The protests in Iran that began in September following the death of Mahsa Amini are intrinsically linked to the defence of women’s rights. However, these protests also stand out because they have led to a change, or rather an exception, in the US sanctions programme against Iran, which is both disruptive and unusual. Specifically, the US Treasury Department has updated a licence that enables export controls on technology products from US companies to Iran for the provision of Internet services, social media platforming, video conferencing and cloud services, and to support anti-censorship tools and software.

Internet shutdowns and the effect on security and rights

The reason: government authorities have increased Internet traffic shutdowns within the country, and content blocking on social media such as Instagram and WhatsApp has risen. These spaces have been widely used for mobilisation and to share protest footage. The phenomenon is not new: during the Iranian economic protests of November 2019, people faced issues when trying to access services such as online payments.

According to AccessNow, Iran was the third country in the world in terms of the largest amount of government-backed Internet shutdowns during 2021, only behind India (106 blockades) and Myanmar (15). Iran carried out five. Trends show that these shutdowns take place during election days or protests.

Many of the countries conducting Internet shutdowns do not have a solid domestic technology industry. However, some do have public Certificate Authorities (CAs) that manage Internet governance certifications, enabling greater self-management and centralised decision-making to redirect Internet traffic. Other widely used tools are ‘deep pocket inspection’ technologies, which allow them to monitor, redirect and alter Internet traffic. This is the case of the National Information Network Project in Iran.

Vis-à-vis the soaring number of Internet and social media blockades, protesters have searched for alternative platforms. Telegram cannot be used, as it was blocked in 2018. Some companies, for example from Canada, have provided access to their messaging services. During some protests in January 2018, the use of one Canadian application increased from 3 million to 10 million users in a few days.

Other technological tools have been supported through funding from US government development programmes, such as NERD (Near East Regional Democracy), funded by the State Department and aimed at promoting democracy and human rights in Iran. It includes targeted training for Iranian activists on Internet freedoms, among other issues.

The role of Iran sanctions and the technology case

However, these two measures –the search for alternative platforms provided by the private sector and government-backed funding through development programmes– are not enough to address security and rights.

The Biden Administration has implemented a licence that provides sanctions exemptions to export technology products to Iran. The goal is to support private sector and civil society needs. It is not a new licence, as a first targeted licence along these lines had previously been launched in 2013. However, the latter only allowed six types of activities (instant messaging, chat and email; social networking; photo and video sharing; web browsing; and blogging) and it had a requirement on the ‘need to enable communications’. This first license was criticised for providing little legal certainty, which reduced incentives to export technologies to Iran in recent years.

In 2022 the updated license has expanded the number of types of services that US players can bring to Iran, and does not require any justification of ‘need’. In addition, the US Treasury Department has opened up the possibility of granting applications that ‘support Internet freedom in Iran, including the development and support of anti-surveillance software by Iranian developers’ special licences that can be issued with greater flexibility. The exception to economic sanctions on Iran applies mostly to software and, to a lesser extent, hardware –which may hinder the export of physical products, such as Elon Musk’s bid to provide Internet services through StarLink microsatellites–.

The effects on global geopolitics

It may seem that the exception to economic sanctions on Iran is somewhat unique. However, the exception proves the incremental role that technology is taking at the geopolitical level, both in its security and economic and human rights implications.

The shift within a sanctions programme that seemed so compact and non-porous to exceptions is unheard of. It is likely that the move is part of President Joe Biden’s strategy of returning to a pact on the nuclear programme that was rejected by Donald Trump in 2015. The current US Administration seeks to revive it.

On the other hand, blocking the Internet is not a loophole in international (soft) law. According to Article 35 of the Constitution of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the UN agency that has also been an area of rivalry over the past year, state that parties have the right to ‘suspend telecommunications services’, as long as this is ‘immediately’ notified to other ITU state parties and the Secretary-General. In the current case of the protests in Iran, the ITU has not been informed.

