Old age pensioners (OAPs) have been protesting across Spain at their ‘miserable’ pensions which since 2014 have stopped being automatically indexed to inflation and have risen by only 0.25% a year under reforms aimed at making the creaking system sustainable.

The population is ageing at a much faster pace than most other developed countries. Average life expectancy has risen by around 10 years to 83 years since 1975, testimony to the relatively healthier diet and life style of Spaniards and a tribute to the universal healthcare system created over the past 40 years.

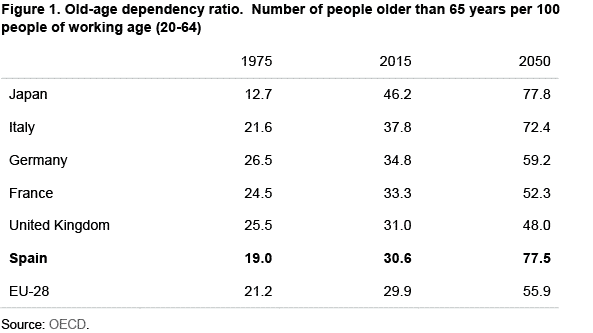

By 2050, Spain will have 15 million pensioners, up from 8.7 million today. Close to 80 people will be above the age of 65 per 100 people aged 20 to 64 compared to 30 today and only 19 in 1975 (see Figure 1). The much higher old-age dependency ratio, which is also the result of the low fertility rate of 1.3 children per woman (2.5 in 1978), will be the second highest among OECD countries after Japan. Deaths have outstripped births in the last two years.

As a result of this ageing, the labour force participation rate (the percentage of the total population aged 16-64 working or seeking employment) and thus a key indicator of the health of the job market will fall from 58% to 50% in 2050, according to the latest IMF projections. The lower the rate the smaller the proportion of the population in a position to work and contribute to the social security system. The IMF says Spain will need 5.5 million more immigrants, roughly the same number that arrived between 2000 and 2007.

The government is already struggling to pay pensions; their number in just the last decade has risen by more than one million as a result of the retirement of the first baby boomers (those born in the late 1950s).

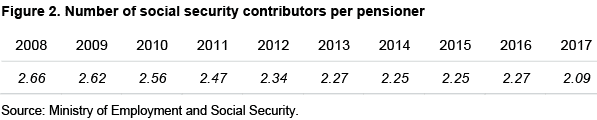

The beginning of their retirement coincided to some extent with Spain’s Great Recession, which saw the unemployment rate soar from 8% in 2008 to 27% in 2013 (down to 16% today). The number of social security contributors is still around one million fewer than in 2007, despite the economic recovery in the last three years. Their number per pensioner has fallen inexorably (see Figure 2).

The reserve fund created in 2000 and built up during the years of the economic boom to help pay future pensions, which peaked at €66.8 billion in 2011, has virtually been depleted. The pension system has been in the red since 2011: last year’s deficit (the difference between revenue and costs) was €18.8 billion (1.5% of GDP).

It should be clear from the above that the demographics and other factors are stacked against Spain and that the government’s room to increase pensions is very limited. Spain’s finances at present are not strong enough to support anything more than a marginal rise in pensions (the budget deficit in 2017 of just over 3% of GDP was within the EU threshold for the first time since 2007), unless there is a substantial rise in tax revenue.

Pensioners have been losing purchasing power, but they have survived Spain’s economic crisis better than young adults, a significant chunk of whom earn well under €1,000 a month and are on precarious temporary contracts which prevent them getting mortgages and onto the property ladder.

The average pension this year is €930 (there is a considerable difference between the highest and the lowest pension). Most pensioners own their homes (unlike, for example, in Germany), which, if circumstances demand it, can be sold.

As well as reducing annual rises in pensions to 0.25% and capping the maximum increase at 0.5% above inflation, if the system can afford it, the statutory retirement age is gradually being increased from 65 to 67 as of 2027 (for both men and women). As of next year, pensions will be calculated with the help of a new ‘sustainability factor’ that links payments to life expectancy –and ensures that pensions will actually fall as the average lifespan increases–.

Other measures need to be taken, such as more companies offering pensions plans and making private pension plans taken out by individuals more attractive (the amount that is tax deductible was reduced from €12,000 to €8,000 in 2015). Saving for a rainy day, however, is beyond the means of a large swathe of the working population who barely get by as it is.

There are also still severe disincentives to combine work and a full pension. Spain is one of only seven OECD countries that applies limits to the earnings above which combined pension benefits are reduced. The pensions of those who continue working are reduced by 50%, apart from self-employed workers earning less than the minimum wage or hiring at least one worker. Furthermore, workers still in employment and receiving a pension do not earn additional pension entitlements although they pay a special ‘solidarity’ contribution of 8%, which does not apply to those continuing to work and deferring the pension.

Populist pension measures to gain votes, which will be tempting for all parties in the next general election campaign, are easy to offer but would come at a cost to the system’s long-term sustainability, which is the key issue.

Politicians running for office are fond of promising ‘jam today’ without doing what it is required for ‘jam tomorrow.’ The pension system is too vital a part of society for irresponsible actions. New measures need to be agreed by consensus.