Both Spain and Greece have far-left anti-establishment parties, born out of indignation at many years of austerity and endemic corruption, that look like toppling established parties in both countries, in Greece’s case on 25 January when a snap general election is held.

Greece’s Syriza and Spain’s Podemos, part of the same bloc in the European Parliament, want an end to austerity and a major restructuring of their countries’ debt. Syriza is pressing for debt forgiveness, whose consequences could include Greece’s exit from the euro zone. This is considered unlikely, although Germany appears to be more sanguine about a Grexit. Finland has already emerged as a major hurdle to a negotiating a new bailout deal with an incoming Greek government.

Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy’s visit to Greece on 14 January to show political support for Antonis Samaras, his embattled counterpart, has cast a spotlight on the similarities between the two countries. They certainly exist, but so do differences –and to a greater extent–.

First, the Greek crisis has been much deeper than Spain’s: its GDP has fallen by around 25% compared with 7% for Spain. Greece, unlike Spain, was forced to accept a sovereign bailout by the ‘troika’ (the European Commission, the European Central Bank and the IMF). Some of Spain’s banks, however, had to be rescued. Madrid exited this programme a year ago, whereas Greece is still beholden to the ‘troika’.

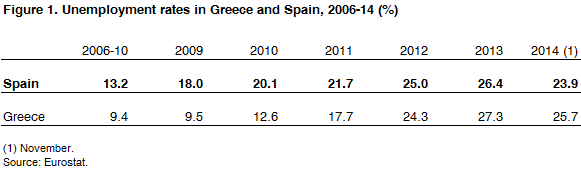

The unemployment rates in both countries are similarly massive (see Figure 1). Spain destroyed 3.8 million jobs between 2007 and the third quarter of 2014, according to Eurostat, and Greece’s much smaller economy (2% of euro-zone GDP compared with Spain’s more than 10%) 1.1 million. While Spain generated 553,400 jobs during this period (representing 14.5% of those shed), Greece created 107,000 (9.2%).

As well as a weaker labour market, Greece’s general-government gross debt is much higher than Spain’s (175% of GDP as against almost 100% and considered unsustainable and not just by the radical left), which explains Syriza’s determined push for debt forgiveness that is frightening Europe’s leaders. Greece began its crisis with a debt load of more than 100%, while Spain’s level was under 40%. Both countries are running current-account surpluses in GDP terms (an estimated 1.5% for Greece last year and 0.2% for Spain).

More than any other European leader, Rajoy stands to lose the most if Syriza wins the election as his government’s austerity measures, more than Greece’s, are producing a glimmer of light in what has been a long tunnel of recession. Rajoy’s dogged sticking to orthodox reforms and spending cuts has made him something of a poster boy for the fiscally-conservative German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

‘The recovery in Spain is undeniable’, trumpeted Luis de Guindos, the Spanish Economy Minister. ‘We have now had growth for six quarters, job growth is faster than expected and tax revenues are on the rise. Spain is outperforming its peers in Europe and, according to the European Commission, we will continue to outperform this year and next. Spain never lost the ability to fund itself, and never lost access to the capital markets. If you look at the spreads now, they are at an all-time low’.

Bond yields show there has been a decoupling between Greece and the rest of southern Europe, including Spain. The risk premium (spread) on Spain’s 10-year government bonds over the benchmark German bunds has come down from 3.54 percentage points in October 2011, one month before the general election which swept the Popular Party back into power, to just over one point, while Greece’s has declined from 23 pp to 9.

Among the crisis-hit countries Spain has been the most reform minded. The labour market is less dysfunctional, as a result of reforms in 2012 that have reduced severance payments for unfair dismissals and given companies greater flexibility to set wages and working conditions themselves rather than through sector-wide bargaining.

Spain is now creating jobs at lower rates of GDP growth than before. In previous cycles, employment rose when growth hit 2%. Jobs were created last year with growth of around 1.4%, though many of them are temporary and precarious. GDP growth this year is put at more than 2%.

Both Spain and Greece, however, still rank at the bottom of the World Bank’s latest classification of countries by the number of weeks of indemnity pay for termination of a contract after 10 years’ employment in the same company –26 in the case of Greece and almost 29 for Spain–.

A Syriza victory could boost Podemos’ electoral prospects, though this could easily change if Syriza’s policies fail to make any headway or deepen Greece’s crisis, and produce an unravelling of the conservative Popular Party’s reforms if the party does well in Spain’s election due to be held by December.

The latest voter-intention poll by Metroscopia, published on 11 January, gives Podemos 28.2% of the vote, the Socialists 23.5% and the Popular Party 19.2%. Whereas Syriza looks like forming the next Greek government, none of the main Spanish parties would be in this position if, as the polls suggest, they all obtain between 20% and 30% of the vote. In this situation, the colour of the next Spanish government is far from certain and Podemos would not be able to govern on its own. It would need to form a coalition with the Socialists. By splitting the left-wing vote, it is not beyond the realms of possibility that the Popular Party continues in power, although without an absolute majority.

The real test of the extent to which Spain is not bracketed in the same basket case category as Greece will come if, as expected, Syriza wins and its victory contaminates Spain. No one is sticking their neck out and saying the contagion for Spain would be minimal, but the improvement in the country’s macroeconomic fundamentals would suggest that Rajoy need not be too nervous.