The upcoming elections in Spain gives the opportunity to talk about the future vision of the Spanish economy. In this vision, digitalisation should place a central role. This post outlines why digitalisation is important, why investing in digital infrastructure is not enough, and why the EU single market is fundamental if this vision is to succeed.

The Spanish digital economy is taking off. Some companies are global successes, while many others show positive signs of growth. This is exciting. It proves that the Spanish economy, its start-ups and entrepreneurs have the ingenuity and capacity to create and deliver digital services which are demanded across the world.

The health of the Spanish digital economy is important for everyone. Digital services and technologies such as computers or software, usually referred under the label of Information and Communication Technologies or ICTs, enhance productivity by helping companies to do their jobs more efficiently. These gains in productivity are one of the prime sources of our shared prosperity.

Yet, for digitalisation to lift the average productivity of the economy, digital technologies need to be embraced not just by the technological companies but throughout the economy. What makes digitalisation economically valuable is that innovative technologies power other sectors in the economy and contribute to better performance. It is the adoption of digital technologies that leads to better productivity and smarter use of resources, and that adoption should take place across the entire economy. This is the challenge for any future government.

Spain invested heavily in its digital infrastructure, providing almost universal access to the Internet to households and businesses. This access has become faster with the expansion of broadband, which is now more affordable.

Some figures illustrate this vividly: more than eight in ten Spanish households have broadband Internet in their homes (83% in 2017 compared to 28% in 2006), while 78% use mobile devices to access the Internet on the move. Similarly, nearly all Spanish firms have access to Internet broadband, and the cost of a faster Internet connection has gone down year-on-year. Moreover, Spain has the largest network of fibre optic only behind South Korea and Japan. This is a remarkable achievement which shows Spain’s ability to build a world-class infrastructure capable of delivering a fast Internet connection almost universally.

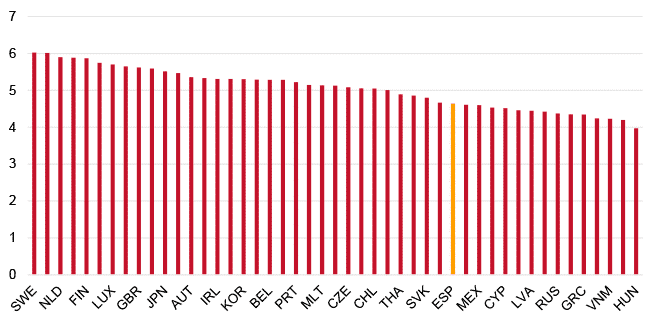

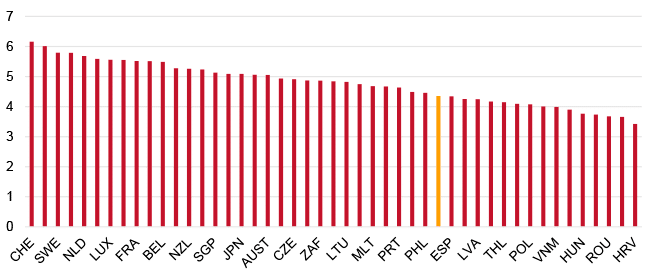

Still, investing in infrastructure is not enough. What matters is what we do with that investment. Individuals, firms, and the public sector need to use these technologies so the benefits of the digital economy can be materialised. And Spain lags behind other economies in its ability to transform the investments in digital infrastructure into economic output. As an example, these figures show that Spain falls behind comparable European economies and emerging economies in Asia.

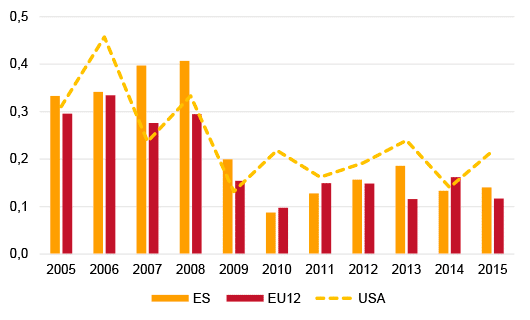

More investment alone will not necessarily bring higher levels of digital output. Spanish policy makers should be well aware that technology has blurred the boundaries between digital and the non-digital economy. There are policies and regulation in the digital and the product market hindering the diffusion and development of the Spanish digital economy. This is reflected in the data. Spain belongs to a group of European countries with higher than average restrictions on digital trade (the 4th highest after France, Germany, and Romania) and these restrictions have negative impacts on Spanish productivity (lifting data policies restrictions would increase Spanish productivity by almost 5%).

Moreover, technology does not work in a vacuum. The adoption of new technology is costly, and more often than not, companies need encouragement to switch to new technologies. This encouragement usually comes in the form of competition and the prospect of increasing sales.

Here, the European Single Market stands at the centre. Europe could significantly improve the economic payoff from digitalisation by removing policies and regulations that either are very restrictive or that differ significantly across Europe, leading to markets that are fragmented along national borders. While ICTs and digital platforms have empowered business to reach other markets at a low cost, regulatory barriers and regulatory heterogeneity deny European companies the benefits of the economies of scale and network externalities coming from rolling out digital business models across the EU.

Moreover, opposing digitalisation because of the possible effects on the labour market would be like opposing steam power, electrification or motor vehicles[1]. While technological progress has costs, particularly for those whose jobs are threatened by new technologies, the benefits of this progress have historically outweighed the negative effects. The Spanish (and European) welfare system and active labour market policies are the safety net to embrace technological progress and digitalisation without fear of social upheaval. Besides, digitalisation could be used as a tool to fight economic rents in protected industries and services and therefore reduce inequality.

In the European context, Spain should not be shy about the strength of its digital economy and should proactively work with like-minded countries such as the Digital 9 (Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK) to deepen Europe’s Digital Single Market. It should propose policies that reach beyond the traditional data policies, putting down regulatory barriers in the European Single Market which curb the benefits of the digital economy, digital diffusion and lower the payoffs from investing in digital infrastructure.

[1] History has many anecdotes of such opposition which in the present time sound as counterproductive ways to stop the inevitable technological progress. For instance, in the Globotics Upheaval, Richard Baldwin tells the story of the the UK Locomotive Act of 1865 which required that one person, wearing a red flag, should precede every locomotive propelled by steam and as a result no locomotive went faster than walking speed. This law stifled the automobile industry in Britain for three decades and it was repealed in 1896.