Finally, this case raises the need to expand the actions on technological diplomacy. In the EU, an awareness-raising campaign on the impact of Internet shutdowns on human rights has recently been finalised between the European External Action Service and the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR). The EU Action Plan on Human Rights and Democracy 2020-2024 includes more than 10 measures on technology policy. And the recently released EU Council Conclusions on Digital Diplomacy in July 2022 prove the commitment to engage with security and rights implications of technology at the global level. Also, the recent appointment of the Ambassador-at-Large of the US State Department’s Bureau of Cyberspace and Digital Policy may allow a greater traction on activities in this regard, building on the Declaration on the Future of the Internet. The EU-US Trade and Technology Council Working Group 6 on misuse that threatens security and human rights needs to speed up its work.

This is not a simple task. Turning political statements, declarations and campaigns into solid, actionable diplomatic initiatives, coalition-building with third countries for decision making and policy agenda setting, and operational cooperation on technological matters are not only necessary measures but also strategic actions to lead the new layer of global power.

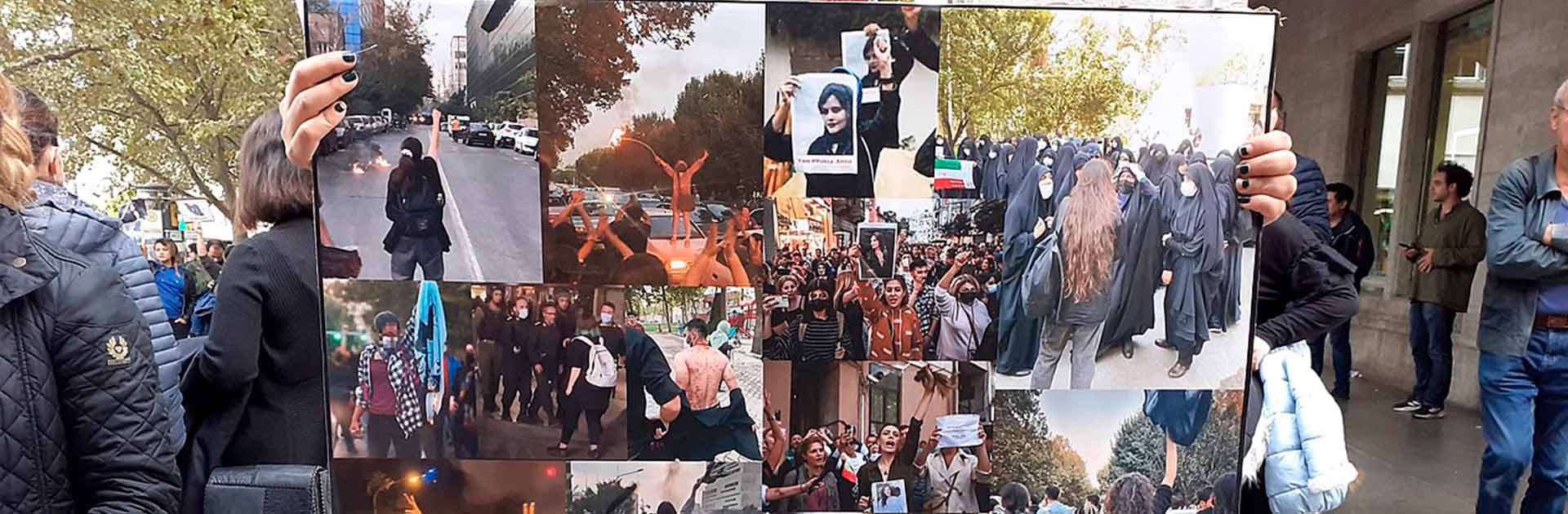

Image: Protests in Stuttgart (Germany) in support of women’s rights following the death of Masha Amini. Photo: Ideophagous (Wikimedia Commons).