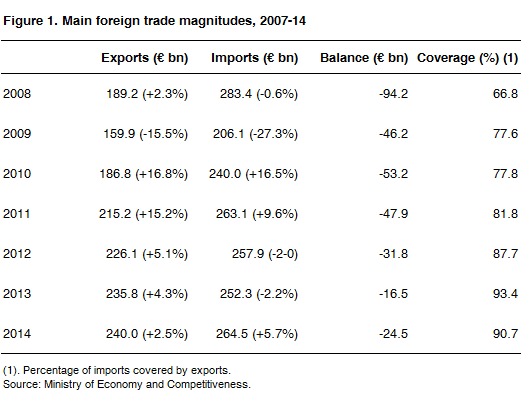

Spain’s merchandise exports rose for the fifth consecutive year in 2014 and set a new record, but their growth was the slowest since 2008. With the economy now firmly recovering, thanks to stronger domestic demand, this slowdown raises the question of whether the export success will tail off (see Figure 1).

Exports rose 2.5% to €240 billion and imports increased 5.7% to €264.5 billion. Import growth was faster than that of exports for the first time since 2006. As a result, the trade balance was 53.4% higher at €24.5 billion, but still low by traditional standards (the second-smallest figure since 1998). The lower trade deficit (€100 billion in 2007 at the peak of the boom when the country was living beyond its means) has helped to turn a staggering current account deficit of 10% of GDP into a modest surplus in the last two years.

The key coverage ratio (the percentage of imports covered by exports) remained high in 2014 at 90.7%, up from 66.8% in 2008, the year the Spanish economy went into a prolonged decline. That year exports were only €189.2 billion.

The €50.8 billion rise in exports since 2008 (more than 5% of GDP) is a remarkable achievement, enabling the country to weather its recession more smoothly. But for the positive contribution of external demand every year since 2008 (reversing eight years of negative external demand), Spain’s recession would have been deeper.

A clear indication of Spain’s greater internationalisation is that changes in global foreign demand are leading to a larger increase in Spanish exports. This can be seen by relating the rise in global demand to growth in Spanish exports before and after the recession. According to calculations by the research department of La Caixa, with the rise in global demand between 2011 and 2013 the annual increase in exports has been 0.8 pp higher than what would have been the case with the pre-crisis export model. The same logic can be applied to the period before the recession.

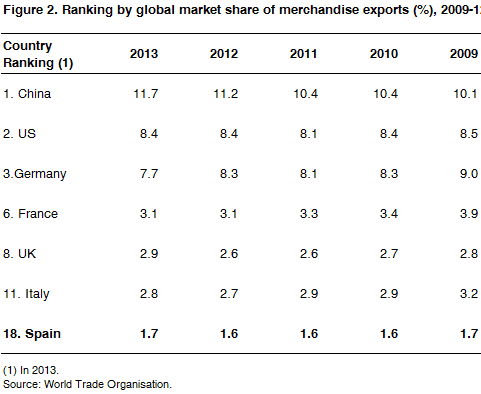

The spurt in exports moved Spain from 20th position in 2012 in the world league table of exporters to 18th place in 2013 (latest year available), as its global market share rose from 1.6% to 1.7% (the same as India). Germany’s much larger share dropped to 7.7%, France stood still at 3.1% and Italy increased to 2.8% (see Figure 2).

Export growth has been faster than Germany’s and France’s, albeit from a smaller base. It has been spurred by productivity gains, restored cost competitiveness and firms, particularly medium-sized ones, making a much greater effort to sell abroad which in some cases has been a matter of survival.

The sharp rise in unemployment has reduced wages in real terms and lowered unit labour costs. The government’s labour market reforms have also enabled companies to negotiate wages and working conditions more flexibly. These factors, in turn, have spurred foreign direct investment in Spain, some of which has gone to major exporting industries, notably the automotive industry.

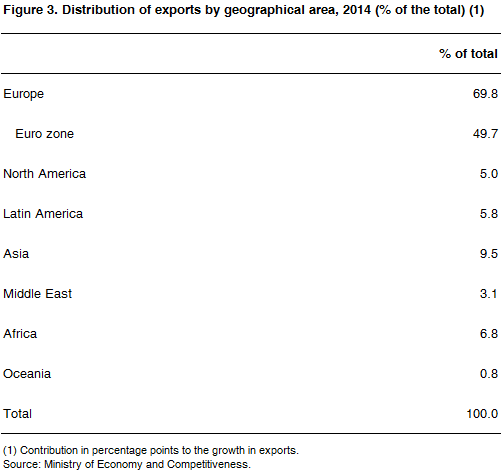

Not only has the volume of exports increased, but there has also been some success in diversifying Spain’s markets outside the EU, which takes almost 70% of total exports (see Figure 3). Sales to the US, a difficult market to penetrate, rose 22.6% and those to Asia 16.3%. Exports to Latin America, however, fell 6.7% and accounted for 5.8% of the total compared with 7.5% for tiny neighbouring Portugal.

