Collective assets –such things as a clean environment, security, public health and the regulation of traffic on the roads– face a quandary that has been well studied by political science and economics: though everyone, or a vast majority at least, enjoy their benefits, their maintenance requires an individual expenditure, whether economic via taxes or behavioural in terms of complying with norms that would not invariably constitute an individual’s first choice. In the absence of a minimal degree of individual commitment from the majority, the collective asset founders and disappears. If the majority of drivers ignored traffic lights, if the majority of individuals failed to pay taxes, if nobody bothered to take their domestic waste to the nearest collection point or if the majority gave free rein to their instincts when reacting to people who annoy them, we would not enjoy security or orderly traffic or public health and hygiene. But there are always ‘free-riders’ who assume that others will abide by the rules while they enjoy the fruits of such collective assets for free.

“The proposal [from the Netherlands of a mini-Schengen] seems still-born before it has been formalised, because such a group would have to share the same policy vis-à-vis refugees”

Schengen is the main collective asset that the EU has produced, along with the euro and the common market. This is not only objectively but also symbolically the case. Surveys show that Schengen and the euro are the two elements that the European public rate as the EU’s most valuable achievements, the ones that generate most support for the European project. Schengen is currently in jeopardy, however, in grave jeopardy of disappearing as far as its land borders are concerned. European leaders such as Juncker, Hollande and Merkel do not tire of reiterating that the danger is real and that the disappearance of Schengen is moreover a threat to the common market and, over the longer term, to the euro.

