At some point before the summer Spain will regain its pre-crisis (2008) GDP level. This will doubtless be the cause of some celebration in the conservative Popular Party (PP) government, which for the last six years has been getting to grips with the problems.

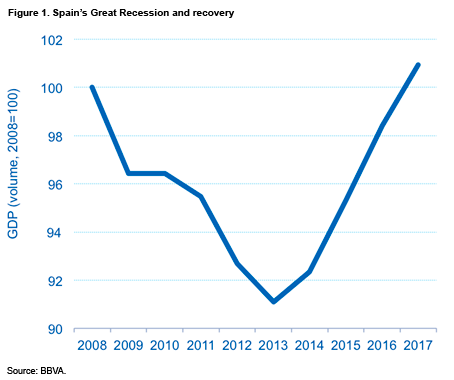

Spain’s Great Recession, following the debt-fuelled, real-estate backed boom, saw GDP shrink 9% between 2008 and the middle of 2013 when the economy began to recover (see Figure 1), thanks, initially, to record exports and tourists, among other reasons, and more recently a recovery in domestic demand.

Even the property sector is picking up: housing starts in 2016 are estimated at 62,000, down from 865,000 in 2006 (more than Germany, France and the UK combined).

The jobless rate has fallen from a peak of 27.3% in 2013 to 18.6% last year and is continuing to fall, while the current account has been turned around –from a whopping deficit of 9.6% of GDP in 2007 to a 2% surplus last year.

On the fiscal front, the government met in 2016, for the first time since 2008, the budget deficit target set by the European Commission after endless overshoots and re-negotiating with Brussels.

The deficit came in at 4.54% of GDP, just below the 4.6% target, and way down on the 11% deficit in 2009. Spain has until 2018 to finally reach the EU’s reference value of 3% of GDP (a target that was supposed to have been attained in 2013).

Parliament, however, has yet to approve the 2017 budget, as a result of two inconclusive elections and 10 months without a functioning government (a minority one since October 2016).

The central and regional governments have reduced their deficits and local governments are in surplus, but the social security accounts continue to deteriorate (deficit of 1.62% of GDP in 2016, up from 1.22% in 2015, compared to a surplus of 1.4% in 2008). Further pension reform is needed.

In order to meet pension payments, the government has raided the reserve fund created in 2000 by the Socialist government. The reserve stood at around €15 billion at the end of 2016, down from a peak of €66.8 billion in 2011. There is enough for July’s extra pension payment, but after then the government will issue public debt to meet payments.

The social security’s accounts have been hard hit by a combination of a sharp fall in the number of contributors (from 19.5 million in 2007 to 7.9 million in March 2017), as a result of massive unemployment, and the inexorable ageing of the population.

Gross public debt has surged from 36.2% of GDP to around 100% (the EU’s reference value is 60%) and is regarded by some as the elephant in the room. The Treasury’s funding needs this year are put at €220 billion between debt maturities and net issuances. In 2016, the average maturity of public debt was 6.8 years, similar to that recorded at the start of the crisis. The lower financing cost, however, thanks largely to the European Central Bank’s accommodative policy, has led to significant savings in interest payments. Spain is one of the main beneficiaries of the ECB’s policy.

In order to gradually reduce the public debt, Spain needs to continue to cut its fiscal deficit so as to ensure that once interest rates start to rise again the elephant does not lash out.

The banking sector, which threatened to collapse like a house of cards when Bankia, the fourth largest bank by assets, and several savings banks had to be bailed out by the EU, is now in much better shape, except for Banco Popular, the sixth biggest, which is on the rocks as a result of its toxic loan portfolio.

Spain’s economic achievements have made it something of a poster boy for some EU countries, although that image was somewhat tarnished by squabbling politicians failing to form a new government for most of 2016.

Challenges remain; the most important in human as opposed to macroeconomic terms is the still very high unemployment rate (double the EU average). The PP’s labour market reforms in 2012 have clearly helped to lower the jobless rate by reducing severance payments and giving companies greater discretionary powers to adopt internal measures to limit job destruction, among other factors, but there is still a yawning gap between ‘insiders’ (those on permanent contracts) and ‘outsiders’ (those on precarious temporary contracts).

The IMF recently urged the government to undertake further labour reforms in order to reduce the duality. A particularly pressing problem is long-term unemployment: more than 55% of the total unemployed of 4.2 million have been without work for more than a year.

Spain’s growth this year (2.6%) will be the highest among the main developed countries, according to the IMF, but this is of little comfort for the army of unemployed. The government estimates growth will be nearer to 3%.

Spain has won the war, but not yet the battle.