The two upstart parties, the centrist Ciudadanos (‘Citizens’) and the anti-austerity Podemos (‘We Can’), broke the hegemony of the conservative Popular Party (PP) and the centre-left Socialists (PSOE), the two mainstream parties that have alternated in power since 1982, but produced a very fragmented parliament that makes the creation of a stable government fraught with difficulties.

“What is crystal clear is that the shape of Spanish politics has changed significantly and will have to be much more consensual.”

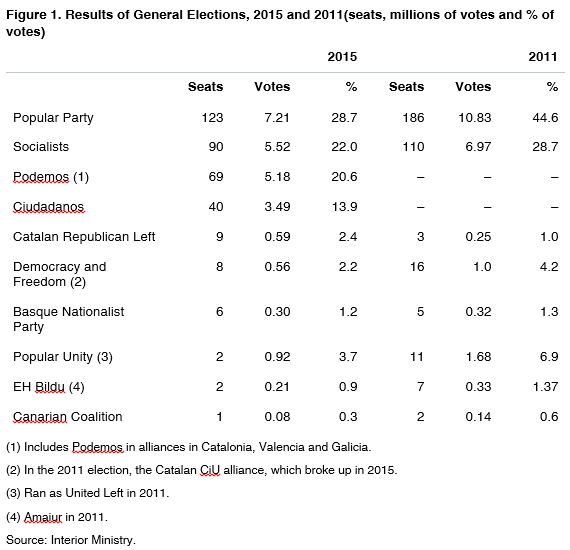

The PP won the most seats (123 out of 350), but way down on its absolute majority of 186 (see Figure 1). Mariano Rajoy, the incumbent PP Prime Minister, failed to convince Spaniards that he was the best bet for continuing the economic recovery. Had Ciudadanos obtained as many seats as the opinion polls had predicted, it would probably have been the kingmaker and probably backed a minority PP government. But its 40 seats still leave the PP 13 seats short of the ‘magic number’ of 176. The combination of the Socialists and Podemos (159) is also short of a majority (17), but could make it if some deputies from Popular Unity and Basque and Catalan nationalists come on board.

The one option that would work and the most logical would be a German-style grand coalition between the PP and the Socialists, which would give such a government a comfortable majority (213 seats). But neither of the mainstream parties wants this, particularly the Socialists whose dominance of the left has been shattered by the surge from nowhere of Podemos, a party that was only formed in January 2014.

Everything is thus up in the air, and a fresh general election next year cannot be ruled out. What is crystal clear is that the shape of Spanish politics has changed significantlyand will have to be much more consensual.

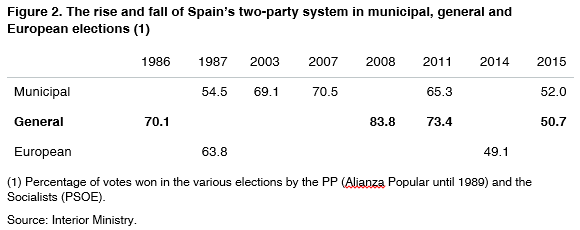

The PP’s and the Socialists’ share of the vote plummeted from 73.3% in 2011 to just over 50% (see Figure 2), while Podemos and Ciudadanos between them won 34.5%. The two mainstream parties are severely but not mortally wounded: the number of PP seats in parliament is the lowest since 1989 (107) and the Socialists the lowest since 1977 (118). The two traditional parties, however, maintained their hold on the Senate, winning 171 of the 208 elected seats (58 are appointed by regional parliaments).

Ciudadanos and Podemos channelled the anger at a long succession of corruption scandals and the economic and social impact of a long recession. Spain experienced one of the steepest declines in confidence in national governments between 2007 and 2014, according to the OECD’s Government at a Glance 2015 report. Confidence fell 27 percentage points to 21% compared with a decline in the OECD average from 45.2% to 41.8%.

Disaffection with the political establishment was also accompanied by a demand for generational renewal: Albert Rivera, the Ciudadanos leader, is aged 36, Iglesias is 37, while Pedro Sánchez, the Socialists’ leader, is 43 (he replaced the 64-year-old Alfredo Pérez Rubalcaba in 2014) and the Popular Party’s Mariano Rajoy is 60.

The main surprise was the performance of Ciudadanos, which opinion polls before the election predicted would win more than 60 seats, ahead of Podemos. The outcome on the day, however, was bound to be uncertain because up to 40% of the electorate had not made up its mind –a far higher proportion than in any other general election–.

The clear victor was Podemos; its results were something of a personal triumph for the pony-tailed Pablo Iglesias. The party began as a kind of offshoot of the United Socialist Party of Venezuela, founded by the late Hugo Chávez, the country’s President for 11 years. In a U-turn following Podemos’s realisation that many of its sympathisers viewed the party as far more radical than themselves, the charismatic Iglesias distanced himself from a country plagued by food shortages, the world’s highest inflation rate and the regime’s US-bashing ideology propagated by Chávez and his successor, Nicolás Maduro. Podemos presented itself as a Nordic-style social-democrat party.

Podemos was particularly successful in Cataloniawhere in an alliance it won 12 seats, the largest number and more than Democracy and Freedom, the new nationalist party of Artur Mas, the incumbent regional Prime Minister of Catalonia, who since September’s election in the region has failed to win enough parliamentary support to carry on. In that snap election, billed as a de facto vote on establishing a separate state, the Junts pel Sí alliance (‘Together for Yes’) won 62 of the 135 seats in the Catalan parliament. Mas has one more chance to win sufficient backing in the regional parliament. The options in Catalonia are someone other than Mas as prime minister or fresh elections.

Podemos rejected the notion that September’s election could be considered a referendum on independence and focused for the general election on issues such as unemployment and corruption. It is, however, the only party of the four main ones that supports the right of Catalans to have a legal and binding referendum on whether to establish a sovereign state.

Spain has entered uncharted waters. The general election showed widespread support for change. What shape it will take remains to be seen.