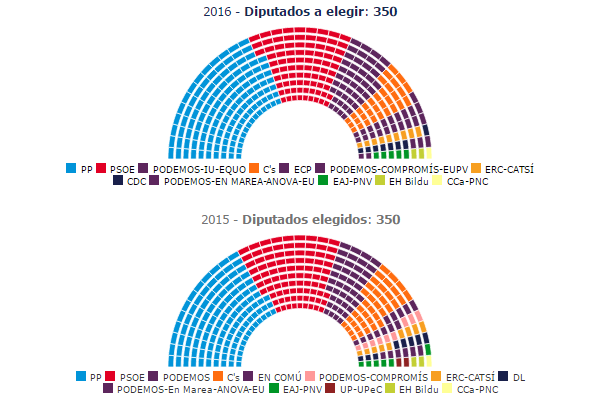

The Popular Party (PP) defied expectations and won more seats in the repeat election, but still far from an absolute majority, while Unidos Podemos (UP), the new radical left-wing alliance, failed to overtake the centre-left Socialists as polls had widely predicted. Parliament, however, remained as fragmented as after last December’s inconclusive election.

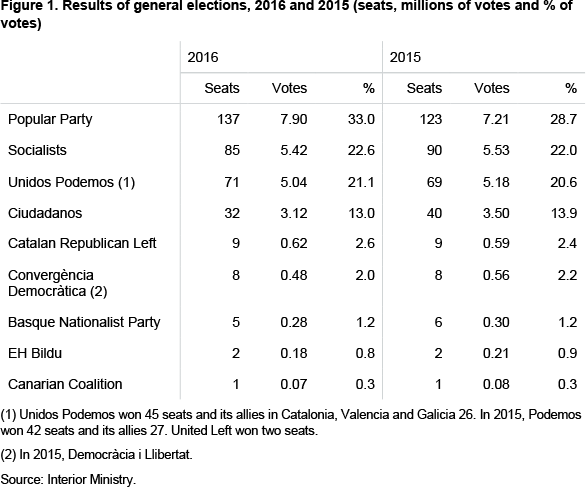

The PP captured 137 seats, up from 123, the Socialists 85 (its worst result ever), down from 90, Unidos Podemos (Together We Can), forged in May between the anti-establishment Podemos and United Left (the revamped communist party), won the same number of seats (71) as these two parties gained separately last December and the centrist Ciudadanos (C’s) 32, eight fewer (see Figure 1). By running on the same ticket, Podemos and United Left had expected to benefit from the d’Hondt system of proportional representation.

The PP’s results put Mariano Rajoy, the acting Prime Minister, in a stronger position to lead a new government, but he faces the same obstacles as before in his bid to form a coalition that has an absolute majority (176 seats). The Socialists refused to back or join a government led by the PP, widely tainted by corruption scandals, unless Rajoy stepped down. Having won close to 700,000 more votes (33% of the total) despite the corruption cases, Rajoy is unlikely to throw in the towel.

C’s had agreed a pact with the Socialists’ leader Pedro Sánchez, but this did not garner enough support in parliament. This time round these two parties have fewer seats between them (117 as against 130), 20 fewer than the PP’s 137 and making it unlikely that the pact would be resurrected. Ideologically C’s are not that distant from the PP, but their leader Albert Rivera would have to eat his words to form a minority government with Rajoy.

“Podemos and Ciudadanos have not managed to make further inroads into the political establishment”

Equally, UP and the Socialists (156 seats) do not have the absolute majority or very close to it forecast by polls. The Socialists are licking their wounds because of their worst-ever result, including winning fewer seats in their fiefdom of Andalusia than the PP for the first time, but do not have to face the humiliation of being pushed into third place by UP as they remain the dominant party on the left. Had UP overtaken them, the Socialists would have faced an agonising dilemma: forming a government with UP as the minority partner, which they showed no signs of wanting to do and which the business community dreaded, or allowing the PP to form a minority government by abstaining at the investiture vote, which is now one of the possible scenarios. UP is the common enemy of the Socialists, the PP and C’s.

Podemos, formed only in 2014 and born out of the movement of the ‘indignant ones’, and C’s (created in Catalonia and which did not go national until 2014) upended the two-party system of the PP and Socialists last December, but since then have not managed to make further inroads into the political establishment. The PP and the Socialists won 222 seats between them, nine more than last December (101 fewer than in 2008).

C’s won 377,000 fewer votes and UP lost 1 million. C’s supporters deserted the party for the PP and UP’s for the Socialists. The UP’s vote (5 million), mostly young adults, was less than the combined vote of Podemos and United Left (6.1 million) last December and represented a big smack in the face for the abrasive campaign and strategy of Pablo Iglesias, the UP leader. It would seem that voters were not convinced by Iglesias’s labelling of UP’s ideology as ‘new social democracy’, to the outrage of the Socialists.

The PP, with the most loyal supporters, many of whom are pensioners, benefited from the lower voter turnout (69.8% as against 73.2% last December) and probably from Brexit and the market turmoil that followed it which probably fuelled a ‘flight to safety’ (represented by the PP) among Spanish voters. Sánchez blamed Iglesias for the rise in the PP’s vote.

The Spanish economy is growing again (the strongest among the big euro zone countries), jobs are being created, albeit mainly temporary ones and the unemployment rate is still above 20% (26% in 2013), and consumer spending is picking up. Rajoy claims credit for the recovery.

Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937), the Italian Marxist theorist, famously declared ‘The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born’. The results of Spain’s election show that the ‘old’ still has a lot of life in it and the ‘new’ has not really yet been fully born. Spaniards are hoping this will not necessitate third elections.