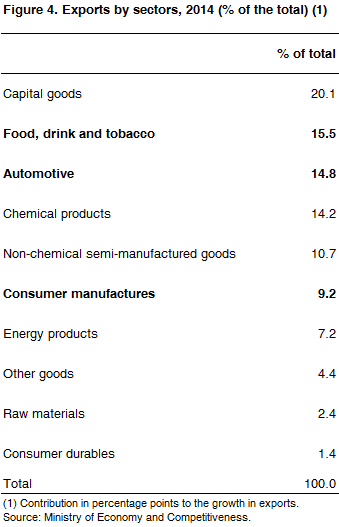

The main sectors that contributed to the 2.5% growth in exports (see Figure 4) were the automotive (0.9 pp), consumer manufactures (0.7 pp) and food, drink and tobacco (0.7 pp).

The question now is whether Spain will be able to consolidate its success and build on it, or whether those companies that only began to export after 2008, as a result of the crisis, will give up because of the stronger domestic market and the ease with which they can sell in it. In other words, is Spain’s export success due to structural or cyclical factors? If it is structural, then Spain will have achieved an important change in its economic model. This year’s exports will give an indication. The European Commission forecasts export growth of 5.4% this year, more than double that in 2014 and above the average EU-28 rise of 4.1%.

Domestic demand is forecast to contribute 2.6 percentage points to this year’s GDP growth, while net exports’ contribution (external demand) will be 0.3 points negative (leaving overall growth at 2.3%), according to the European Commission. In 2013, the last year when Spain was in recession, domestic demand’s contribution was 2.7 points negative and net exports 1.4 points positive, leaving growth at -1.3%.

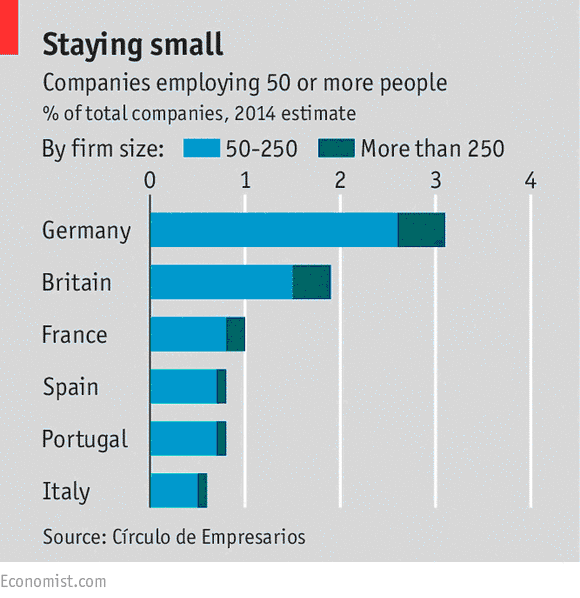

In order to build on its export success, Spain needs more medium-sized and large companies. Almost 40% of employment in Spain is generated by large and medium-sized companies, which respectively account for 0.1% and 0.7% of total companies, while the remaining 60% of jobs are generated by 99.2% of companies –and 95% of firms employ fewer than 10 people–. Only 0.8% of Spain’s more than 3 million companies employ more than 50 workers, compared with 3.1% of German firms (see Figure 5).

Spain’s 100 largest exporters out of a total of more than 150,000 exporters account for around 40% of total exports. Bigger companies tend to be more likely to export and successful at it, as they are likely to be more productive, better able to compete and more resilient in hard times.

The Circulo de Empresarios, a business people’s organisation, and ICEX, the foreign trade institute, among others, are supporting the Cre100do project, which offers information, advice and coaching to 100 medium-sized exporters.

One factor holding back the creation of more medium-sized companies (50-250 workers) is that they suffer the highest effective tax rates, as small ones enjoy concessions and the big ones often manage to find loopholes. Once a company’s annual turnover surpasses €6 million, tax audits become more rigorous. The government needs to change regulations so that medium-sized firms do not feel penalised.

The export success is galvanising the government’s enthusiastic support for the free trade and investment agreement between the EU and the US, known as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), which began to be negotiated in June 2013 and could benefit Spain more than the EU average.