With the fight against the coronavirus pandemic obliging them to work remotely, many Silicon Valley companies, both large and small, have told their employees not only to do so from home but have announced that this situation could persist indefinitely. It may lead to a cultural shift in which this central ecosystem of the contemporary landscape could be transformed or lose part of its essence or modus operandi, although in fact the trend was already under way. Once again, the pandemic has acted as a catalyst, with lessons for all concerned.

Microsoft foresees homeworking until at least October, while Google has extended this until the early part of 2021. Twitter has told its employees that they may carry on working at home, if they prefer. Twitter, Square, Coinbase, Box and Shopify, among others, have been joined by Facebook, announcing a shift towards more remote working, something they view as positive, although new tools and techniques would be needed to manage it. Meanwhile partners in a growing number of start-ups are beginning to ask that offices are not even established and that entrepreneurs should shun Silicon Valley to save costs. This is a marked change of mindset when just a few years ago it was impossible to raise funding without being physically based in the area, without traipsing through the offices on the famous Sand Hill Road, the Wall Street of Silicon Valley.

That this is possible is due largely to some of these companies inventing the tools that have made remote working viable and will make it even easier still: not only the high-bandwidth Internet but also cloud computing, essential for carrying out what is being achieved. Amazon –and subsequently others– changed reality by renting out their servers, enabling any individual or company in the world, with far fewer resources, to launch a high-quality, stable web service, such as the videoconferencing systems that have become indispensable during lockdown. Many companies have paid their employees a bonus (often US$1,000) to buy themselves a desk and an ergonomic chair from which to work, plus supplements to improve their mobile and Internet connections from home, perks to ensure employees do not have to shoulder office running costs.

However, will a remote-working version of the Valley –totally remote, not partially as many of the world’s companies, including Spanish ones, have already tried– be able to maintain its creativity and consequent innovation? Over the course of history, science has often made progress at a distance, with the publications and letters that scientists have exchanged. And increasingly more and better companies are specialising in networked design. As Lynda Gratton points out, however, ‘innovation comes from novel combinations, the basis of which are serendipity and chance encounters’. It is random creativity. We are finding out that a call or meeting on Zoom or a similar system is not the same as an in-person conversation or brainstorming session. Something is lacking (although time and journeys are being saved). Some companies believe that this lack of physical contact can be redressed by organising regular events for employees.

It is true that a great deal of creativity in design and data can be and is already being achieved online between investigators who are scattered throughout the world. And this problem of remote creativity exists not only for Silicon Valley –a unique ecosystem but one that was already decentralising– but also for smaller versions, whether in Berlin, Paris, London or Barcelona. There are also striking differences in Europe. In Finland, according to a Eurofound study in April, almost 60% are now engaged in teleworking; in Spain, ranked amongst the lowest, the figure is slightly more than 30%.

When working from home started to take off some years ago, Yahoo packed off many of its employees to work remotely. But in 2013, noticing a fall in technological creativity with teleworking, it told them to return. Since 2017 IBM has insisted on working ‘shoulder to shoulder’. Apple –highly focused on the design and innovation of hardware of a kind that cannot easily be done remotely and famous for its secrecy– wants to reopen its famous headquarters in Cupertino as soon as possible.

Big Tech company offices are, or were, characterised by very special working environments, with an authentic campus feel, from the cafés to the shuttles used for getting around, the team games and the large-scale conferences. It is, or was, a way of forging a culture, an identity and a sense of belonging, as well as team working and creativity.

Nobody knows when or how these centres are going to reopen, in a new normality that will be, at least during what could be a transformational period, largely hybrid in nature. But as Sarah Frier in Bloomberg Businessweek has reported, many of those who have switched to working at home in the area in and around San Francisco, with the most expensive housing in the US, are now wondering if they could not live in places further away where rents are lower and spend less time on commuting. But if employees can pay less rent, will their salaries be reduced pro rata? The noises from Mark Zuckerberg point in this direction.

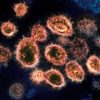

Perhaps the concentration of talent and money in Silicon Valley will dwindle with this remote style of working. Because why would it matter being there as opposed to working for such companies from Essex, Nantes or Oxford –or from Africa– with lower salaries than in San Francisco? These trends are good for the democratisation of financing and technology, as Christian García Almenar, a young Spanish entrepreneur working there, argues. The coronavirus may lead to a much more decentralised Silicon Valley. It would be a cultural shift. The consolidation of this new model also depends on the vaccines and treatments for COVID-19, which could reverse some of the trends leading factories to return to their countries of origin, often robotised, and employees to leave their offices. In any case, many of these companies, some of them vast, have grown even more in their scope, activities and share value, with the consequences and the change in personal and professional lifestyles that this pandemic has wrought. Decentralisation and centralisation.