The conservative Popular Party (PP) government widely failed to meet the 2015 budget deficit target agreed with the European Commission (EC), leaving a daunting legacy for the next administration, whenever there is one, further eroding Spain’s credibility and straining relations with Brussels which will be asked for more time to get the deficit back below the EU’s ceiling of 3% of GDP.

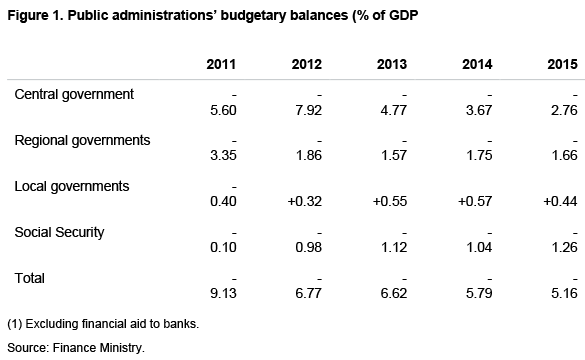

The deficit came in at 5.16% of GDP, almost a full percentage point above the target. Public spending was €55.7 billion higher than government revenues. The deficit is supposed to be down to 2.8% this year, which clearly will not happen.

The overshoot came after warnings last October from the EC and from Spain’s Independent Fiscal Authority for Fiscal Responsability (AIReF, as it is known in Spanish) last July that the target would be breached which were blithely ignored. Brussels forecast a deficit of 4.7%. Luis de Guindos, the Economy Minister, was adamant the government was on track to meet the target of 4.2% and that of below 3% this year. José Manuel García-Margallo, the Foreign Minister, said the ‘only thing the predictions do is legitimize astrology.’

The PP was meant to reach the 3% EU ceiling by 2013, but the dire situation inherited from the Socialist government and the euro zone crisis made this impossible. The deadline was extended by a year, but in 2014 so little progress had been made that the PP won a further two-year extension to 2016. Now this has proved to be beyond its capability.

Moreover, a Budgetary Stability and Financial Stability Law came into force in May 2012 in a bid to strengthen fiscal discipline across all levels of government. This followed the reform of Article 135 of the Constitution in September 2011 in order to guarantee the principle of budget stability. José Luis Escrivá, a former senior official at the European Central Bank, was appointed the head of the AIReF at the instances of Brussels instead of someone of Madrid’s choice who might have been more malleable.

The main culprits for the budget overshoot were 14 of the 17 regional governments, some of which are in leftist hands following last May’s regional elections, and the social security system. The regional deficit was 1.66%, more than double the 0.7% target, and the social security’s 1.26%, twice the 0.6% target.

Income and corporate tax cuts in 2015 were also to blame to a smaller extent. The economy grew by a brisk 3.2% last year, but output was still below the pre-crisis level and the jobless rate was still more than 20%. Growth in government revenues was not as strong as it could have been because of the cuts (income taxes were raised in 2012). Furthermore this move did nothing to bolster the PP’s electoral chances: it lost its absolute majority in the inconclusive election on 20 December. Spain has not had a proper government since then.

The government of Catalonia, which is pushing for independence, had the largest budget deficit (2.7%). That of Valencia, ground zero of Spain’s real-estate bubble, epicentre of a string of corruption cases and the former fiefdom of the Popular Party (it enjoyed an absolute majority for 16 years) until a leftist government won power last May, was 2.52%.

While the central government deficit has come down from a whopping 7.92% of GDP in 2012, the PP’s first year in office and excluding financial aid to ailing banks, to 2.76% last year, the social security deficit has risen almost every year since 2011 (see Figure 1).

The social system is headed toward a crisis. In order to pay state pensions the government raided the reserve fund built up during the boom years, reducing it from a peak of €66.8 billion in 2011 to €32.4 billion at the end of 2015.

Despite negative inflation of 0.5% in 2015, this year’s pensions were increased by 0.25%, the minimum annual rise laid down in the government’s pension reform which took effect in 2014. No one at that time thought Spain would have deflation.

Pensions and unemployment benefits are the two largest social security costs. In 2015, 29% of the population (13.56 million) received economic benefits from the state. The number of social security contributors (17.3 million in March) is still well below the peak of 19.5 million in 2007.

The incumbent PP government is limited in what it can to do. Meanwhile, there are no solid signs of progress in forming a new government, following the failure of the Socialist leader Pedro Sánchez to win support earlier last month from the PP and the anti-austerity Podemos for his coalition government with the centrist Ciudadanos (C’s).

If no political leader obtains the required support by 2 May King Felipe will dissolve parliament and call a new ballot, probably to be held on 26 June, which could produce another stalemate. The latest Metroscopia poll published in El País on 3 April gives the PP 27.7% of the vote (28.7% last December), the Socialists 21% (22%), C’s 18.8% (13.9%) and Podemos and its regional allies 15.0% (20.7%).

No party would again be anywhere near an absolute majority. The PP would still be the most voted party. Mariano Rajoy, the incumbent Prime Minister, turned down the king’s offer in January for him to have the first shot at forming a government because of a lack of support from any party.

The agreement between the Socialists and C’s (24 February) includes asking Brussels for another year to meet the 3% target. The larger than expected overshoot is perversely good news for them as it enhances their call, but bad for the euro zone. The next government faces some brutal choices, and the sooner it makes them the better.