Without it, nothing makes sense, and it has now emerged into broad daylight following the execution of the Shiite cleric Nimr al-Nimr alongside 46 other prisoners –43 of them convicted of al-Qaeda terrorist activities– and the subsequent riots and assault and torching of the Saudi Embassy in Tehran. The result has been Riyadh breaking off diplomatic relations with Iran, with other Gulf countries, such as Bahrain and the UAE, and even Sudan and Somalia following suit, and the condemnation of the Arab ministers convened at a meeting at Cairo last Sunday. The diplomatic crisis thus created can become a serious setback to Barack Obama’s strategy against Daesh, the Islamic State, to the Tehran regime’s aim of ending its international isolation following the agreement on the limitation and transparency of its nuclear programme and to the prospects for peace in Syria and Yemen.

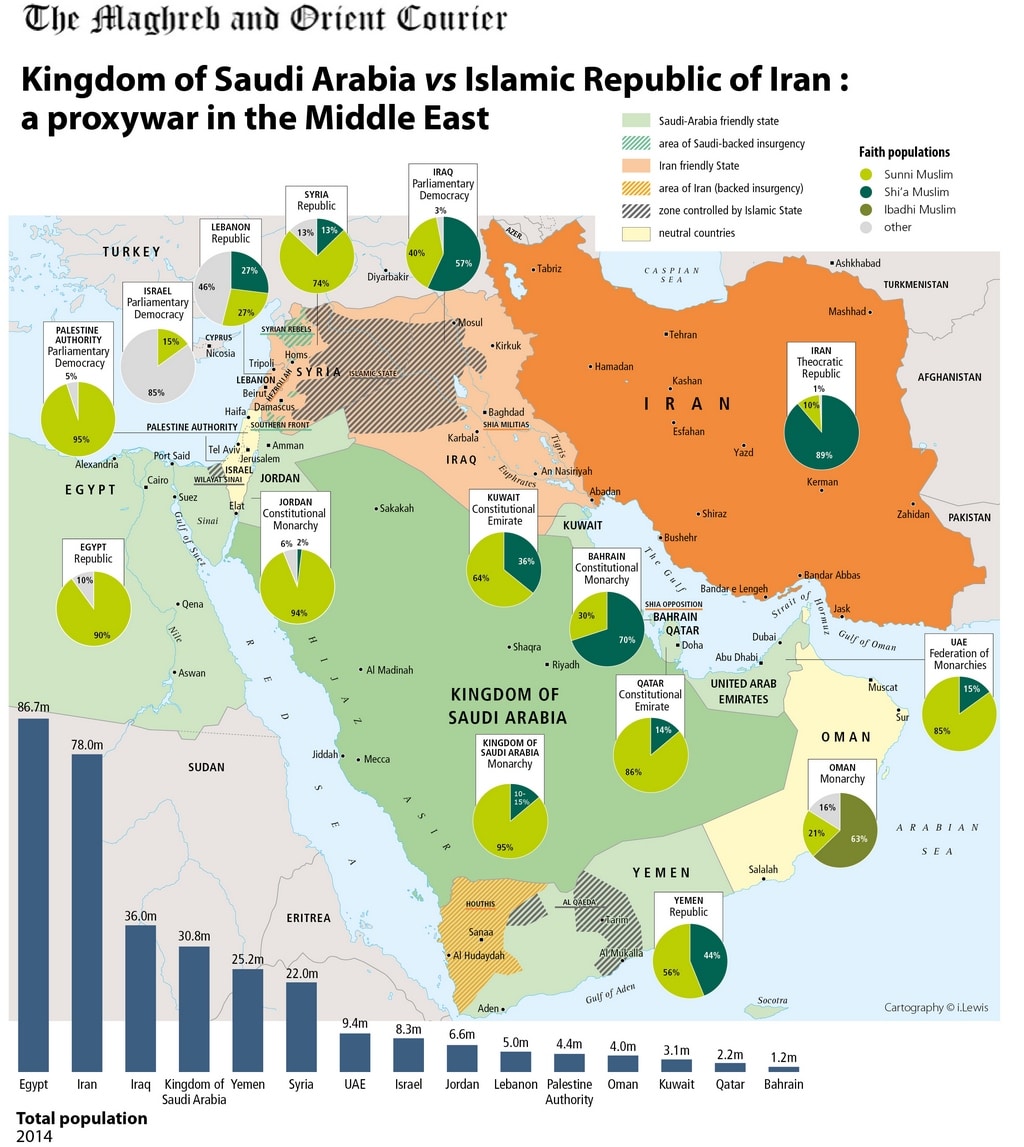

It is a clash between two regional superpowers (although Saudi Arabia has a population of 30 million to Iran’s 80 million) that are both theocracies and are the source of the greatest geopolitical rivalry in the region, exceeding even the confrontation with Israel. The contest is largely played out directly or indirectly through proxies, as shown in an excellent map by Emmanuel Pène, and has religious roots (Sunnis against Shiites, dating back to the 7th century). Nevertheless, before the advent of Islam, which emerged in what is today Saudi soil, Iran –in the form of Persia– had already thousands of years of historical splendour behind it. And the weight of history and of long-standing interests in this confrontation is enormous.

In this respect, Saudi Arabia is doing nothing at random. It has seen how since Saddam Hussein’s overthrow by the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, which gave power to the Shiite majority, Iran has been gaining influence in the region. The first message of al-Nimr’s execution is a warning that the Saudi regime will not tolerate Iranian influence on its own Shia minority or on Shiites in its Arab neighbours (they are a majority in Sunni-dominated Bahrain). Al-Nimr, according to a US diplomatic cable leaked by Wikileaks, ‘eagerly attempted to divorce himself from the image of being an Iranian agent’.

The second message is that Iran must be isolated, and precisely at a time when the Western powers are lifting sanctions against Tehran and preparing to incorporate it to the negotiations in Switzerland on the future of Syria, where the Iranians (friends of the Bashar al-Assad regime) and the Saudis (its enemies) are also at loggerheads. Riyadh feels isolated and partly abandoned by the US.

For Iran, the Sunni terrorist movement Daesh –that emerged from the 2003 invasion and destruction of Iraq’s state structures– is an enemy, and although not a participant in the international coalition, it is fighting it in Syria and Iraq. The Saudis also consider it a great danger, especially since Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the self-proclaimed Caliph of the Islamic State, called for toppling the Saud regime, accusing it of secretly colluding with Israel. But the Arab alliance against Daesh, a movement itself inspired by Saudi Salafism, has not worked. It has even been reported that in September 2014 a Saudi pilot refused to bomb positions held by Daesh on the grounds that he did not wish to attack ‘his brothers’.