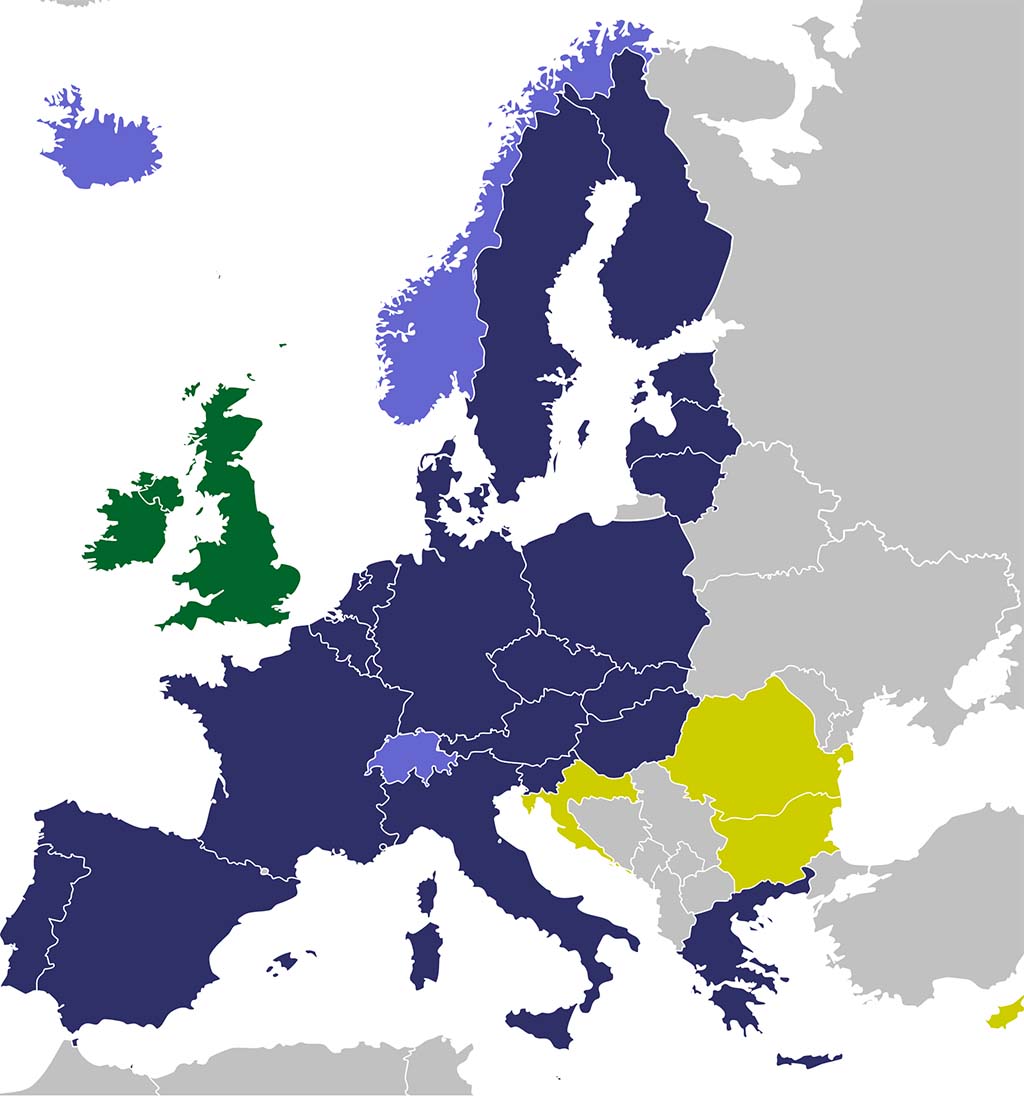

Some months ago, when the first border closures took place in the East in the summer of 2015, the majority of observers thought the closures would trigger a concerted reaction from the EU to prevent the phenomenon from extending. Because, we reasoned, Schengen is too valuable for the EU to allow it to die. What we have seen, however, is that the closing of borders continues to spread and is having a domino effect. It comes as the result of the rise in the number of migrants and refugees that continue arriving and has meant that even Sweden, the country that has traditionally been most generous in granting asylum, has been overwhelmed and has closed its border with Denmark, which, as a result, has closed its border with Germany. Germany, in turn, is controlling inflows through its border with Austria, which is doing the same with Slovenia; while France, stemming from the state of emergency announced in the wake of the November 2015 attacks, has reintroduced controls at all its land and air borders, and Belgium too has suspended the free movement through its frontier with France to prevent the migrants now expelled from the camps in Pas de Calais from entering Belgian territory. Norway, which is a signatory to the Schengen Treaty, has taken matters into its own hands on its southern border. As freedom of movement within the EU went into clear retreat, the Dutch government proposed at the end of 2015 the creation of a mini-Schengen comprising just Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, Belgium and Luxembourg, to which Berlin suggested adding France, a mini-Schengen that would be isolated from the EU’s exterior southern borders. Apart from the fact that the proposal would constitute the final hammer-blow to trust between excluded States and those on the inside, and by extension the EU as a whole, the proposal seems still-born before it has been formalised because the group concerned would have to share the same policy vis-à-vis refugees and France has already stated that it will not accept any more, thereby placing itself in opposition to Merkel, who continues backing an open doors policy.

“The European Commission calculated in January that the restoration of border controls within the Schengen zone had already cost the EU’s economy €3 billion”

Meanwhile, the Commission calculated in January that the restoration of border controls within the Schengen zone had already cost the EU’s economy €3 billion, primarily due to the slowdown in road-borne international trade. But much more important than this figure is the risk that Germany will eventually apply such controls to all its borders, with a post-Merkel government determined to prevent an increase in the arrival of refugees –a political scenario that gains credibility in the context of the data emerging from German opinion polls–.

The recent extraordinary European Council meeting should have produced a response to this crisis, alongside the offer to the UK to avert Brexit, but while it made progress on the latter, it made no headway whatsoever on the former. Observers were left open-mouthed at the lack of reaction from the majority of States: they are not honouring what they agreed to. They are not sending the experts needed to ensure the functioning of the hotspots in Italy and Greece, without which the reception, registration, distribution and return mechanism is impossible, nor are they sending personnel and resources to Frontex, nor are they contributing the funds they promised to Turkey; rather, they erect all possible obstacles to prevent the acceptance of refugee quotas. Many seem to believe they can emerge from the crisis behaving like free-riders: in other words, hoping it will be others contributing to the solution.

It is paradoxical that it is precisely the countries of the East –those that have most benefitted from freedom of movement within the EU and the resulting high number of economic migrants that have gone to the West– that are doing least to sustain Schengen. At the Council meeting they fought to limit the restrictions that the UK wanted to impose on EU migrants’ social rights in the UK, and to a large extent they were successful. With their ‘No to everything’ stance on the refugee crisis, however, they have opened a wide rift and they are rendering a united European solution impossible. The countries that formerly belonged to the Soviet bloc never experienced immigration on a large scale, never took in refugees and have never lived with a population of Muslims; they have a highly negative perception of the latter, which means their citizens are extremely resistant to accepting asylum-seekers from Arab countries. In this aspect of political culture, as in certain others, post-communist Europe clearly differs from Western Europe. Even their limited experience of political asylum in the recent past (the Poles who left their homeland in the 1980s) reinforces their scepticism: most of them used the refuge they found in the West, above all in Germany, as a path to economic betterment, while those that opposed the authoritarian regime stayed behind and mobilised themselves. This is why many of them now see the current wave of immigration as fraudulent.

But the East is not the only problem. Juncker has frequently expressed his anger at the slowness with which the States in general are responding to their duties and commitments. What else is needed to make them react? Possibly that the worst case scenario starts to materialise, with Germany too signing up to this ‘all against all’ approach and restoring border controls. It is a truism to say that the EU only makes progress when it is hit by crises. In this case, how much worse does the crisis need to get?