Spain was the world’s third most popular country for tourists in 2013, after France and the US, and it looks like having another bumper year, with international arrivals forecast to set a new record of around 63 million (16.3 million more than the nation’s population).

Tourism is the most flourishing part of the country’s otherwise ailing domestic economy and together with increased exports has played a major role in pulling Spain out of its long recession.

The labour-intensive sector generates more than 11% of GDP and in a country with an official unemployment rate of 26% is a vital creator of jobs. Employment directly or indirectly related to tourism accounts for around 12% of total jobs. Close to 40% of the rise of 178,876 workers who became affiliated to the general social security system in May were employed in the hotel trade, 7% more than in April.

Tourism is nothing new in Spain; the country pioneered mass tourism and package tours. In 1959 the government of General Franco, the country’s dictator from 1939 –after he won the three-year Civil War– to 1975, abolished entry visas for tourists and devalued the peseta, making the country even cheaper for visitors with hard currency. Spain also benefited greatly from the Europe-wide deregulation of package-tour air charters.

Spain was blessed with hundreds of kilometres of virgin coastline that was quickly developed (and much of it eventually ravaged) with hotels and apartment blocks that were cheap by European standards. Benidorm, a sleepy village of fishermen and farmers on the Mediterranean coast in the 1960s, became the archetypal resort for mass tourism and package tours. Today, Benidorm has Europe’s tallest hotel, the Gran Bali, with 52 floors and 776 rooms.

The Franco regime marketed the country during the 1960s under the very successful slogan ‘Spain is different’, which was true in comparison to other European countries –that is, with the notable exceptions of the dictatorships in Portugal (1932-74) and Greece (1967-74)–. The number of foreign visitors jumped 43% in 1960 to 4.3 million, 18 million in 1967 and 30 million by 1975.

Tourism, like the remittances from Spanish emigrants, provided much-needed hard currency and also played an important role in the country’s democratic development because it brought Spaniards into contact with different peoples and ideas, particularly from European democracies, and broadened their horizons. Paradoxically, tourism helped to make Spain a more ‘normal’ country.

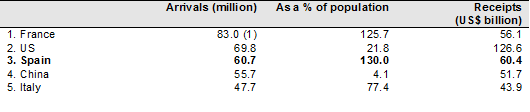

Apart from a drop between 2008 and 2010, the number of tourists has continued to rise; in 2013 it reached 60.7 million, partly thanks to the revolutions in the Arab world, which made tourists switch their holidays from these countries to Spain (see Figure 1). The Canary Islands off the coast of Africa, for example, received 10.6 million tourists last year, five times more than their combined population. Hotels in Barcelona, the capital of Catalonia, enjoyed an occupancy rate of 72% in 2013. Another factor are austerity measures: salaries have mostly fallen in real terms over the past five years (after taking inflation into account) and have restored Spain’s eroded competitiveness.

The receipts from the sector of US$60.4 billion (5.2% of the world total) helped to turn around the current account last year when it recorded its first surplus (0.7% of GDP) since 1990. In per capita terms, Spain’s revenue from tourism was US$1,297 last year compared with US$441 for the US and US$881 for France.

In addition to a plentiful supply of beaches, Spain has 44 UNESCO-declared World Heritage Sites, the most of any country after Italy and despite being a late joiner in 1984 and largely known abroad for little more than its beaches. The list is wide and testimony to Spain’s situation as a cradle of different cultures and civilisations. It takes in almost the entire history and geography of Spain, including Atapuerca near Burgos, where archaeologists discovered human bones in the late 1990s that date back 800,000 years, the Roman aqueduct in Segovia, the Alhambra Islamic palace in Granada and the Route of Santiago de Compostela, along which pilgrims began to walk in the Middle Ages to the city’s cathedral in Galicia where tradition has it that the remains of the apostle St. James are buried.

The collapse of the property and construction sectors that triggered Spain’s recession between 2009 and 2013, apart from a mild respite in 2011, and was largely responsible for tripling the unemployment rate to 26% has left Spain even more heavily reliant on tourism. But tourism, although labour intensive and with a big knock-on-effect, cannot fill the large hole left by these sectors in terms of employment as the sector is markedly seasonal throughout the year, particularly the ‘sun, sea and sand’ variety. The Canary Islands, for example, receive more than 10 million tourists (five times their population) and yet still have an unemployment rate of more than 30%.

One area that can be developed more is cultural tourism, which is not seasonal. Madrid, for example, has the Prado, Thyssen and Reina Sofía art museums, which are near to one another and form what is called a ‘golden triangle’. These three museums receive more than 6.6 million visitors a year, but this is far from the 16 million that visit the British Museum, the Tate and the National Gallery in London. The challenge is to attract more tourists away from the beaches.