The recent snap election in Andalucía saw the far-right party Vox storm into the regional parliament with 12 of the 109 seats, and so end Spain’s exceptionalism.

Until then Spain, to the surprise of many, had bucked the nationalist surge that has swept across the EU, with, for example, France’s anti-immigrant and anti-system National Rally and Germany’s AfD, despite having, in the view of analysts, the conditions for such a party including very high unemployment and a large foreign community. The anomaly is viewed as a legacy of the 39-year right-wing dictatorship of General Franco, who died in 1975.

France’s far-right leader Marine Le Pen was quick to tweet (in French): ‘Strong and warm congratulations to my friends from Vox, who scored a meaningful result for such a young and dynamic movement’. Steve Bannon, Donald Trump’s former chief strategist at the White House, offered technology services before the Andalusian campaign to help Vox put across its message in social media, but they were apparently not taken up.

“Yet there are clear grounds for believing that Vox is here to stay”.

Whether Vox’s victory –395,978 votes (11.9% of the total) as against just 18,422 (0.46%) in the 2015 Andalusian election– will see it going from strength to strength in next May’s municipal, regional and European elections and a general election if one is called ahead of the due date of July 2020 remains to be seen. Yet there are clear grounds for believing that Vox is here to stay. It won a mere 47,182 votes (0.2% of the total) in the 2016 general election.

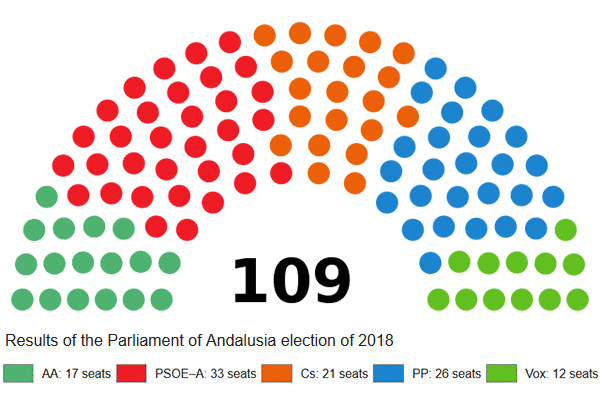

Vox’s first success was largely at the expense of the conservative Popular Party (PP), which lost 316,409 votes and seven of its 33 seats, and to a much lesser extent the Socialists (402,035 and 14 of its 47 seats, respectively). The latter’s voters mainly switched to the liberal Ciudadanos (C’s, which won 21 seats, 12 more) and to some extent the leftist coalition Adelante Andalucía (AA) whose main component is the far-left populist Podemos and which until Vox was the main recipient of anti-establishment votes. The voter turnout of 58.6% was the lowest since 1990.

The Socialists won the most seats (33) of all the parties but it was their worst performance ever in their stronghold, which they have ruled for 36 years. AA’s 17 seats are not enough for the Socialists to carry on governing the region, and the PP (26 seats) will need the 17 seats of C’s and Vox’s 12 to form a very narrow majority government or a minority one with parliamentary support from Vox.

That the political earthquake caused by Vox, created five years ago by Santiago Abascal, a former PP politician, should happen in the leftist stronghold of Andalucía, which provides 20 of the Socialists’ 84 seats in the national parliament, surprised many (polls forecast a maximum of four seats). Yet there are fundamental factors why it happened in Spain’s largest region (population 8.4 million). As well as the fatigue with having been ruled by the same party for so long and the corruption scandals that have engulfed the Socialists, Andalucía has an unemployment rate of 23% (8 pp above the national average) and a very large immigrant community, particularly from non-EU countries.

This is particularly the case in the province of Almeria where 18.5% of the 700,000 population is foreign, mainly Moroccans and Sub-Saharans, well above the 10% for Spain as a whole. Eight of the 10 municipalities with the largest growth in votes for Vox were in Almeria, and in all of them more than 20% of votes went to Vox (30% in the case of one of them).

Non-EU foreigners tend to be employed in the sectors that Spaniards do not want to work in, particularly agriculture (sweating under a ‘sea’ of plastic greenhouses in areas like El Ejido) and are perceived as a drain on healthcare and education, although they are in fact net contributors to social security. They are also viewed as a threat to Spanish identity, even though many of them have been there for years.

The surge in illegal immigration this year will also have fed into people’s fears of the ‘other’. In the first nine months, there were 7,120 illegal crossings of Moroccans to Spain via the Western Mediterranean (see Figure 1).

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 254 | 300 | 776 | 365 | 282 | 468 | 631 | 722 | 4,704 | 7,120 |

Spanish society has changed profoundly since Franco died and the country successfully moved to democracy. The country is no longer ethnically homogeneous: the number of registered foreigners has risen from 165,000 to 4.7 million, excluding the more than 700,000 naturalised Spaniards. Not all the change has been to the liking of conservatives, particularly personal-freedom issues such as the legislation of abortion and gay marriages (the latter in 2005). In addition, there is no longer a stigma about voting for the far right as there was in the first post-Franco years.

The election in Andalucía was the first since the one in Catalonia at the end of 2017, which saw those parties in favour of unilaterally creating an independent republic holding onto their narrow majority in the Catalan parliament. That election was followed in June of this year by the unseating of the PP national government, following a censure motion in parliament won by an unholy alliance of the Socialists, Basque nationalists and Catalan secessionists.

The right has not forgiven the Socialists, with only 84 of the national parliament’s 350 seats, for attaining power by this means thanks, in part, to Catalan parties who want to break up Spain. Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez is regularly attacked by the right for not being firm enough with the secessionists.

“The question now is whether Vox’s success is a flash in the pan or the start of something more significant”.

The Andalusian election was an opportunity to punish the Socialists and not just for local reasons, and also the PP, which has never won enough votes in the region to make a difference. Vox’s votes have achieved change, although its shape has yet to be determined.

The question now is whether Vox’s success is a flash in the pan or the start of something more significant. The evidence shows that once a party is installed in a parliament, be it regional or national, support for it tends to grow. This has been the case of Ciudadanos, which began life in Catalonia in 2005 against the burgeoning independence movement and after gaining three seats in the Catalan parliament in the region’s 2006 election moved out of its territory and won nine seats in the 2015 Andalusian election (21 in the latest election). This was then followed by winning 40 seats in the national parliament in the 2015 general election.

Moreover, in the case of ‘stigmatised’ parties, such as those on the far right, winning parliamentary representation makes them more respectable and hence an option for voters. Fourteen European countries have far-right parties in their parliaments (see Figure 2).

| Country | Name of party and % of votes |

|---|---|

| Austria | Freedom Party (26%) |

| Bulgaria | United Patriots (9%) |

| Cyprus | ELAM (3.7%) |

| Czech Republic | Freedom and Direct Democracy (11%) |

| Denmark | Danish People’s Party (21%) |

| Finland | The Finns (18% |

| France | National Rally (13%) |

| Germany | Alternative for Germany (12.6%) |

| Greece | Golden Dawn (7%) |

| Hungary | Jobbik (19%) |

| Italy | The League (17.4%) |

| Netherlands | Freedom Party (13%) |

| Slovakia | Our Slovakia (8%) |

| Switzerland | Swiss People’s Party (29%) |

Prepared by the BBC.

Since 2015, when the mould of Spain’s essentially two-party system was broken by Podemos and Ciudadanos, political life has become fragmented and parliament gridlocked. Vox could well intensify that fragmentation by adding a fifth party.