analysis of robust climate laws worldwide. The vast majority of respondents support both the existence of an independent scientific committee that would suggest climate targets and the government adopting the climate targets put forward by scientists. Similarly, there is widespread support for a net zero target. To the question of whether citizens should be consulted on the measures to be taken to curb climate change most respondents answered they would like to participate in these consultations, although the percentage of respondents who want to participate in public consultations is lower among those with higher education.

More women than men respondents are against reducing the funds allocated to other purposes in order to fight climate change. Similarly, lower income earners, pensioners, and the unemployed would be less supportive of allocating part of the State budget to climate action compared with students or employees. Besides that, it is generally agreed that banks should invest primarily in projects that do not increase emissions. Only 17% of respondents agree that Internal Combustion Engine Vehicles (ICEs) can continue to be used as they have been so far. As regards nuclear energy less than a quarter of the sample supports extending the lifespan of nuclear power plants (see graph 5 below).

The survey suggests that socio-demographic and ideological variables play a relevant role in the attitudes of Spanish citizens towards climate change and the environment. Those more willing to fight against climate change are mostly the young, the well-educated, left wing respondents, and those living in large cities. However, in general, pro-environmental positions and concern about climate change are present across all socio-demographic and ideological groups, showing strong support for a Climate Change and Energy Transition Law and for the key elements of other countries’ robust climate laws: an independent advisory body setting emission reduction objectives, the adoption of said objectives by politicians, the inclusion of a net zero emissions goal, the cost of climate change being internalised, compensating the damages to which we will not be able to adapt and changing the way we move. Future studies could replicate this survey and expand this analysis to include citizen support for the new European Climate Law announced by Ursula von der Leyen.

For a more detailed analysis and more data, see “Los españoles ante el cambio climático”.

1 LULUCF is the acronym for Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry.

2 An open question (i.e. with no suggested answers) was posed to interviewees regarding top threats to the world.