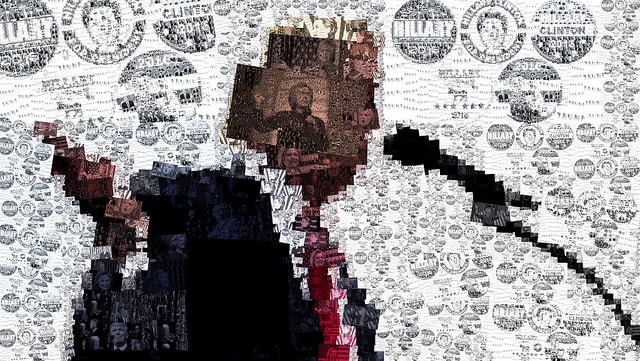

The US presidential elections have shown that democracy has changed, and the means of obtaining victory, too. Hillary Clinton’s team (despite winning the popular vote) erred. It spent more than US$200 million on TV advertising, twice what Donald Trump spent. Clinton also spent US$30 million on the social media –and before her the social-democrat Bernie Sanders used it to bolster his campaign too– but Trump invested more heavily still (at almost US$90 million) in ads that drove his messages home and reached more people. The social media enable campaigns to make closer contact with the voters they want to reach, to raise funds and transmit ideas, often simplistic. They played an even more crucial and decisive role in this campaign than previous ones, and many outside the US will mimic it in others. In fact, it had already been tried successfully by proponents of leaving the EU in the Brexit referendum. Naturally there are other reasons for winning, but by their very nature the social media amplify them, due to the uses they can be put to.

Accusations abound that such networks have been manipulated to seed “emotional contagion”, and spread disinformation and fake news, like the claim that Pope Francis was a Trump supporter. This has unleashed a wave of criticism towards Facebook (the primary source of news for 44%, in other words almost half, of Americans according to a Pew Center survey), Google and Twitter. But it had already happened with lies in the Brexit campaign, which were also amplified by the social media, and with the populist Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines. The US is usually at the forefront in these issues. But, once again, electoral campaigns in democracies, and even world politics, will change when there are billions of users on networks that have been in existence for less than a decade.

Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and CEO of Facebook, with 1.8 billion users worldwide, has had to come out in his own defence, flatly rejecting the claim that his social network could have influenced the presidential elections. All such companies are reviewing their policies on such matters, however. And in this respect it seems easier to modify the algorithms they rely on in order to curtail fake news than it is to change the ideological and emotional bias inherent to some of them. In 2013 Facebook conducted an experiment in the US to demonstrate such bias, putting news on almost half a million users’ walls that reinforced their preferences, the results of which it published. Politics has a significant emotional component, as Manuel Arias Maldonado skilfully argues in his book The Sentimental Democracy (2016). These feelings can be transmitted to others through the social media by means of emotional contagion, leading people to experience identical feelings without being aware of the process. In other words, they lend themselves to generating emotional identification. And, quite clearly, to manipulation. It is nothing new. Various studies have been warning for some time about “political polarisation” in Facebook and other media, which Obama used so well in his campaigns.

Zuckerberg, in his defence of Facebook as a non-partisan platform, said that his company “must be extremely cautious about becoming arbiters of truth”. But this does not mean that others cannot manipulate it, or use its operating methods, its own algorithms, to their own ends. For its part, Google has said that it will ban websites that publish fake news from using its advertising service, whereby recommended news stories and links appear more prominently higher up the page.

In fact, one of the websites that pushed hardest in this direction in the recent campaign was the extremist Breitbart News Network, which has been climbing up the rankings of importance and visits and has considerable impact on the social media. Its chairman, Stephen K. Bannon, took leave of absence to campaign for Trump, who has now made him a chief strategist and senior counsellor in the White House.

Are we witnessing the advent of what Kelsey Campbell-Donovan calls “algorithmic democracy”? In fact, a study by Alessandro Bessi and Emilio Ferrara, at the University of Southern California, has found that 20% of political tweets sent out during the campaign, whether pro-Trump or pro-Clinton, originated from bots, not humans, of unknown provenance, which could indicate foreign interference in domestic elections. It is a matter of concern that such bots could alter public opinion “and endanger the integrity of the presidential elections”, in the words of the researchers. Some trace the origins of the bot-created messages to the US state of Georgia and to Macedonia. But the geographical location matters little in this world. They are not strictly speaking artificial intelligence (AI), but they are behaving in way that is more and more autonomous in this area.

The AI used by Facebook, and other firms, learns and feeds the users of the network with what it finds out about their own preferences. In other words, it reinforces users’ political ideas and prejudices, wherever they may come from, something that encapsulates in a new context Nicholas Negroponte’s original idea of the Daily Me, the imaginary newspaper that gives readers only what they want to read; except now we are in the era of social media, so that we end up being informed, if it can be called that, only about what we believe. There are no surprises or cognitive dissonances to feed a dialectic of contradictions. On the contrary, blind-spots get reinforced. The Islamic State (IS) also uses them in its recruitment campaigns and ideological propaganda. As I warned in La fuerza de los pocos (2007) –which predated the emergence of social media– the Internet and the new media empower individuals and groups that before were on the margins. This was seen in the first uprisings of the Arab Spring and the 15-M movement in Spain. But now we are seeing an explosion in terms of the scope and operating methods of these social media and their impact on the way democracies work.

The artificial intelligence that underlies the social media could also have served to predict the result of the US election. A neural network created by Edward Cantow used, prior to 8 November, 14 million images, linking them to 21,000 categories. The results revealed that the top five associations with Trump were ‘president’, ‘secretary-general’, ‘US president’, ‘executive director’ and ‘the minister’, whereas the top five for Clinton were ‘Secretary of State’, ‘donna’, ‘first lady’, ‘auditor’ and ‘the girl’. It represents the triumph of what Jarno Koponen calls ‘personalisation’, which ‘creates a striking gap between our real interests and their digital reflection’. It is the digitalisation of Plato’s allegory of the cave.