But above all, the regime in Saudi Arabia, based on power sharing between the House of Saud and Wahhabi religious leaders, has entered into a transition process of uncertain outcome. The West prefers a lesser evil to other more radical options that might emerge. Some, like Ray Takeyh, consider the tougher stance of the new King, Salman, a sign of weakness. His predecessor, King Abdullah, had been far more cautious in his dealings with Iran. The execution of al-Qaeda fighters after months in prison may also reflect Salman’s concern about his kingdom’s internal destabilisation. To this must be added the effects of the fall in oil prices, the most powerful Saudi weapon against Iran (which, nevertheless, can regain markets as sanctions are lifted) but which also results in a significant drop in revenues. Wielding this weapon has led the Saudi regime to have to announce major cuts in public expenditure, in health, housing and education subsidies and in cheap fuel, all essential to an increasingly frustrated youth. But being tough on Iran is, nevertheless, popular amongst the population.

Saudi Arabia is the source of many problems related to radical Islam, but it is also essential in the fight against Jihadism. The Iran of the ayatollahs is also a source of trouble, but it is now attempting to forge a better international image, more in line with the way its own society is actually evolving. Its Foreign Affairs Minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, has said that Riyadh can ‘continue supporting extremists and promoting sectarian hatred; or it can opt to play a constructive role in promoting regional stability’.

A war between Iran and Saudi Arabia is unlikely. But this new cycle of confrontation could be catastrophic for the region. To reconcile the two sides is increasingly necessary, but at the same time becoming increasingly difficult. The EU, like the US, is loath to be forced to choose, but is not being too successful. Perhaps that is not even the question and what is needed is to introduce a higher degree of governance in a region that is being torn apart by Saudi-Iranian rivalry, as noted by Frederic Wehrey in The Atlantic.

Riyadh had already broken the truce in Yemen by resuming its bombing runs against the Houthis, who are close to Iran (while Tehran has claimed that its embassy in Sana’a has been bombed). Forging a highly complex solution for Syria also seems to be slipping through everyone’s hands, while Saudi-Iranian rivalry can further aggravate tensions in countries such as the Lebanon. At any event, this is all part of a process of Middle-Eastern restructuring, of destroying the old order established by the colonial powers a century ago, a situation that will take neither months nor even years, but decades, to be sorted out. Strategic patience and vision are both of the essence.